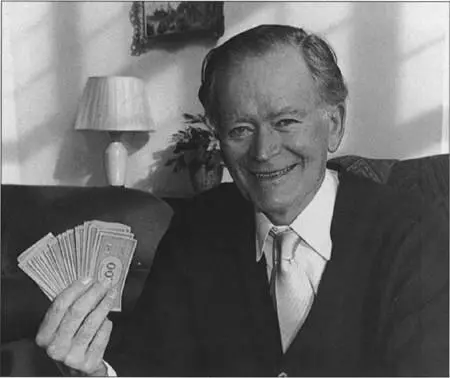

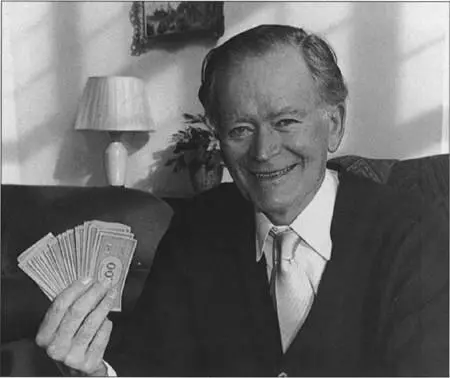

Millionaire businessman James Slater. He put up the money to save the match. JAMES SLATER

Slater’s offer made headlines in London’s Evening Standard. His house was soon swarming with reporters. When he returned from work, he enlightened his astonished wife: “I had a good idea on the way to the office.” The good idea was couched in challenging terms: “If he isn’t afraid of Spassky, then I have removed the element of money.”

It is not altogether clear how the British offer finally persuaded Fischer. Paul Marshall certainly had a hand, initially pushing it as the answer to all Fischer’s financial demands. “But he wouldn’t accept it. His experiences with people promising things had taught him not to believe them, particularly with money. And he wanted proof. And he said no.” Marshall tried to change his mind. Phoning Barden, the attorney took his place in the gallery of callers that saved the match. “I said if I were them, I would rephrase the offer. Slater should say he didn’t think his money was at risk, because Fischer was just making excuses. He should say that deep down Fischer was frightened. I said Bobby might be piqued by that challenge—and he was. I knew Bobby was very, very competitive and combative and would not like to be thought of as a chicken.” Slater denies this version of events. He maintains it was always his idea to express his offer as a taunt. He never spoke to Fischer and never received a word of gratitude from him. “Fischer is known to be rude, graceless, possibly insane. I didn’t do it to be thanked. I did it because it would be good for chess.” In the meantime, there were reports that Mrs. Marshall, a professional photographer, informed the press where Fischer was staying, in an attempt to smoke him out of his bunker.

Kissinger’s intervention, the extra money, the wording of the offer, the media camped outside the house in Cedar Lane, perhaps also information from Reykjavik that disqualification would follow if Fischer failed to arrive by midday on 4 July—one or a combination of these tipped the balance.

On 3 July, Fischer drove through the pre—Independence Day evening traffic to JFK Airport. At Kennedy, he transferred to an Icelandic Airlines station wagon and was smuggled on board a plane, flight 202A. The flight, scheduled for 7:30 P.M., took off at 10:04 P.M. All the other passengers had been kept waiting, and a few had been bumped off the flight. In Moscow, the Foreign Ministry rang Viktor Ivonin to report that the American challenger was on his way.

Marshall told the press that the problem had never been the money. It was the principle. His client felt Iceland was not treating this match or his countrymen with the dignity that it, and they, deserved. His private view was that before Slater’s offer, Fischer “had already in effect defaulted. He was pretty well determined not to go.”

Marshall chaperoned Fischer on the journey to Iceland, accompanied by his wife, Bette. Fischer had initially prohibited Marshall from bringing her along, claiming she would distract her husband. Marshall circumvented this injunction by booking a seat for her at the other end of the plane. “And a quarter of the way through the flight, I figured Bobby was above jumping, so I asked my wife to come back and he welcomed her very pleasantly, as though the previous conversation hadn’t happened.”

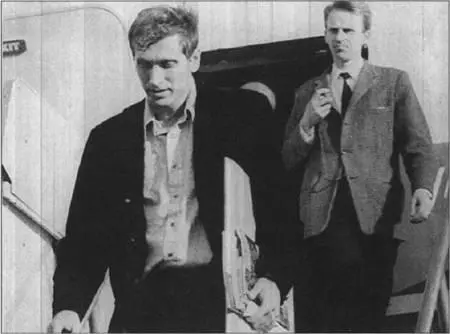

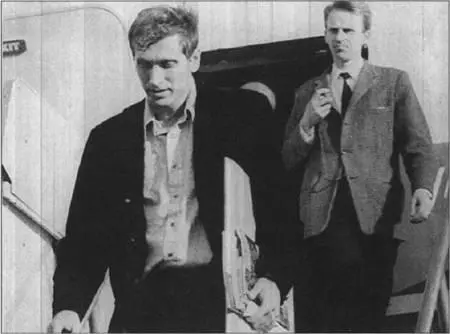

The Icelandic grandmaster Fridrik Olafsson had the role of Fischer’s official greeter, meeting him at his seat, escorting him to the receiving line, performing introductions, and driving with him to Reykjavik. As a precaution, all journalists and photographers had initially been corraled into the airport building—but a public relations officer at Icelandic Airlines was tempted by the fruit of worldwide publicity and fell. He cut the reporters loose.

Olafsson’s plan crumbled as Fischer arrived at the top of the gangway in the early hours of 4 July.

All went well until Bobby came out on the ramp and saw the crowd of journalists and photographers waiting for him below. Seeing this, Bobby dashed down, hardly noticing the dignitaries that had lined up there for him, pushed aside the journalists and photographers, who were in his way, and jumped into the nearest car of the convoy. While this was going on, Ihad been left standing in the doorway, staring in amazement at the commotion and looking at Bobby dashing down the steps.

Olafsson was a phlegmatic, dignified man who reserved all his aggression for the chessboard. (One of the world’s leading grandmasters, he had little real competition at home. He was, says Thorarinsson, “a genius who came out of nowhere.”)

Gradually things calmed down; the members of Bobby’s party got out of the plane and went to their cars. Soon the convoy was on its way to Reykjavik with a police escort at a speed of 150 kilometers an hour—the protocol for a visit by a head of state.

There was a sting in the tail for the organizers of the match, says Olafsson. “This was Fischer’s first impression of Iceland—and it was that the organizers didn’t keep their word.”

Thorarinsson was now a man relieved, even if Fischer had ignored him in the chaos of the reception at Keflavik airport. He sought out Spassky, to thank him for his advice to refer upward to a more senior rank. But when they met, Spassky, for once, was angry. He charged Thorarinsson with having broken a promise. Suddenly the truth dawned on the Icelander. “I realized that I had misunderstood the whole thing. The Soviet government felt that Spassky was being humiliated and they had called him back. Spassky had wanted me to involve the higher authorities in Moscow, not Washington.” Now that Fischer was in Reykjavik, Thorarinsson had a new battle on his hands: to keep Spassky there, too.

Olafsson (right) standing. ASSOCIATED PRESS

This atmosphere of unreality is likely to prevail throughout the match….

— THEODORE TREMBLAY, CABLE

From the airport, Fischer was taken straight to the house, placed at his disposal in a quiet road in a half-built suburb called Wodaland. The jackpot prize in a forthcoming state lottery, it had not been lived in. (The winner would later complain that it was not strictly new, as promised in the lottery promotion.) When Fischer showed up, there were still bricks and mounds of earth on the street. From here, it was a two-mile hike to the center of town. Fischer soon abandoned it in favor of the other accommodation reserved for him—a three-room suite at the hotel Loftleidir. While this was one of Iceland’s best hotels, it was functional rather than luxurious, looking like an airport terminal, low-rise, set off from a big thoroughfare, with a façade of precast rectangular windows and paneling.

From the airport, Fischer was taken straight to the house, placed at his disposal in a quiet road in a half-built suburb called Wodaland. The jackpot prize in a forthcoming state lottery, it had not been lived in. (The winner would later complain that it was not strictly new, as promised in the lottery promotion.) When Fischer showed up, there were still bricks and mounds of earth on the street. From here, it was a two-mile hike to the center of town. Fischer soon abandoned it in favor of the other accommodation reserved for him—a three-room suite at the hotel Loftleidir. While this was one of Iceland’s best hotels, it was functional rather than luxurious, looking like an airport terminal, low-rise, set off from a big thoroughfare, with a façade of precast rectangular windows and paneling.

Fischer granted the BBC an interview, conducted by a well-known science correspondent, James Burke, and produced by Bob Toner, who has good reason to remember the occasion: “We started recording and Fischer looked very bored and for two reels we got nothing, twenty minutes of nothing, just one-line answers. I thought my career was disappearing down the tubes. But then, in between reels, he asked Burke what kind of events he normally covered. Burke said he had reported on the Apollo launches, and you could see Fischer’s interest light up. And he said, ‘You mean you go to Houston, you go to launch pads?’ ‘Yes,’ said Burke, ‘I know Neil Armstrong very well.’ After that Fischer couldn’t stop talking.”

Читать дальше

From the airport, Fischer was taken straight to the house, placed at his disposal in a quiet road in a half-built suburb called Wodaland. The jackpot prize in a forthcoming state lottery, it had not been lived in. (The winner would later complain that it was not strictly new, as promised in the lottery promotion.) When Fischer showed up, there were still bricks and mounds of earth on the street. From here, it was a two-mile hike to the center of town. Fischer soon abandoned it in favor of the other accommodation reserved for him—a three-room suite at the hotel Loftleidir. While this was one of Iceland’s best hotels, it was functional rather than luxurious, looking like an airport terminal, low-rise, set off from a big thoroughfare, with a façade of precast rectangular windows and paneling.

From the airport, Fischer was taken straight to the house, placed at his disposal in a quiet road in a half-built suburb called Wodaland. The jackpot prize in a forthcoming state lottery, it had not been lived in. (The winner would later complain that it was not strictly new, as promised in the lottery promotion.) When Fischer showed up, there were still bricks and mounds of earth on the street. From here, it was a two-mile hike to the center of town. Fischer soon abandoned it in favor of the other accommodation reserved for him—a three-room suite at the hotel Loftleidir. While this was one of Iceland’s best hotels, it was functional rather than luxurious, looking like an airport terminal, low-rise, set off from a big thoroughfare, with a façade of precast rectangular windows and paneling.