Boris Nemtsov, my longtime friend and colleague in the Russian opposition, was murdered in cold blood in the middle of Moscow on February 27, 2015. Four bullets in the back ended his life in sight of the Kremlin, where he once worked as Boris Yeltsin’s deputy prime minister. Photos from the scene showed a cleaning crew scrubbing his blood off the pavement within hours of the murder, so it is not difficult to imagine the quality of the investigation that followed.

Putin actually started, and ended, the inquiry while Boris’s body was still warm by calling the murder a “provocation,” the term of art for suggesting his enemies are murdering one another in order to bring shame upon his innocent brow. He then brazenly sent a message of condolence to Nemtsov’s mother, who often warned her fearless son that his actions could get him killed in Putin’s Russia.

Hours after Boris’s death, reports said that police were raiding his home and confiscating papers and computers. Putin’s enemies are often victims and his victims are always suspects. Boris was a passionate critic of Putin’s war in Ukraine and was about to finish a report on the presence of Russian soldiers in Donbass, a matter the Kremlin has spared no effort to cover up. But “Did Putin give the order?” rings as hollow today as it did when journalist Anna Politkovskaya was gunned down in 2006 or when MH17 was shot down over Eastern Ukraine last year.

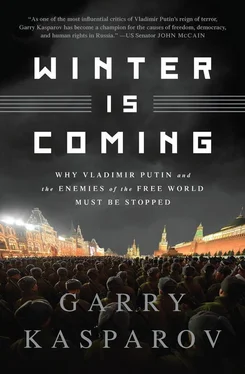

As long as Putin is in office we’ll never know who gave the order, but there is no doubt that he is directly responsible for creating the conditions in which these outrages occur with such terrible frequency. Putin’s early themes of restoring the national pride and structure that were lost with the fall of the USSR have slowly run out of steam and been replaced with a toxic mixture of nationalism, belligerence, and hatred. By 2014, the increasingly depleted opposition movement, long treated with contempt and ridicule, had been rebranded in the Kremlin-dominated media as dangerous fifth columnists, or “national traitors” in the vile language they frequently borrowed from the Nazis.

To match the propaganda, Putin shifted more support to the most repressive, reactionary, and bloodthirsty elements in the regime. Among them are Chechen warlord Ramzan Kadyrov and chief prosecutor Alexander Bastrykin, who recently declared that the Russian constitution was “standing in the way of protecting the state’s interests.” In this environment, blood becomes the coin of the realm, the way to show loyalty to the regime. This is what Putin has wrought in order to keep his grip on power: a culture of death and fear that spans all eleven Russian time zones and is now being exported to Eastern Ukraine.

Boris Nemtsov was a tireless fighter and one of the most skilled critics of the Putin government, a role that was by no means his only possible destiny. A successful mayor in Nizhny Novgorod and a capable cabinet member and parliamentarian, he could have led a comfortable life in the power vertical as a token liberal voice of reform. But Boris was unqualified to work for the Putin regime. He had principles, you see, and could not bear to watch our country descend back into the totalitarian depths.

And so Boris launched his big body, big voice, and big heart into the uphill battle to keep democracy alive in Russia. We worked together after he was kicked out of parliament in 2004 and by 2007 we were close allies in the opposition movement. He was devoted to documenting the crimes and corruption of Putin and his cronies, hoping they would one day face a justice that seemed further away all the time.

Along with a report on Russian soldiers in Ukraine, he had been working hard on the protest march planned for that Sunday in Moscow, a march that became his funeral procession. Boris and I began to quarrel after Putin returned as president in 2012. To me it signaled the end of any realistic hopes that there could be a peaceful political solution to regime change in Russia. But Boris was always hopeful. He would tell me I was too rash, that “you have to live a long time to see change in Russia.” Now he will never see it.

We cannot know exactly what horror will come next, only that there will be another and another as long as Putin remains in power. The only way Putin’s rule will end is if the Russian people and Putin’s elites understand they have no future as long as he is there. Right now, no matter how they really feel about Putin and their lives, they see him as invincible and unmovable. They see him getting his way in Ukraine, taking territory and waging war. They see him talking tough and making deals with Merkel and Hollande. They see his enemies dead in the streets of Moscow.

Statements of condemnation and concern over Boris’s murder quickly poured forth from the same Western leaders who have done so much to appease Putin in recent days, weeks, and years. If they truly wish to honor my fearless friend, they should declare in the strongest terms that Russia will be treated like the criminal rogue regime it is for as long as Putin is in power. Call off the sham negotiations. Sell weapons to Ukraine that will put an unbearable political price on Putin’s aggression. Tell every Russian oligarch that there is no place their money will be safe in the West as long as they serve Putin.

The response so far is not encouraging, a phrase I tire of writing. Many of the habitual statements of concern and condemnation call for Putin to “administer justice,” a plea that could almost could be considered sarcastic. Western media inexplicably continues to give a platform to Putin’s cadre of propagandists without challenging their blatant lies.

We may never know who killed Boris Nemtsov, but we do know that the sooner Putin is gone, the better chance there is that the chaos and violence Boris feared can be avoided. It is a chance Russia and the world must take.

Looking back through history, great changes in the framework between nations have been necessary after a period of great conflict. In 1648, the Peace of Westphalia created the modern age of Europe after the Thirty Years’ War. The War of the Spanish Succession was ended by the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht. In 1815, the Congress of Vienna created a new European map after the defeat of Napoleon’s France. At the Berlin Conference of 1879 the equilibrium was reestablished after the Russo-Turkish War. At the end of the nineteenth century, the general belief was that this balance would lead to a golden era of peace. Utopian and pacifist literature dreamed of a world without borders right up to the beginning of World War I.

After the First World War we had the Versailles Treaty and the creation of the League of Nations. The League was a failure and the unwillingness to accept this fact led to World War II. On March 5, 1946, in Fulton, Missouri, in his renowned “iron curtain” speech, Winston Churchill spoke about the new dangers to freedom, this time from Communism. It is almost forgotten that he also warned how the newly formed United Nations could fail.

Churchill said of the new organization, “We must make sure that its work is fruitful, that it is a reality and not a sham, that it is a force for action, and not merely a frothing of words, that it is a true temple of peace in which the shields of many nations can someday be hung up, and not merely a cockpit in a Tower of Babel.” Unfortunately, Churchill’s prophecies have come to pass and today we are stuck with an outdated organization that was developed after WWII to prevent a nuclear clash between superpowers. The old stalemate diplomacy of the Cold War will not help us against suicide attacks and hybrid war. Instead of an entity that exists to freeze conflicts, we need one that can offer real solutions based on modern values.

Читать дальше