Thus, on the Soviet side, the political level of interest in Spassky’s preparation was high, but not exceptionally so. One of the two secretaries of the Central Committee who ranked just below Brezhnev in authority, Mikhail Suslov was in ultimate charge of ideological matters and therefore chess. He apparently never officially discussed the match. The Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev does not appear to have involved himself in the match, though the figurehead president of the USSR, Nikolai Podgornii, sent a telegram of good wishes to Spassky. (It would have been unthinkable for Brezhnev himself to put his name to such a message.) When Spassky was plainly in trouble, Lev Abramov, the former head of the Chess Department of the State Sports Committee, wanted a team manager sent to Reykjavik. He went directly to one of Brezhnev’s aides, Konstantin Rusakov, to enlist his help. But Rusakov was abroad; there was no sense of urgency in the Kremlin, and Abramov’s initiative came to nothing.

As for the Americans, we know that Henry Kissinger made two calls to Fischer, but his almost day-by-day record of his time as national security adviser, The White House Years, contains no reference to them. There is no mention of the match in Nixon’s equally detailed Memoirs. The Soviet ambassador to Washington, D.C., Anatoli Dobrynin, told the authors that in his frequent contacts with Kissinger, the match never came up. Neither Fischer nor Spassky is cited in his book, In Confidence, even though Kissinger appears to have rung Fischer when he and the Soviet ambassador were the president’s guests in California, working and relaxing together while Fischer was threatening to fly home to Brooklyn.

In an interview for this book Dr. Kissinger reflected, “It was not the biggest decision I had to make in those days, but I thought it would help create an atmosphere of peaceful competition.” Indeed, what could be more competitive or more peaceful than a World Chess Championship? Yet the former national security adviser insists that, unlike most members of the public, he did not see the match as an aspect of the cold war or democracy versus communism.

By the end of 1971, the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), in its Strategic Survey of that year, compared 1971 to 1947 in that it marked a point where “the international system as a whole formed into a visibly new pattern.” One of America’s foremost strategic thinkers, Samuel P. Huntington, summed up geopolitics of the early 1970s: “All in all, the skies were filled with planes bearing diplomats to negotiations, and the air was rich with the promise of détente.” In its Strategic Survey for 1972, the IISS announced that the cold war was dead and buried.

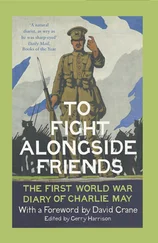

In the White House Map Room (left to right), the president’s national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, with the Soviet ambassador Anatoli Dobrynin. THE WHITE HOUSE

The broad period of the championship saw three successful summits, when Nixon visited Beijing and Moscow in 1972 and when Brezhnev visited Washington in June 1973. A torrent of talks, suggestions for talks, the promise of future agreements, and actual agreements cascaded into the diplomatic desert. These included the U.S.-Soviet Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT), the Interim Agreement on Certain Measures with Respect to Strategic Offensive Arms (SALT I), and the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty. Eventually, 150 agreements were signed and 11 joint commissions established. A handshake in space in 1975 could be seen as the culminating moment.

The essential difference between détente and the previous era, Dr. Kissinger argues, is that Nixon believed that negotiations were still possible and desirable with the Soviet regime as it was. Previous U.S. administrations held that any meaningful dialogue with the Soviets would have to await a fundamental transformation in the Soviet political system. Nixon turned this thinking on its head. He maintained that if international stability could be created over a long enough period, the monolithic Soviet system would be unable to resist change.

What was Brezhnev’s view of détente? Essentially that it was a mechanism for dealing with problems between governments and that this foreign policy was distinct from and not applicable to domestic affairs. Or, if there was a connection, it was a matter of preserving the Soviet system, not liberalizing it. Indeed, in the Soviet Union, repression stiffened in the détente years.

For the Kremlin, importantly, détente also meant America’s acknowledgment that the USSR was a military superpower and a political equal. As the Soviet foreign minister Andrei Gromyko said in 1971: “There is no question of any significance that can be decided without the Soviet Union or in opposition to it.” To Brezhnev, recognition of equality was of greater consequence than SALT. The Soviet leader could reassure himself and the Soviet people that the so-called correlation of forces in the world was tilting toward communism; the Soviet Union was riding the wave of history that would wash capitalism away. An article in Komsomolskaia Pravda justifying the policy was entitled “A Triumph of Realism.” Détente did not mark the end of global political competition. On the contrary, now was the time to step up the struggle; at this juncture in history, the circumstances were exceptionally favorable to the onward march of socialism. (Kissinger saw Brezhnev’s sensitivity on political equality as showing his psychological insecurity: “What a more secure leader might have regarded as a cliché or condescension, he treated as a welcome sign of our seriousness.”)

Détente also offered immediate practical and material payoffs for the adversarial superpowers. The Soviets wanted trade to avoid root-and-branch economic reform. The United States hoped détente would give the Soviets a stake in stability and temper their adventurousness abroad.

Thus, there was necessarily a contradiction at the heart of détente—between cooperation and competition. Rivalry between the two superpowers remained intense—as seen in the long list of Nixon’s reactive measures against perceived Soviet threats. The administration took action to counter the construction of a Soviet naval base in Cuba (U.S. spy planes had photographed a football field being set out when the Cuban national game was baseball), the movement of Soviet surface-to-air missiles to the Suez Canal, the Soviet role in the Indo-Pakistan war, and Brezhnev’s aggressiveness and apparent readiness for military intervention in the Arab-Israeli war.

Both sides worked on improving their weaponry and extending their influence. And both sides had problems with allies and client states whose interests did not align with theirs, or who felt their interests were subordinated to those of the superpower. For example, during the first days of Fischer-Spassky, the Egyptian president, Anwar al-Sadat, expelled the 20,000 Soviet advisers and technicians based in his country, together with Soviet combat and reconnaissance aircraft. Angered by Moscow’s refusal to give him advanced weapons, Sadat initiated secret contacts with the Americans.

When the match was over, some of the press picked up these opposing themes—suspicious antagonism against peaceful competition. On the one hand, Fischer and Spassky represented their countries, and the match, according to the broadsheets, embodied East-West confrontation, particularly given the Soviet claim that its chess supremacy was the outcome of its superior ideology. On the other hand, no nationalist rivalry had been sparked off. Many Americans had supported Spassky, and many Russians had quietly rooted for Fischer. All in all, concluded The New York Times, the match had a unique political importance in terms of improved U.S.-USSR relations.

Читать дальше