On a summer day about a year after his grand new life started, Duc went outside and Vierig’s wife saw him collapse. She yelled to Vierig, who ran out and found Duc unresponsive. He scooped the dog up and brought him inside the “Duc Room,” a special room they had converted for Duc’s comfort. Vierig sat down cross-legged on the floor, supporting Duc’s head and upper body in his arms. He stroked his old face and neck, trying to figure out what was wrong. Suddenly Duc howled like a wolf, a plaintive cry Vierig had never heard before. Duc took one last breath and died in Vierig’s arms.

Overcome by the sudden loss, and that primal howl, Vierig held his dog, telling him how much he loved him, how much Duc meant to him. Eventually he covered Duc with a brand-new 4-by-6-foot Marine Corps flag. He lay it over Duc’s body. “He had done so much for me, I wanted to do right by him.”

Within moments, four dogs Vierig was training for police and private companies entered the room. They were all energetic working dogs—a golden retriever, two Malinois, and a German shepherd. They’d revered Duc in life. They would run around and nip and chase and tackle one another, but they would leave him in peace. Now the dogs—every one of them—lay down quietly in a semicircle next to Duc’s flag-draped body. They were not sleeping, but lying attentively, calmly. They stayed like this for twenty minutes. These independent-natured dogs never would lie next to each other—much less Duc—like this.

“They were paying respects to a dog who was deeply respected. That’s not anthropomorphism,” Vierig says. “If you’d seen it, you’d know.”

Vierig wanted Duc’s grave to be near the river, where fishermen walk by, so others would remember his friend, even if they had never met him. He wanted them to know that here lay a great dog. He dug a deep grave in a tree-filled area across the river and came back for Duc. Vierig wrapped Duc’s body in the marine flag, picked up the ninety-pound dog, and hoisted him across the back of his shoulders. He walked him out his backyard and crossed the chest-deep water of the Weber, making sure to keep Duc dry. He lay Duc on the ground under a big tree with lots of shade.

Then he placed Duc in the grave, buried him, and covered the site with big round stones from the riverbed to help keep other animals from digging down. Earlier in the day he had attached to the tree Duc’s old military kennel sign with his name on it. To this, he attached all of Duc’s medals and ribbons. There were about thirteen, but since military working dogs don’t officially rate ribbons and medals, they were actually all Vierig’s, for anything he earned while Duc was his dog.

Vierig has since moved, but he still goes up to visit his dog and replaces ribbons when they wear out.

54

54

WHO NEEDS MEDALS OR STAMPS?

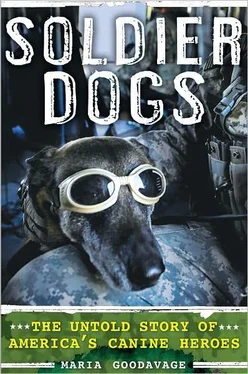

Duc got his ribbons the way many dogs do: unofficially, and because of someone’s great admiration and respect. Dogs in the military are not officially awarded ribbons or medals from the Department of Defense. America’s canine heroes can save all the lives in their squad and get injured in the process, but they will not receive true official recognition.

When you hear about dogs garnering awards and decorations, it’s usually because someone higher up at a command knows how valuable these dogs are and wants to award their valor, their heroism, their steadfast dedication to their mission. And the dogs get the awards, but the awards don’t have the blessing of the Department of Defense. One former army handler I spoke with says he has seen dogs get all kinds of honors, including Meritorious Service Medals and Army Commendation Medals. Some dogs have also received Purple Hearts and Silver Stars. The ceremonies look official. But these are simply “feel-good honors,” says Ron Aiello, president of the national nonprofit organization the United States War Dogs Association.

For the last several years, Aiello and his group, which helps soldier dogs and their handlers, have been among a few organizations trying to get more official recognition of military working dogs. So far, the Department of Defense hasn’t budged.

Aiello’s group has been told medals and awards are only for human troops, not animals. Aiello is sensitive to the fact that giving a dog the same award as a person might be a touchy subject for some. So he proposed a special service medal just for dogs. That didn’t work, either. Finally, “because the DOD had no interest in awarding our military working dogs for their service,” explains Aiello, the group simply asked for official sanction of the organization in issuing the United States Military Working Dog Service Award. You can guess the result.

Because he and his team knew how much it meant for handlers to have some recognition for their dogs, they went ahead and created the United States Military Working Dog Service Award anyway. It can be bestowed on any dog who has actively participated in ground or surface combat. It’s a large bronze-colored medal on a red, white, and blue neck ribbon. It comes with a personalized certificate. There have been about eighty awarded so far, and Aiello says handlers greatly appreciate their dogs being recognized like this.

The move to see dogs get some kind of official recognition is gaining support from those inside, as well. In 2011, Master Chief Scott Thompson, head of military working dog operations in Afghanistan at the time, spoke at a biannual conference at Lackland Air Force Base. He said that these dogs absolutely deserve medals. “Some veterans may say it’s degrading to them, but it shouldn’t be. Most commanders have given dogs Purple Hearts, but it wouldn’t have to be the same awards. I think most people would agree that dogs have earned the right to this. There needs to be some kind of legislation to recognize what dogs do, and we need to do the right thing.”

There was once a German shepherd mix who received an official Distinguished Service Cross, a Purple Heart, and a Silver Star. His name was Chips. He performed many feats of courage and loyalty while serving in World War II, but one event in particular shows what this dog was made of. In the dark of early morning on July 10, 1943, on a beach in Sicily, Chips and his handler, Private John P. Rowell, came under machine-gun fire from a camouflaged pillbox. Here’s how Michael Lemish describes it in his book War Dogs :

Immediately Chips broke loose from Rowell, trailing his leash and running full-steam toward the hut. Moments later, the machine-gun fire stopped and an Italian soldier appeared with Chips slashing and biting his arm and throat. Three soldiers followed with their arms raised in surrender. Rowell called Chips off and took the four Italians prisoner. What actually occurred in the pillbox is known only by the Italians, and, of course, the dog. Chips received a minor scalp wound and displayed powder burns, showing that a vicious fight had taken place inside the hut and that the soldiers had attempted to shoot the dog with a revolver. But the surrender came abruptly, indicating that Chips was solely responsible.

That night, Chips also alerted to ten Italian soldiers moving in on them. Rowell was able to take them all prisoners because of his dog’s warning. Chips was lauded for his heroism and highly decorated. But William Thomas, national commander of the Military Order of the Purple Heart, was not amused. “It decries the high and lofty purpose for which the medal was created.” The War Department rescinded the dog’s awards, and the medals were returned.

Читать дальше

54

54