Litvinenko continued to ring his friends. But he was fading. During one conversation with Suvorov his voice slowed up ‘like a gramophone’; his voice faltered; the mobile tumbled from his grasp. Suvorov promised to come and see him in ‘three or four days’ when he was better.

Later that day, Guy’s poisons unit came back with news. The biopsy pointed to a provisional diagnosis of poisoning by thallium, a deadly metal. But the levels of thallium were weirdly faint and not much above environmental levels – 30 nanomoles per litre. The data were confusing. Further verification was needed.

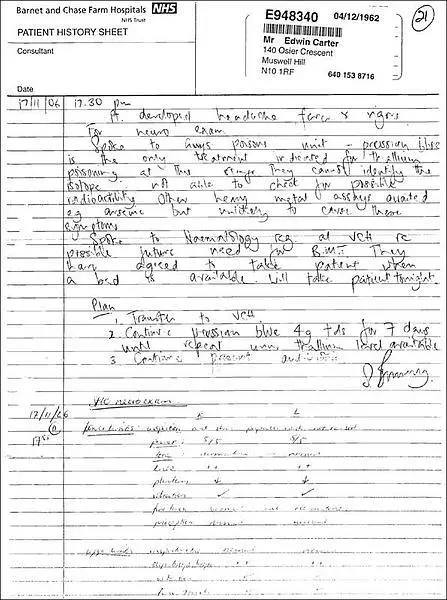

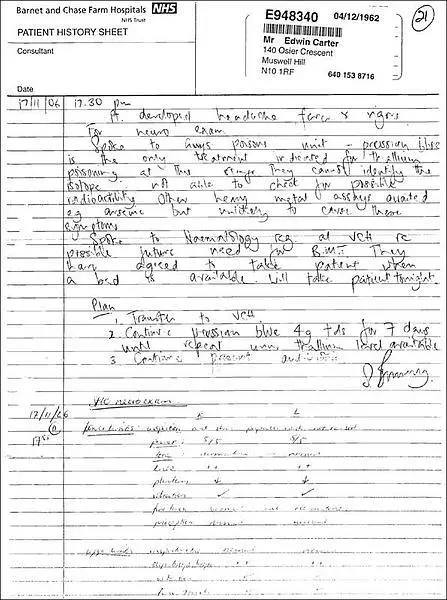

The diagnosis sounded an alarm. Medical staff contacted Scotland Yard and said they suspected a malicious poisoning. Virchis talked to Litvinenko. Litvinenko confirmed that the Russian intelligence service uses radioactive thallium. Doctors began treating him with Prussian blue, an antidote and counter-poison.

Plans were drawn up, meanwhile, to shift Litvinenko from Barnet to a specialist ward at University College Hospital in Bloomsbury, round the corner from the London university of the same name, and a short walk through a green square of veteran plane trees to the British Museum.

Litvinenko arrived at University College Hospital on 17 November. Just before midnight, two detectives appeared at his bedside.

* * *

To begin with, the British police had a confusing picture – a poisoned Russian who spoke poor English; a baffling plot involving visitors from Moscow; and a swirl of potential crime scenes. Two detectives, DI Brent Hyatt and Chris Hoar, from the Met’s specialist crime unit, interviewed Litvinenko in the critical-care unit on the sixteenth floor of University College Hospital. They address him rather quaintly as Edwin. He is a ‘significant witness’. There are eighteen interviews, lasting eight hours and fifty-seven minutes in total. These conversations stretch out over three days, from the early hours of 18 November until shortly before 9 p.m. on 20 November.

The interview transcripts were kept secret for eight and a half years, hidden in Scotland Yard’s case file, and stamped with the word ‘Restricted’, white capitals on a stark black rectangular background. Revealed in 2015, they are remarkable documents. They are, in effect, unique witness statements taken from a ghost. But Litvinenko is no ordinary ghost: he’s a ghost who uses his final reserves of energy to solve a chilling murder mystery – his own.

Litvinenko was a highly experienced detective. He knew how investigations worked. He was fastidious too: neatly collating case materials in a file, always employing a hole punch. In the interviews he sets out before the police in dispassionate terms the evidence of who might have poisoned him. He acknowledges: ‘I cannot blame these people directly because I have no proof.’

He’s an ideal witness – good with descriptions, heights, details. He draws up a list of suspects. There are three of them: the Italian Mario Scaramella; his business partner Andrei Lugovoi; and Lugovoi’s unpleasant Russian companion, whose name Litvinenko struggles to remember, and to whom he refers wrongly as ‘Volodia’ or ‘Vadim’.

DI Hyatt begins recording at eight minutes after midnight on 18 November. He introduces himself and his colleague Detective Sergeant Hoar, from the Met’s specialist crime directorate. Edwin gives his own name and address.

Hoar then says: ‘Thank you very much for that, Edwin. Edwin, we’re here investigating an allegation that somebody has poisoned you in an attempt to kill you.’ Hoar says that doctors have told him Edwin is suffering from ‘extremely high levels of thallium’ and ‘that is the cause of this illness’.

He continues: ‘Can I ask you to tell us what you think has happened to you and why?’

Medical staff had pre-briefed Hoar that Litvinenko spoke good English. In fact, Hoar discovered, this wasn’t the case. Litvinenko’s answers were sometimes spotty and confusing; after this first nocturnal session they took a police interpreter, Nina Tupper.

Despite these hurdles, Litvinenko is able to give a full account of his career in the FSB, his deepening conflict with the agency, and his unhappy encounter in 1998 with Putin. The case file records his words: ‘I have meeting with PUTIN, face to face. About forty minutes. I bring to PUTIN material about criminal inside FSB. PUTIN invite me to his team. I refuse. I know who is PUTIN. I have operation material against PUTIN in some … PUTIN have contract with one criminal group.’

Litvinenko talks of his ‘good relationship’ with the Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya, another Putin enemy, and her fear she was in danger. In spring 2006, they met in a branch of Caffè Nero in London. Litvinenko asked her what was wrong. She told him, ‘Alexander, I’m very afraid,’ and said that every time she said goodbye to her daughter and son she had the feeling she was looking at them ‘for the last time’. He urged her to leave Russia. She said she couldn’t, citing her ‘old parents’ and kids. In October 2006, the journalist was shot dead in the stairwell of her Moscow apartment. Previously, in 2004, Politkovskaya was herself poisoned after drinking tea served on a plane to the North Caucasus. She had been on her way to mediate with Chechen terrorists who seized a school in Beslan in North Ossetia. The poisoning was the work of the FSB, she wrote.

Politkovskaya’s murder in October left Litvinenko ‘very very shocked’, he says, adding: ‘I lost a lot of my friends’ and that human life in Russia is cheap. He tells detectives about a speech he made in the Frontline Club the previous month in which he accused Putin directly of having Politkovskaya killed.

From time to time, the interviews stop: the tape runs out; nurses come in to administer drugs; Litvinenko, suffering from diarrhoea, has to go to the bathroom. Mostly, though, he battles on. He tells Hyatt: ‘Meeting you is very important for my case.’ Litvinenko describes his encounter with Scaramella and gives a pocketbook description of the Italian: smart, grey suit, ‘crooked hair’, dark complexion, 1 m 72 cm – a typical man from Naples, with a light beard, and a ‘little bit fat’ round the middle.

The meeting, Litvinenko explains, was exasperating. Litvinenko says he was unimpressed by Scaramella’s fondness for cloak and dagger – they had agreed to meet at Piccadilly Circus next to the statue of Eros. Litvinenko got there first and found himself wondering about the ‘irony’ of the situation. ‘Why play the spies? To my mind, all these James Bonds verge on madness,’ he tells Hyatt.

In the Itsu restaurant, Scaramella delivers a list. It includes both their names. Supposedly, those who feature are targets for assassination by the Russian state. Litvinenko says he isn’t terrified by this development (which, in hindsight, appears to be a bizarre coincidence).

Rather, he’s offended by the grubbiness of the A4 sheet Scaramella handed him. ‘It was all dirty. I’ve worked a lot in my life with documents … When I am given papers like this I feel squeamish taking them into my hands,’ he says. He shows the two detectives his own working notebook. It’s immaculate, without any stains, even after two years. ‘Look how I make notes,’ he tells them.

But it is the two Russians who are at the centre of his suspicions. Litvinenko recounts his meeting with them at the Millennium Hotel. He says that he hadn’t been to the hotel before and had to find it on a map. He insists this ‘special’ information remain secret – not to be made public or shared with his wife Marina. ‘These people, it’s interesting. Most interesting,’ he muses. Litvinenko’s logic is that if Scaramella is the culprit he can easily be arrested in Italy. But if it’s the Russians they will be trickier to catch: ‘If this Andrei and Vadim from KGB poison me, if I speak it, KGB cover it [up].’

Читать дальше