Eventually someone always said, “Let’s play ‘Johnny M’Go.’”

Mom and Dad collected antiques, and a few years earlier we’d used them to form the Jipson family band. I played bass, which was a washtub with a broom handle attached to the top and a string running between them. My sister played the washboard. Dad and Jodi banged out a rhythm with a couple of spoons. Mike blew on a comb covered with wax paper. Doug blew across the mouth of a moonshine jar. It was an antique jar, of course, never used for its intended purpose. Mom turned an old pioneer-era wooden butter churn upside down and played it like a drum. Our song was “Johnny B. Goode” When she was little, Jodi always said, “Play ‘Johnny M’Go’!” The name stuck. Every year we played “Johnny M’Go” and other old rock-and-roll songs deep into the night on our homemade instruments, a homage to a country tradition that probably never existed in this part of Iowa, laughing with one another the whole time.

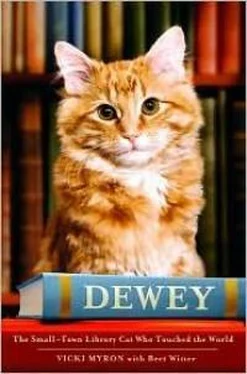

After Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve, Jodi and I headed home to Dewey, who as always was eager to see us. We spent Christmas morning together in Spencer, just the three of us. I hadn’t even gotten Dewey a present. What would be the point? He already had more stuff than he needed. And after a year together, our relationship had gone well beyond token gifts and forced attention. We didn’t have anything to prove. All Dewey wanted or expected from me was a few hours a day of my time. I felt the same way. That afternoon I dropped Jodi at Mom and Dad’s house and slipped home to spend time with Dewey on the couch, doing nothing, saying nothing, just two friends lounging around like a couple of old socks waiting for a shoe.

Chapter 13

A Great Library

A great library doesn’t have to be big or beautiful. It doesn’t have to have the best facilities or the most efficient staff or the most users. A great library provides. It is enmeshed in the life of a community in a way that makes it indispensable. A great library is one nobody notices because it is always there, and it always has what people need.

The Spencer Public Library was founded in 1883 in Mrs. H. C. Crary’s parlor. In 1890, the library moved to a small frame building on Grand Avenue. In 1902, Andrew Carnegie granted the town $10,000 for a new library. Carnegie was a product of the industrial revolution that had turned a nation of farmers into factory workers, oilmen, and iron smelters. He was a ruthless corporate capitalist who built his United States Steel into the nation’s most successful business. He was also a Baptist, and by 1902 he was deep into the pursuit of giving away his money to worthwhile causes. One cause was providing grants to small towns for libraries. For a town like Spencer, a Carnegie library was a sign you had made it not exactly to the top, but farther than Hartley and Everly.

The Spencer Public Library opened on March 6, 1905, on East Third Street, half a block off Grand Avenue. It was typical of Carnegie libraries, since Carnegie had mandated a classical style and symmetry of design. There were three stained-glass windows in the entrance hall, two with flowers and one with the word library . The librarian perched behind a large central desk, surrounded by drawers of cards. The side rooms were small and cloistered, with bookshelves to the ceiling. In an era when public buildings were segregated by sex, men and women were free to enter any room. Carnegie libraries were also among the first to let patrons choose books off the shelves instead of making requests to the librarian.

Some historians describe Carnegie libraries as plain, but that is true only in comparison to the elaborate central libraries of cities like New York and Chicago, which had carved friezes, ornately painted ceilings, and crystal chandeliers. Compared to the parlor of a local woman’s home or a storefront on Grand Avenue, the Spencer Carnegie library was impossibly ornate. The ceiling was high, the windows enormous. The half-underground bottom floor held the children’s library, an innovation at a time when children were often kept locked away in their homes. Children could sit and read on a circular bench, while above them a window looked out at ground level on a flat grass lawn. The floorboards throughout the building were dark wood, highly polished and very wide. They creaked when you walked, and often that creaking was the only sound you could hear. The Carnegie was a library where books were seen, not heard. It was a museum. It was as quiet as a church. Or a monastery. It was a shrine to learning, and in 1902 learning meant books.

When many people think of a library, they think of a Carnegie library. These are the libraries of our childhood. The quiet. The high ceilings. The central library desk, complete with matronly librarian (at least in our memories). These libraries seemed designed to make children believe you could get lost in them, and nobody could ever find you, and it would be the most wonderful thing.

By the time I was hired in 1982, the old Carnegie library was gone. It had been beautiful but small. Too small for a growing town. The land deed specified the town must use it for a library or return it to the owner, so in 1971 the town tore down the old Carnegie building to build a bigger, more modern, more efficient library, one without squeaky floorboards, dim lighting, imposingly high bookshelves, and rooms to get lost in.

It was a disaster.

Spencer is built in a traditional style. The retail buildings are brick, the houses along Third Street two- and three-story frame boardinghouses. The new library was concrete. One story tall, it hunched on the corner like a bunker. Its original wide lawn was gone, replaced by two tiny gardens. Too shadowed to grow much, they were soon filled in with rocks. The glass front doors were set back from the street, but the entryway was enclosed and unwelcoming. The east wall, which faced the town middle school, was solid concrete. Grace Renzig lobbied herself onto the library board in the late 1970s with the goal of having vines planted along the east wall. She got her vines a few years later, but she ended up staying on the board for almost twenty years.

The new Spencer Public Library was modern, but with a brutish efficiency. And it was flat-out cold. A glass wall faced north, with a lovely view of the alley. In the winter, you couldn’t keep the back of the library warm. The floor plan was open, leaving no space for storage. There was no designated staff area. There were only five electric outlets. The furniture, made by local craftsmen, was beautiful but impractical. The tables had prominent support bars so you couldn’t pull up additional chairs, and they were solid oak with black laminate tops, so they were too heavy to move. The carpet was orange, a Halloween nightmare.

Or to put it more simply, the building wasn’t right for a town like Spencer. The library had always been well run. The collection of books was exceptional, especially for a town the size of Spencer, and the directors had always been early adopters of new technologies and ideas. For enthusiasm, professionalism, and expertise, the library was top-notch. But after 1971, it was all squeezed into the wrong building. The exterior didn’t fit the surrounding area. The interior wasn’t practical or friendly. It didn’t make you want to sit down and relax. It was cold in every sense of the word.

We started the remodel—let’s call it the warming process—in May 1989, just as northwest Iowa was waking up and changing from brown to green. The lawns suddenly needed mowing, the trees on Grand Avenue were throwing out new leaves. On the farms, the plants were pushing through the soil and unfolding, and you could finally see the result of all that time spent fixing equipment, churning fields, and planting seeds. The weather turned warm. The kids brought out bicycles. At the library, after almost a year of planning, it was finally time to work.

Читать дальше