Chapter 12

AFRICA: A PLACE TO LEAVE ALONE

The U.S. strategy of maintaining the balance of power between nation-states in every region of the world assumes two things: first, that there are nation-states in the region, and second, that some have enough power to assert themselves. Absent these factors, there is no fabric of regional power to manage. There is also no system for internal stability or coherence. Such is the fate of Africa, a region that can be divided in many ways but as yet is united in none.

Geographically, Africa falls easily into four regions. First, there is North Africa, forming the southern shore of the Mediterranean basin. Second, there is the western shore of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, known as the Horn of Africa. Then there is the region between the Atlantic and the southern Sahara known as West Africa, and finally a large southern region, extending along a line from Gabon to Congo to Kenya to the Cape of Good Hope.

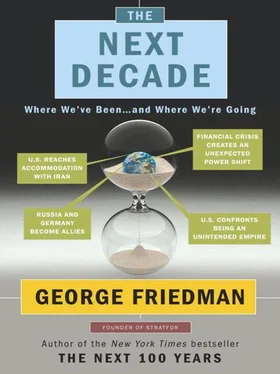

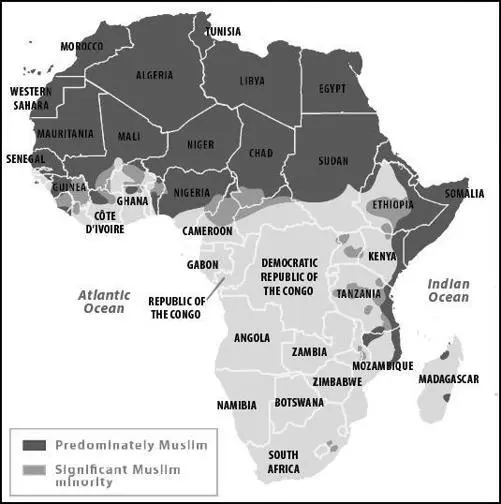

Using the criterion of religion, Africa can be divided into just two parts: Muslim and non-Muslim. Islam dominates North Africa, the northern regions of West Africa, and the west coast of the Indian Ocean basin as far as Tanzania. Islam does not dominate the northern coast of the Atlantic in West Africa, nor has it made major inroads into the southern cone beyond the Indian Ocean coast.

Islam in Africa

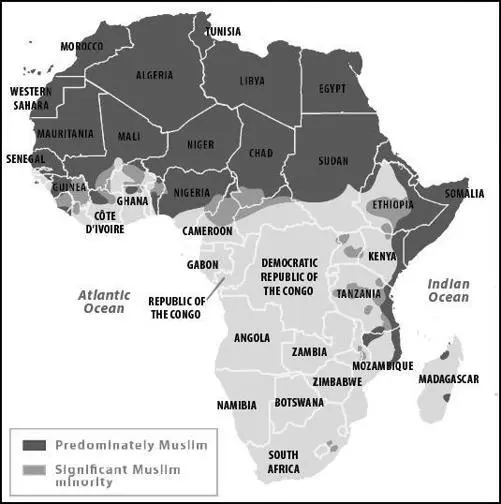

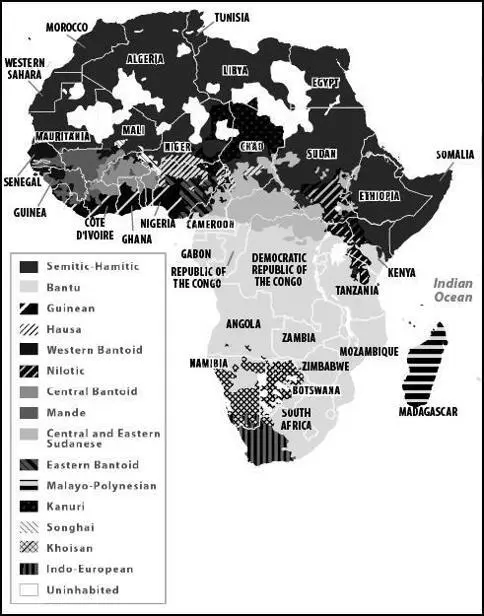

The linguistic map probably gives us the best sense of Africa’s broad regions. But language as a way of looking at Africa is infinitely more complex, because hundreds of languages are widely used and many more are spoken by small groups. Given this linguistic diversity, it is ironic that the common tongue within nations is frequently the language of the imperialists: Arabic, English, French, Spanish, or Portuguese. Even in North Africa, where Arabic lies over everything, there are areas where the European languages of past empires remain an anachronistic residue.

Ethnolinguistic Groups in Africa

A similar irony surrounds what is probably the least meaningful way of trying to make sense of Africa, which is in terms of contemporary borders. Many of these are also holdovers representing the divisions among European empires that have retreated, leaving behind their administrative boundaries. The real African dynamic begins to emerge when we consider that these boundaries not only define states that try to preside over multiple and hostile nations contained within, but often divide nations between two contemporary countries. Thus, while there may be African states, there are—North Africa aside—few nation-states.

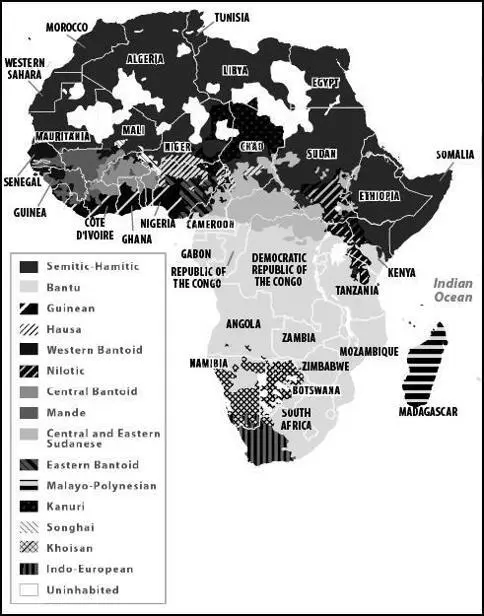

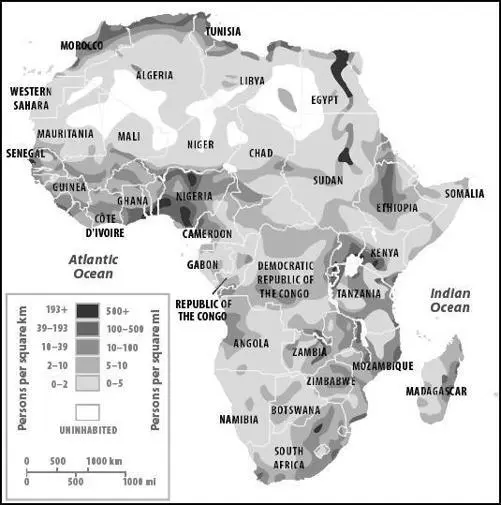

Population Density in Africa

Finally, we can look at Africa in terms of where people live. Africa’s three major population centers are the Nile River basin, Nigeria, and the Great Lakes region of central Africa, including Rwanda, Uganda, and Kenya. These may give a sense that Africa is overpopulated, and it is true that given the level of poverty, there may well be too many people trying to extract a living from Africa’s meager economy. But much of the continent is in fact sparsely populated compared to the rest of the world. Africa’s topography of deserts and rain forests makes this inevitable.

Even when we look at these centers of population, we find that the political boundaries and the national boundaries have little to do with each other. Rather than being a foundation for power, then, population density merely increases instability and weakness. Instability occurs when divided populations occupy the same spaces.

Nigeria, for instance, ought to be the major regional power, since it is also a major oil exporter and therefore has the revenues to build power. But for Nigeria the very existence of oil has generated constant internal conflict; the wealth does not go to a central infrastructure of state and businesses but is diverted and dissipated by parochial rivalries. Rather than serving as the foundation of national unity, oil wealth has merely financed chaos based on the cultural, religious, and ethnic differences among Nigeria’s people. This makes Nigeria a state without a nation. To be more precise, it is a state presiding over multiple hostile nations, some of which are divided by state borders. In the same way, the population groupings within Rwanda, Uganda, and Kenya are divided, rather than united, by the national identities assigned to them. At times wars have created uneasy states, as in Angola, but long-term stability is hard to find throughout.

Only in Egypt do the nation and the state coincide, which is why from time to time Egypt becomes a major power. But the dynamic of North Africa, which is predominantly a part of the Mediterranean basin, is very different from that of the rest of the continent. Thus when I use the term Africa from now on, I exclude North Africa, which has been dealt with in an earlier chapter.

Another irony is that while Africans have an intense sense of community—which the West often denigrates as merely tribal or clan-based—their sense of a shared fate has never extended to larger aggregations of fellow citizens. This is because the state has not grown organically out of the nation. Instead, the arrangements instituted by Arab and European imperialism have left the continent in chaos.

The only way out of chaos is power, and effective power must be located in a state that derives from and controls a coherent nation. This does not mean that there can’t be multinational states, such as Russia, or even states representing only part of a nation, such as the two Koreas. But it does mean that the state has to preside over people with a genuine sense of shared identity and mutual interest.

There are three possible outcomes worth considering for Africa. The first is the current path of global charity, but the system of international aid that now dominates so much of African public life cannot possibly have any lasting impact, because it does not address the fundamental problem of the irrationality of African borders. At best it can ameliorate some local problems. At worst it can become a system that enhances corruption among both recipients and donors. The latter is more frequently the case, and truth be known, few donors really believe that the aid they provide solves the problems.

The second path is the reappearance of a foreign imperialism that will create some foundation for stable life, but this is not likely. The reason that both the Arab and the European imperial phases ended as readily as they did was that even though there were profits to be made in Africa, the cost was high. Africa’s economic output is primarily in raw materials, and there are simpler ways to obtain these commodities than by sending in military forces and colonial administrators. Corporations making deals with existing governments or warlords can get the job done much more cheaply without taking on the responsibility of governing. Today’s corporate imperialism allows foreign powers to go in, take what they want at the lowest possible cost, and leave when they are done.

The third and most likely path is several generations of warfare, out of which will grow a continent where nations are forged into states with legitimacy. As harsh as it may sound, nations are born in conflict, and it is through the experience of war that people gain a sense of shared fate. This is true not only in the founding of a nation but over the course of a nation’s history. The United States, Germany, or Saudi Arabia are all nations that were forged in the battles that gave rise to them. War is not sufficient, but the tragedy of the human condition is that the thing that makes us most human—community—originates in the inhumanity of war.

Читать дальше