Brenton was an unusually frank diplomat. His reward was a campaign of Kremlin-sponsored harassment: the pro-Putin youth group Nashi picketed his public events, jumped in front of his car, and waved unflattering placards outside the embassy. The placards bore a photo of the ambassador with the word ‘Loser’ stamped in red ink across his forehead.

* * *

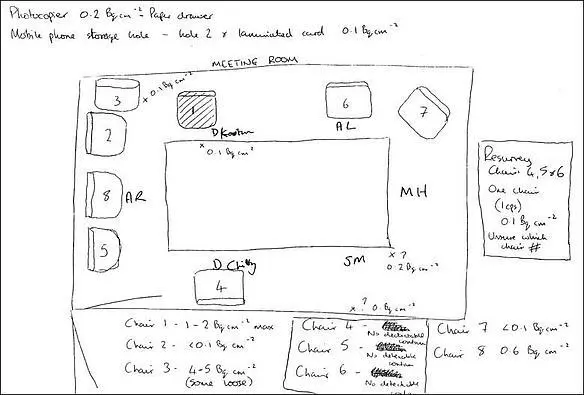

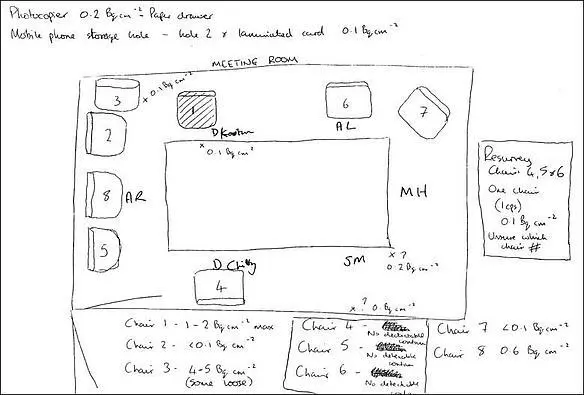

Days after my first break-in I had had my own meeting with MacLeod and an embassy security officer. I’d reported the intrusion to the Guardian and mentioned it to the embassy’s press attaché, who suggested I drop by. The venue for our chat was the embassy’s secure room from which mobile phones were banned. It looked rather like a music studio; a map of the Russian Federation hung on a wall. The room appeared to be the only part of the building which Putin’s security agents were unable to bug.

The conversation was helpful. And demystifying. It turned out the embassy knew all about FSB burglaries. They were Moscow’s worst-kept diplomatic secret, I learned. British and US diplomats and Russian nationals working for western missions found themselves on the receiving end of demonstrative break-ins. So, I later discovered, did Russian opposition activists. Recently, the break-ins had grown more frequent. ‘We don’t talk about it publicly. But no, you’re not going mad,’ the officer told me. ‘There’s no doubt this was the FSB. We have a thick file of similar cases. Generally we don’t make a fuss.’

The FSB’s tactics were weird, to say the least. They included defecating in loos, and not flushing afterwards; turning off fridges while the occupant was away on holiday; and introducing items of low value, like a cuddly toy, which hadn’t been there before. Sometimes a TV remote control would vanish, only to reappear weeks or months later. The same break-in team would install listening devices. Apparently, our flat was now bugged. ‘There’s not much you can do about them. Trying to identify or remove them will merely trigger the FSB’s return,’ the officer said.

On the surface, the FSB’s methods looked like bad-taste practical jokes. Actually, the KGB knew that such tactics – repeated over time – could have a destructive effect. The KGB developed and codified these techniques in the 1960s and 1970s. They had a name: operational psychology.

The Stasi, East Germany’s secret police, and the KGB’s sister organisation, employed the same tactics against dissidents, church leaders and others. One former Stasi officer told me proudly: ‘We always did it better than the Russians.’ Such methods were wonderfully deniable. It was easy to deride anyone who complained of sprite-like intrusions by unknown third parties as paranoid and mad.

I discovered that Stasi officers had written entire theses about what they called Zersetzung . The word in German means corrosion or decay. The goal of this harassment – in which the state’s hand remained hidden – was to ‘corrode’ a target so he or she ceased all hostile anti-state activity. With me, that appeared to be writing articles on themes the FSB deemed unacceptable. In the GDR, Zersetzung became a pseudo-scientific discipline. Putin had certainly come across Zersetzung when he served as a junior KGB spy in Dresden.

The embassy officer told me there was no evidence the agency hurt children, despite the ominous window left open next to my son’s bed. This was somewhat consoling.

* * *

That summer I received a letter from the FSB. It said that the agency had opened a criminal inquiry into Berezovsky’s Guardian interview. It added that Berezovsky had taken part in activities against state power, an offence under Russia’s penal code, article 278. An FSB agent called our Moscow office. He informed me I was being summoned as a ‘witness’ in connection with the case. I was to report to Lefortovo Prison. Oh, and I’d need a lawyer.

Three weeks later, I turned up outside Lefortovo jail. The letter had indicated the address – Energeticheskaya St 3a – useful since Lefortovo didn’t appear on maps. The building was as forbidding as I’d imagined, set among anonymous grey apartment blocks. There was a single tree in the courtyard. I entered through a heavy metal door with my lawyer, Gari Mirzoyan. Inside there was a large waiting room. It was devoid of tables and chairs. The agent on duty sat behind a silvered one-way window. He could see us; we couldn’t see him.

A hairy hand shot out and took my passport. Since there was nowhere to sit, we stood. After five minutes we were told to proceed to room 306, where Major Kuzmin was waiting for us. We walked down a corridor. The carpet was a worn red-green. I noticed an old-fashioned lift, with a heavy metal grille. It sank to the prison’s lower depths where Litvinenko had been kept. Above us were old-style security cameras. The atmosphere was one of shabby menace and institutional gloom. Seemingly little had changed since KGB times.

Major Kuzmin was younger than I expected: late twenties perhaps, with blond hair, neatly cut, and wearing a dark olive-green uniform. Lying on his desk was a colour photocopy of the Guardian ’s front-page Berezovsky scoop. I had explained that my role in the affair was a small one. Nonetheless, Kuzmin wanted to know under what circumstances the interview had taken place. Who was present? Was there a recording? Kuzmin typed my replies – there wasn’t much to say – two-fingered onto a computer.

It occurred to me that Kuzmin probably wasn’t the officer’s real name. Was he the guy who had been organising my apartment break-ins? There was nothing in the room that gave clues to his personality – no photos, one small spider plant. On the table in front of me was a bottle of fizzy water and a glass. Drinking didn’t seem like a good idea. The glass was engraved with four sets of initials in Cyrillic letters: Cheka, OGPU, KGB and FSB. These were the names of the Kremlin successive counter-revolutionary agencies, beginning with Dzerzhinsky’s Cheka .

After fifty-five minutes, the interview was over. Kuzmin gave me a witness statement to sign. We shook hands. He offered me a gift: a copy of the ‘Investigations department, Lefortovo Prison’ 2007 FSB calendar. It featured the FSB’s sword and shield logo, in dark red, against a purple background. Mirzoyan and I walked out into the corridor. It was empty. There was no noise or office chatter – merely a smooth and unnerving silence.

Despite the apparent end of the Cold War, the FSB clearly saw itself operating in the same tradition of Bolshevik conspiracy as its predecessors. The KGB’s and FSB’s goals were the same: to protect the state against all enemies. The agency’s neuralgic reaction to a single newspaper article suggested the Kremlin continued to view Berezovsky as its enemy in chief, a sort of modern Trotsky. Apparently I’d been marked down as Trotsky’s mini-helper and accomplice.

* * *

The FSB’s Lefortovo summons had the opposite reaction to what the agency may have intended. The Litvinenko case was inherently fascinating – and I was being told, through unsubtle KGB-style break-ins, not to investigate. The Kremlin’s extreme sensitivity to the topic suggested there was a lot to uncover. With digging and a little tenacity, perhaps it might be possible to find some answers.

In the summer of 2007, I met Dmitry Peskov, Putin’s urbane English-speaking press spokesman. It was a moment when the Kremlin still cared about Russia’s image abroad, one the Litvinenko affair had dented. A group of western correspondents had been summoned to one of Moscow’s fancier Italian restaurants. Peskov explained the affair from the Russian government’s perspective.

Читать дальше