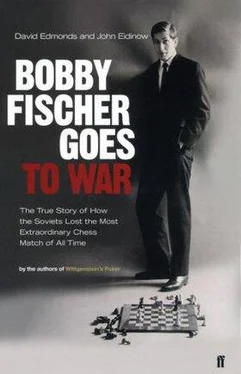

Davis then intervenes. He attempts to persuade the committee that the written protest was a mere formality; they must get to the essence. Schmid should not have started the clock because Fischer had already protested against the presence of television cameras in the hall. They had not been withdrawn. Thus, the conditions were not in order, in accordance with his demands. Ergo, Fischer was not late.

At this point, Geller interjects a counterargument. The rules said that players must be at the game on time. Now that the match was under way, it was too late to protest against the general conditions—there could be complaints only about specific games, and they must be made at the game itself.

As it is his judgment that is under question, Schmid withdraws. That same day at a news conference, Arnlaugsson announces the committee’s ruling. The protest is accepted as delivered in time, but Schmid’s decision to start the clock is affirmed. The cameras would be discussed later with the participants. Fischer’s loss is approved.

Everything to do with Fischer now goes into reverse: in place of the question “Will he comer?” is “Will he leave?” Lombardy, Cramer, Marshall in New York, all scurry around, organizing telegrams from fans in the States beseeching him to stay put. But in the event, an equal number of people, unprompted, send telegrams of condemnation.

While all this is going on, Henry Kissinger is on duty in California, helping to entertain the Soviet ambassador Anatoli Dobrynin at Nixon’s western White House, Casa Pacifica, on the beach at San Clemente. It is a considerable honor for Dobrynin as well as an opportunity for long, informal conversations with Kissinger on U.S.-Soviet relations. They sunbathe on the beach, and Kissinger takes the ambassador and his wife to Hollywood to mingle with the stars. There is no record of them meeting the Marx Brothers, though Hitchcock proposes a suspense film set in the Kremlin. “The time is not yet ripe,” intones Dobrynin. At some stage, Kissinger is said to have found time to put in a call to Reykjavik 22322, the hotel Loftleidir.

Fox’s chief cameraman, Gissli Gestsson, tells the story of how he, Gestsson, was in Fischer’s suite when the telephone rang: “That is the strangest call I ever witnessed in my life. I could hear Henry Kissinger giving him this pep talk like a coach, saying, ‘You’re our man up against the Commies.’ It was unbelievable.” Quite. Bearing in mind that the whole problem was caused by Fischer’s wrath directed at the cameramen, being admitted to Fischer’s side and hearing him take a call from the U.S. president’s right-hand man must have been the scoop of the match.

Fischer’s mind is unchanged, and again the match has descended into Marx Brothers burlesque. There are scenes involving flight reservations, plots to detain Fischer in Reykjavik to prevent his escape, and aborted drives to the airport. Marshall recalls:

We mainly communicated by telex. But one guy with a telephone would occasionally get through to us. We kept receiving messages about Fischer being booked on various planes; a plane to New York, a plane to Greenland, every flight that went out of Reykjavik had Fischer on the flight list. And we were getting these wonderfully droll messages from an Icelander about how Fischer had booked himself on these flights and that Cramer had gone to the airport to try to dissuade him. And there were all these exciting car chases going on.

Fischer off-stage continues to command almost all the attention. In the press, much of it makes for uncomfortable reading. The Washington Post agonizes that “Fischer has alienated millions of chess enthusiasts around the world.” All the expectations of him have “turned to ashes, with Bobby Fischer himself as arsonist.” The correspondent of Agence France-Presse writes that Fischer has crossed the boundaries of all proper behavior.

In contrast, the front pages of the Icelandic press are adorned with pictures of the well-mannered and apparently carefree world champion walking, fishing for salmon, or playing tennis. No doubt these help reassure the organizers that they can focus their efforts on keeping Fischer in the match and let the world champion await the challenger’s decision. It is difficult to resist the conjecture that their attitude is also influenced by the cold war. The West-East, us-them relationship is instrumental in what follows. The Americans and the Icelanders, partners in NATO, both with free market economies and democratically elected governments, are “us,” the Soviet chess delegation is “them.” Not being a true “them” is to prove Spassky’s undoing.

13. BLOOD IN THE BACK ROOM

Spassky was a gentleman. Gentlemen may win the ladies, but gentlemen lose at chess.

— VIKTOR KORCHNOI

Whatever the impression given in the press, the champion was in deep dismay. He had no wish to retain the title by default. To calm him down after the forfeit was announced, Viktor Ivonin took him on a long walk. Nothing was turning out as the champion had anticipated. He had wanted the focus of the combat to be on the aesthetic creations at the chessboard. “I was very patient with Fischer, but he is impossible to understand. And the organizers are making concessions to him. Remember how they said, ‘Bobby Fischer is ill and in hospital.…’”

Whatever the impression given in the press, the champion was in deep dismay. He had no wish to retain the title by default. To calm him down after the forfeit was announced, Viktor Ivonin took him on a long walk. Nothing was turning out as the champion had anticipated. He had wanted the focus of the combat to be on the aesthetic creations at the chessboard. “I was very patient with Fischer, but he is impossible to understand. And the organizers are making concessions to him. Remember how they said, ‘Bobby Fischer is ill and in hospital.…’”

Ivonin had watched Spassky’s expression as he waited for Fischer for that one hour. By the end, the deputy minister was fervently hoping Fischer would not arrive, his champion looked so empty and overwhelmed. All the uncertainties of the preceding days had returned in greater measure. Spassky had gained a point but with a pyrrhic victory. Ivonin noted that in conversation, Spassky talked obsessively about Fischer. The deputy minister found that disturbing. The sensitive Spassky was unable to switch his thoughts to more relaxing matters.

At four in the afternoon, after the forfeit was confirmed, Icelandic officials, Schmid and Moeller, the head of the match committee, representatives of the two sides, Fox, the cameramen, some journalists, and diplomats all met in the hall to reexamine the conditions and check Fox’s cameras. No one had any queries.

Iceland’s chief auditory expert, Curt Baldursson, conducted an official test of the noise made by the cameras. These were brand-new American models and were what was called self-blimped—constructed to be soundless during filming. Baldursson received no pay for his labors but was given, instead, free entrance to the rest of the match. For his experiment, he brought along a state-of-the-art sound-level meter. “The meter didn’t register anything close to levels that could have been picked up by a human ear, so either Fischer had extrasensory faculties or this was part of a poker game.” The noise level was measured at fifty-five decibels with the cameras running and fifty-five decibels with them turned off. Baldursson wrote out a report that Fischer peremptorily dismissed. The cameras were moved behind the walls of the set, looking through tiny windows. In Ivonin’s judgment, they were unnoticeable.

The American millionaire chess fan Isaac Turover joined the group. He played a game on the official board with Ivonin. The Soviet politician took the opportunity of probing and trying out Fischer’s chair, taking pains not to be noticed.

Someone wondered aloud whether it would be the last game there. Turover said that if Fischer was not given the point back, the match was over. An Icelandic journalist asked Ivonin for his opinion. He replied that the Soviet side had not breached the rules and was not going to breach them. Nor were they going to allow anyone else to.

Читать дальше

Whatever the impression given in the press, the champion was in deep dismay. He had no wish to retain the title by default. To calm him down after the forfeit was announced, Viktor Ivonin took him on a long walk. Nothing was turning out as the champion had anticipated. He had wanted the focus of the combat to be on the aesthetic creations at the chessboard. “I was very patient with Fischer, but he is impossible to understand. And the organizers are making concessions to him. Remember how they said, ‘Bobby Fischer is ill and in hospital.…’”

Whatever the impression given in the press, the champion was in deep dismay. He had no wish to retain the title by default. To calm him down after the forfeit was announced, Viktor Ivonin took him on a long walk. Nothing was turning out as the champion had anticipated. He had wanted the focus of the combat to be on the aesthetic creations at the chessboard. “I was very patient with Fischer, but he is impossible to understand. And the organizers are making concessions to him. Remember how they said, ‘Bobby Fischer is ill and in hospital.…’”