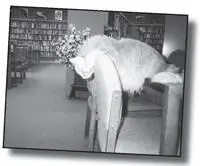

Gary Roma was traveling the country, from the East Coast to North Dakota, to create a documentary about library cats. He arrived expecting the kind of footage he’d shot at other libraries: cats darting apprehensively behind bookshelves, walking away, sleeping, and doing everything possible to avoid looking into the camera. Dewey was exactly the opposite. He didn’t ham it up, but he went about all his usual activities, and he performed them on command. Gary arrived early in the morning to catch Dewey waiting for me at the front door. He shot Dewey sitting by the sensor posts greeting patrons; lying in his Buddha pose; playing with his favorite toys, Marty Mouse and the red yarn; sitting on a patron’s shoulder in the Dewey Carry; and sleeping in a box.

Gary said, “This is the best footage I’ve shot so far. If you don’t mind, I’ll come back after lunch.”

After lunch I sat down for an interview. After a few introductory questions, Gary asked, “What is the meaning of Dewey?”

I told him, “Dewey’s great for the library. He relieves stress. He makes it feel like home. People love him, especially children.”

“Yes, but what’s the deeper meaning?”

“There is no deeper meaning. Everyone enjoys spending time with Dewey. He makes us happy. He’s one of us. What more to life is there than that?”

He kept pressing for meaning, meaning, meaning. Gary’s first film was Off the Floor & Off the Wall: A Doorstop Documentary , and I could imagine him pressing all his subjects: “What does your doorstop mean to you?”

“It keeps the door from hitting the wall.”

“Yes, but what about the deeper meaning?”

“Well, I can use it to hold the door open.”

“Go deeper.”

“Umm, it keeps the room drafty?”

Gary must have gotten deeper meaning out of doorstops because one review mentions linguists dissecting the etymology of the word and philosophers musing about a world without doors.

About six months after filming, in the winter of 1997, we threw a party for the inaugural showing of Puss in Books . The library was packed. The film started with a distant shot of Dewey sitting on the floor of the Spencer library waving his tail slowly back and forth. As the camera zoomed in and followed him under a table, across some shelves, and finally to his favorite cart for a ride, you heard my voice in the background: “We arrived at work one morning, and we went back to open the book drop and empty the books out, and there inside was this tiny little kitten. He was buried under tons of books, the book drop was just full of books. People will come in, and they’ll hear the story of how we acquired Dewey, and they’ll say, ‘Oh, you poor little thing. You were thrown into that book drop on that day.’ And I’ll say, ‘Poor little thing, my foot. That was the luckiest day of that boy’s life, because he’s king around here, and he knows it.’”

As the last words rolled out, Dewey stared right into the camera, and boy, could you tell I was right. He really was the king.

By this time, I was used to strange calls about Dewey. The library was getting a couple requests a week for interviews, and articles about our famous cat were turning up in our mail on an almost weekly basis. Dewey’s official photograph, the one taken by Rick Krebsbach just after Jodi left Spencer, had appeared in magazines, newsletters, books, and newspapers from Minneapolis, Minnesota, to Jerusalem, Israel. It even appeared in a cat calendar; Dewey was Mr. January. But even I was surprised to receive a phone call from the Iowa office of a national pet food company.

“We’ve been watching Dewey,” they said, “and we’re impressed.” Who wouldn’t be? “He seems like an extraordinary cat. And obviously people love him.” You don’t say! “We’d like to use him in a print advertising campaign. We can’t offer money, but we will provide free cat food for life.”

I have to admit, I was tempted. Dewey was a finicky eater, and we were indulgent parents. We were throwing out dishes full of food every day just because he didn’t like the smell, and we were donating a hundred cans of out-of-favor cat food a year. Since the Feed the Kitty campaign of loose change and soda cans didn’t cover the costs and I had vowed to never use a penny of city funds for Dewey’s care, most of that money was coming out of my pocket. I was personally subsidizing the feeding of a good portion of the cats in Spencer.

“I’ll talk to the library board.”

“We’ll send over samples.”

By the time the next library board meeting rolled around, the decision had already been made. Not by me or the board, but by Dewey himself. Mr. Finicky completely rejected the free samples.

Are you kidding me? he told me with a disdainful sniff. I can’t shill for this junk.

“I’m sorry,” I told the manufacturer. “Dewey only eats Fancy Feast.”

Chapter 19

The World’s Worst Eater

Dewey’s pickiness wasn’t just a matter of personality. He had a disease. No, really, it’s true. As far as digestive systems were concerned, that cat really got a lemon.

Dewey always hated being petted on the stomach. Stroke his back, scratch his ears, even pull his tail and poke him in the eye, but never pet his stomach. I didn’t think much of it until Dr. Esterly tried to clean his anal glands when he was about two years old. “I just push down on the glands and squeeze them clean,” he explained. “It will take thirty seconds.”

Sounded easy enough. I held Dewey while Dr. Esterly prepared his equipment, which consisted of a pair of gloves and a paper towel. “Nothing to it, Dewey,” I whispered. “It will be over before you know it.”

But as soon as Dr. Esterly pressed down, Dewey screamed. This wasn’t a mild complaint. This was a full-fledged, terrified cry that ripped out from the base of his stomach. His body bolted like it had been hit by lightning, and his legs scrambled frantically. Then he threw his mouth over my finger and bit down. Hard.

Dr. Esterly looked at my finger. “He shouldn’t have done that.”

I rubbed the sore. “It’s not a problem.”

“Yes, it is a problem. A cat shouldn’t bite like that.”

I wasn’t worried. That wasn’t Dewey. I knew Dewey; he wasn’t a biter. And I could still see the panic in the poor cat’s eyes. He wasn’t looking at anything. He was just staring. The pain had been blinding.

After that, Dewey hated Dr. Esterly. He even hated the thought of getting in the car because it might lead to Dr. Esterly. As soon as we pulled into the veterinary office’s parking lot, he started shaking. The smell of the lobby sent him into uncontrollable tremors. He would bury his head in the crook of my arm as if to say, Protect me.

As soon as he heard Dr. Esterly’s voice, Dewey growled. Many cats hate the veterinarian in his office but treat him as any other human in the outside world. Not Dewey. He feared Dr. Esterly unconditionally. If he heard his voice in the library, Dewey growled and sprinted to the other side of the room. If Dr. Esterly managed to sneak up on him and reached out to pet him, Dewey sprang up, looked around in panic, and bolted away. I think he recognized Dr. Esterly’s smell. That hand, to Dewey, was the hand of death. He had found his archenemy, and it happened to be one of the nicest men in town.

A few uneventful years went by after the anal gland incident, but Dewey eventually went back to prowling for rubber bands. As a kitten, his rubber band hunting had been halfhearted, and he was easily distracted. At about five years of age, Dewey became serious. I started finding the sticky remnants on the floor almost every morning. His litter box was filled not only with rubber worms but with the occasional drop of blood. Sometimes Dewey came tearing out of the back room like someone had lit a firecracker under his rear end.

Читать дальше