I was honored to participate in the Women in the World Summit in New York City in 2013. I was on a panel with Phiona Mutesi, a teenage chess champion from Uganda, her coach Robert Katende, and Marisa van der Merwe, who co-founded the Moves for Life chess-in-schools program in South Africa. The life experiences of these two remarkable women could not be more different, but they both speak to the importance and power of education, especially in the developing world.

Phiona came from the slums of Katwe in the Ugandan capital of Kampala, growing up in deprivation and fear that few members of our New York audience could imagine. Her discovery of Robert’s local chess club became a miracle for Phiona, showing her what she could achieve intellectually. More important than how her chess talent has allowed her to travel the world, she now plans to be a doctor. This is the first and most powerful gift education can provide: a self-confidence that transforms a child’s view of his or her potential. Very few kids can truly expect to turn success at football or other physical sports into an education or career. This is also true for chess, but the knowledge that you can compete, succeed, and enjoy yourself on an intellectual level applies to everything you undertake in life.

If there is anything I have learned from my extensive travels all over the world to promote chess in education it is that talent exists everywhere. The question is how to give it the opportunity to express itself and to thrive. This opportunity that education creates is what is lacking in so much of the undeveloped world—and in parts of the developed world as well if we are honest—a shortfall that has wide-ranging and damaging effects. Education is the most effective way to address poverty and violence, even to tackle complex issues of terrorist groups and vicious warlords.

Programs that spend billions on distributing medicine and food to impoverished areas are of course wonderful. Foundations that combat disease and hunger in Africa have saved countless lives. While life may be the most precious gift, it is not enough to play sorcerer only in the morning, to create the sky and not the earth. When you look around the world’s trouble spots you see that when kids don’t have access to education, many of those who are being saved by Western aid are destined for lives of misery and violence.

Do not misunderstand me. This is of course not an argument against providing life-saving drugs or a denunciation of the brilliant and caring people and programs that provide them. But do not turn away as soon as the babies are born and fed. Do not turn away at all. Look at the young boys enslaved by drug gangs and armies of every stripe, at the unemployed young men who find purpose and profit in victimizing their neighbors, at the girls and women who are inevitably the greatest victims of violence.

The only medicine that can cure these plagues is safe and equal access to a classroom. The best proof of the truth of this may come from the other side, from the brutal groups that burn down schools and shoot schoolgirls in cold blood. It’s rare to hear about coordinated attacks on aid that brings medicine and food. These things pose little threat to the Taliban, the regional warlords, or to the corrupt politicians who steal funds that could go to help their people. Religious fanatics, mercenaries, and armies all need healthy recruits, after all.

What these thugs cannot abide is the flourishing of education, with the noteworthy exception of militant religious teaching that often closes minds instead of opening them. They despise the possibility of an educated population, knowing it would mean the end of their kind in a generation. So the Taliban did not just close the schools where fifteen-year-old Malala Yousafzai lived in Swat, Pakistan, they destroyed them. They did not just tell Malala not to go to school, they shot her.

Education in the developing world means far more than keeping at-risk children off the streets. It is the only way to build an economy that can compete in the twenty-first century, as globalization demands. Healthy bodies are not enough as entire populations move from the countryside into cities and as even agriculture becomes a high-tech enterprise. Reading and writing cannot be luxuries at a time when access to the Internet is more prevalent than access to decent plumbing.

Even the most pragmatic know education aid is a good investment. It costs far less to protect and educate children than it does to send in soldiers and cruise missiles to kill them after they have been abandoned and then recruited by thugs into violence and terror. An educated population is less vulnerable to propaganda and more capable of producing the entrepreneurs and leaders who can create economic opportunity.

There are programs that pay opium and cocaine farmers the difference to grow less pernicious crops. It’s cheaper and far less violent than fighting a militarized drug war on the borders and in the streets of our cities. Why not invest the same way in kids? How many schools and supplies could be built for the cost of producing and operating one drone? How many teachers, vocational trainers, and guards could be hired for the cost of one special ops deployment?

The Human Rights Foundation works to aid and unite brave people working for individual liberty and justice around the world. Our annual Oslo Freedom Forum brings together hundreds of dissidents, activists, philanthropists, journalists, and policy makers from all over the world. The goal is for every participant to learn and to share and to return home with new strength and new ideas.

In 2014, I presented our Vaclav Havel Prize for Creative Dissent to Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina of Pussy Riot. It is not often I agree with the Putin regime, but in their case I must make an exception. Their startling performance, their ridicule of Putin, their courage to take a stand with their art, this was not just a cheap prank as their defense lawyer attempted to argue. It was political and it was powerful.

And their trial in Moscow was no trivial persecution. Dictatorships must be feared to survive and so they cannot bear to be mocked. Unlike most observers, Putin, with his dictator’s animal instinct, immediately perceived the seriousness of the threat. The result was two years in prison for a performance that lasted fifteen minutes.

And so my last policy recommendation is to listen to the dissidents, even if you do not like what they have to say. They are the ones who reveal to us the dark realities of our societies, the realities that most of us have the luxury to turn away from. Listen to the dissidents because they warn us of the threats that target minorities first and inevitably spread to the majority. Every society has its dissidents, not just dictatorships. They speak for the disenfranchised, the ignored, and the persecuted. Listen to them now, because they speak of what is to come.

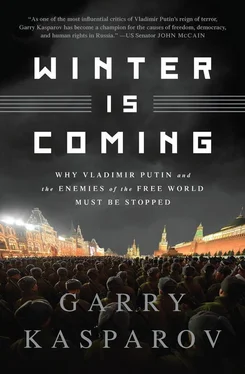

“Winter is coming” is a warning, not an inevitable conclusion. The good thing about the seasons of political and social change is that we can affect them if we try hard enough. If we rouse ourselves from our complacency and relearn how to stand up to the dictators and terrorists who threaten the modern world we have built, we can alter our course. Anti-modernity is a dangerous virus, and to remove a virus a reboot or a reset is not enough. We have to build a values-based system that is robust enough to resist the virus at home, smart enough to stop it before it spreads, and bold enough to eradicate it where it grows.

Whenever I’m at risk of sinking into a sea of interesting ideas and intriguing opportunities, my wife Dasha throws me a line and pulls me to the right destination. She knew that this was the right book at the right time.

Читать дальше