At the beginning of his mandate his main objective was to convince the Francoists and the democratic opposition that the reform he was going to carry out was the only way they would both achieve their conflicting purposes. He assured the Francoists that they’d have to renounce certain elements of Francoism in order to ensure the survival of Francoism; he assured the democratic opposition that they’d have to renounce certain elements of the break with Francoism in order to ensure the break with Francoism. To everyone’s surprise, he convinced them all. First he convinced the Francoists and, when he’d convinced them, he convinced the opposition: he completely deceived the Francoists, but not the opposition, or not entirely, or no more than he deceived himself, but he did as he pleased with them, obliged them to play on the field that he chose and by the rules he devised and, once he’d won the match, put them to work in his service. How did he achieve it? In a certain sense, with the same histrionic methods of seduction with which Emmanuele Bardone persuaded Italians and Germans alike that there was no one in the world more important than them and that he was ready to do anything for their cause, and with the same chameleon-like gifts with which Bardone convinced the Germans that he was a fervent supporter of the Reich and the Italians that he was an undercover adversary of the Reich. If he was almost always unbeatable on television, because he mastered it better than any other politician, face to face he was even better: he could sit down alone with a Falangist, with an Opus Dei technocrat or with a Guerrillero de Cristo Rey and the Falangist, technocrat or paramilitary would say goodbye to him with the certainty that deep down he was a paramilitary, a Falangist or a defender of Opus; he could sit down with a soldier and, remembering his time as a reserve second lieutenant, say: Don’t worry, deep down I’m still a soldier; he could sit with a monarchist and say: I am first and foremost a monarchist; he could sit down with a Christian Democrat and say: In reality, I’ve always been a Christian Democrat; he could sit with a Social Democrat and say: What I am, deep down, is a Social Democrat; he could sit with a Socialist or a Communist and say: I’m no Communist (or Socialist), but I am one of you, because my family was Republican and deep down I’ve never stopped being one. He’d say to the Francoists: Power must be ceded to win legitimacy and conserve power; to the democratic opposition he’d say: I have power and you have legitimacy: we have to understand each other. Everyone heard from Suárez what they needed to hear and everyone came out of those interviews enchanted by his kind-heartedness, his modesty, seriousness and receptiveness, his excellent intentions and his will to convert them into deeds; as for him, he wasn’t yet Prime Minister of a democratic government, but, just as Bardone tried to act the way he thought General Della Rovere would have acted from the moment he entered the prison, from the moment of his appointment as Prime Minister he tried to act the way he thought a prime minister of a democratic government would act: like Bardone, everything he saw and felt helped him to perfect his interpretation; like Bardone, he soon began to steep himself in the political and moral cause of the democratic parties; like Bardone, he deceived with such sincerity that not even he knew he was deceiving.

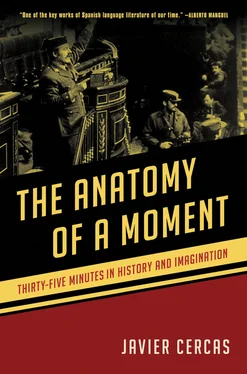

That was how over the course of that short first year in government Suárez constructed the foundations of a democracy out of the materials of a dictatorship by successfully carrying out unusual operations, the most unusual of which — and perhaps the most essential — entailed the liquidation of Francoism at the hands of the Francoists themselves. The idea he owed to Fernández Miranda, but Suárez was much more than simply its executor: he studied it, he got it ready and he put it into practice. It was almost about achieving the squaring of a circle, and in any case reconciling the irreconcilable to eliminate what was dead and seemed alive; at heart it was about a legal ruse based on the following reasoning: Franco’s Spain was ruled by an ensemble of Fundamental Laws that, as the dictator himself had often stressed, were perfect and offered perfect solutions for any eventuality; however, the Fundamental Laws could be perfect only if they could be modified — otherwise they wouldn’t have been perfect, because they wouldn’t have been capable of adapting to any eventuality — the plan conceived by Fernández Miranda and deployed by Suárez consisted of devising a new Fundamental Law, the Law for Political Reform, which would be added to the rest, apparently modifying them though actually repealing them or authorizing them to be repealed, which allowed the change of a dictatorial regime for a democratic regime respecting the legal procedures of the first. The sophistry was brilliant, but needed to be approved by the Francoist Cortes in an unprecedented act of collective immolation; its implementation was vertiginous: by the end of August 1976 a draft of the law was already prepared, at the beginning of September Suárez announced it on television and over the next two months threw himself into battle on all fronts to convince the Francoist representatives to accept their suicide. The strategy he devised to achieve it was a wonder of precision and swindle: while from his position as President of the Cortes Fernández Miranda threw spanners in the works of the law’s detractors, they put in charge of its presentation and defence the nephew of the founder of the Falange and member of the Council of the Kingdom, Miguel Primo de Rivera, who would ask them to vote in favour ‘in memory of Franco’; in the weeks before the plenary session, Suárez, his ministers and top government officials, after dividing up the procuradores , as the Francoist Cortes members were called, opposed to or reluctant to support the project, breakfasted, had aperitifs, lunched and dined with them, flattering them with brimming promises and tangling them in traps for the gullible; only in a few cases did they have to resort to unveiled threats, but with one group of recalcitrant members there was nothing for it but to pack them off on a Caribbean cruise on a junket to Panama. Finally, on 18 November, after three consecutive days of debate during which on more than one occasion it seemed like everything was going to fall through, the Cortes voted on the law; the result was unequivocal: 425 votes in favour, 59 against and 13 abstentions. The reform was approved. The television cameras captured the moment, and it’s since been reproduced on a multitude of occasions. The members of the Francoist Cortes stand and applaud; standing up, Suárez applauds the Francoist procuradores . He looks emotional; he looks like he’s on the verge of tears; there is no reason to think he’s pretending or, like the consummate actor he is, if he is pretending, that he’s not feeling what he’s pretending to feel. The truth is he might as well have been laughing inside and crying his eyes out for the bunch of fools who’ve just signed their own death sentence amid the embraces and congratulations of a tremendous Francoist fiesta.

It was a spectacular sleight of hand, and the greatest success of his life. In Spain the democratic opposition rubbed their eyes; outside Spain the incredulity was total: ‘stunning victory for suárez’, ran the headline in the New York Times ; ‘cortes appointed by dictator have buried francoism’, said Le Monde . A few days later, allowing himself not an instant’s respite or his adversaries any time to recover from their stupor, he called a referendum on the recently approved law; it was held on 15 December and he won it with almost 80 per cent participation and almost 95 per cent of the votes in favour. For the Francoists and for the democratic opposition, who had advocated voting against or abstaining, the setback was conclusive; much more so for the former than for the latter, of course: from that moment on the Francoists could resort only to violence, and the week of 23 to 28 January — in which far-right groups murdered nine people in a pre-war atmosphere and Suárez was certain someone would attempt a coup d’état — was the first notice that they were ready to employ it; as for the democratic opposition, they found themselves obliged to discard the chimera of imposing their outright clean break with Francoism to accept the unexpected and tricky reforming break imposed by Suárez and began to negotiate with him, divided, messed up and weakened, under terms he had chosen and that best suited him. Furthermore, by then, around February 1977, it was already clear to everyone that Suárez was going to fulfil the task the King and Fernández Miranda had entrusted to him in record time; in fact, once the Rubicon of the Law for Political Reform was crossed, Suárez had only to finalize the dismantling of the legal and institutional framework of Francoism and call free elections after agreeing with the political parties the requisites of their legalization and participation in the elections. In theory his job ended there, that in theory was the end of the show, but by then Suárez already believed in his character and was elated, riding the biggest wave of the tsunami of his success, so nothing would have seemed more absurd to him than giving up the position he’d always dreamt of; it may be, however, that this was the King’s and Fernández Miranda’s intention when they gave him the starring role in that drama of seductions, half-truths and deceits, sure as they were perhaps that the charming and smooth nonentity would burn out on stage, sure as they were in any case that he would be incapable of managing the complexities of the state in normal conditions, and even more so after democratic elections: once these were called and his task concluded, Suárez should retire behind the curtain, amid applause and tokens of gratitude, to cede the favour of the spotlight to a real statesman, perhaps Fernández Miranda himself, perhaps the eternally prime ministerial Fraga, perhaps the Deputy Prime Minister Alfonso Osorio, perhaps the cultivated, elegant and aristocratic José María de Areilza. Of course, Suárez could have ignored the King’s intention, forced his hand and stood for election without his consent, but he was the Prime Minister appointed by the King and he wanted to be the King’s candidate and then the King’s Prime Minister-elect, and during those brilliant months, while he gradually freed himself of Fernández Miranda’s tutelage and paid less and less attention to Osorio, he worked hard at demonstrating to the King that he was the Prime Minister he needed because he was the only politician able to establish the monarchy by assembling a democracy just as he’d dismantled Francoism; he also worked at demonstrating that by contrast Fernández Miranda was just a spineless, old, unreal jurist, Fraga an indiscriminate bulldozer, Osorio a politician as pompous as he was inane and Areilza a well-dressed dead loss.

Читать дальше