Sheri Fink

WAR HOSPITAL

A True Story of Surgery and Survival

To my parents and grandparents

and the doctors and nurses of eastern Bosnia

Medical ethics in time of armed conflict is identical to medical ethics in time of peace… The primary obligation of the physician is his professional duty; in performing his professional duty, the physician’s supreme guide is his conscience.

The primary task of the medical professional is to preserve health and save life.

—

Regulations in Time of Armed Conflict , World Medical Association, 1956, 1957, 1983

The doctor’s fundamental role is to alleviate the distress of his or her fellow men, and no motive, whether personal, collective or political shall prevail against this higher purpose.

—

The Declaration of Tokyo , World Medical Association, 1975

MAIN CHARACTERS WITH AGES AT THE BEGINNING OF THE BOSNIAN WAR IN SPRING 1992

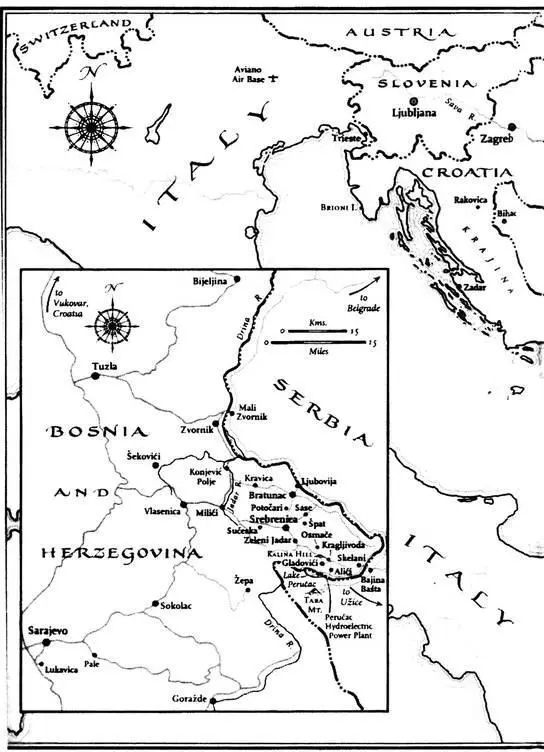

ALÍĆ, EJUB, 32 (AH-leetch, Ey-yoob)—Physician at Srebrenica (SREBREHN-EET-SA) war hospital, separated from his wife and young son. Born in a small village and worked as an internal medicine resident in Bosnia before the war. Heavyset, with a round face, a good sense of humor, and a weakness for plum brandy.

DACHY, ERIC, 30 (Dah-shee)—Head of the Doctors Without Borders mission in Belgrade, Serbia. Responsible for aid to eastern Bosnia. Belgian family practitioner. Passionate and outspoken. Wears a trademark black leather jacket and ponytail.

DAUTBAŠIĆ, FATIMA, 26 (dah-UTE-bah-sheetch, fah-TEE-mah)—Physician at Srebrenica war hospital. Family practitioner before the war. Girlfriend of Dr. Ilijaz Pilav. Has long, dark hair, beautiful eyes, and a high-pitched laugh.

LAZIĆ, BORO, 27 (LAH-zeetch, BOE-roe)—Physician with Bosnian Serb forces across the front lines from Srebrenica. Friends with several Srebrenica doctors and nurses before the war. Slender, with light brown hair, blue-green eyes, and a boyish face.

MUNJKANOVIĆ, NEDRET, 31 (mooy-KAHN-oh-veetch, NED-reht)—Surgical resident who volunteered to walk to Srebrenica across enemy territory in August 1993. Handsome, with an athletic build, a clean-shaven face, and a highly charismatic, if temperamental, personality.

PILAV, ILIJAZ, 28 (PEE-lahv, ILL-ee-ahz)—Physician at Srebrenica war hospital. Born in a small village near Dr. Ejub Alić. Worked as a general physician before the war. Boyfriend of Dr. Fatima Dautbašić. A tall, gaunt, and unassuming man with a scraggly beard and mustache.

THE OTHERS

BOSNIAN DOCTORS WORKING IN SREBRENICA:

DŽANIĆ, NIJAZ (JAHN-eetch, NEE-yahz)—Physician at wartime clinic for civilians in Srebrenica. Internist in Srebrenica before the war.

HASANOVIĆ, AVDO (hah-SAHN-oh-veetch, AV-doe)—Director of Srebrenica war hospital. Pediatrician before the war.

STANIĆ, BRANKA (STAHN-eetch, BRAHN-kah)—Physician at Srebrenica war hospital. Graduated from medical school just before start of war and went to work in Switzerland. A Catholic Croat in a mostly Muslim town.

DOCTORS WITHOUT BORDERS DOCTORS, NURSES, AND LOGISTICIANS:

PONTUS, THIERRY (PON-toose, TEAR-y)—Belgian surgeon. Worked in Srebrenica in 1993.

WILLEMS, PIET (VI-lems, pete)—Belgian surgeon. Worked in Srebrenica in 1993.

ULENS, HANS (OO-lens, hans)—Dutch logistician. Worked in Srebrenica from 1993 to 1994.

DUONG, NEAK (dwong, neek)—French surgeon. Worked in Srebrenica in 1994.

SCHMITZ, CHRISTINA—German nurse. Worked in Srebrenica in 1995.

THE SURGEON SHOWED UP wearing gym clothes. We met in the smokefilled interior of one of Bosnia’s best hotel cafés, where, gesturing, drawing, and occasionally lifting his tall, athletic frame from his seat to underline a point, he told me the story that had made him famous. It began with his hike across twenty-five miles of enemy territory to reach the besieged eastern Bosnian town of Srebrenica. There, along with a small band of village doctors, most barely out of medical school and not one a surgeon, he ministered to the medical needs of 50,000 people. Rudimentary equipment and the lack of electricity, running water, and often anesthetics were just the beginning of the hardships. These doctors and nurses were visited by nearly every imaginable affliction of modern war.

The handsome, dark-haired doctor regaled me for two full days, interrupting our conversation only to greet well-wishers, who called him by his first name, “Dr. Nedret.” His casual dress reflected confidence and charisma befitting a man who embarks on a journey knowing that it can lead to one of only two endpoints: martyrdom or magnificence. Nedret told me a story of triumph and tragedy, heroism and human weakness, of friendship and love surviving against all odds in a climate of anger and vengeance. All this took place in the town of Srebrenica, which, attacked in the presence of U.N. soldiers, became a central testing ground for U.S.-European relations, NATO’s post–Cold War significance, and what U.S. President George Bush senior dubbed “the new world order.”

* * *

WHAT LED ME TO Dr. Nedret Mujkanović (and later his less hyperbolic but equally impressive fellow doctors of Srebrenica) was a conference on “Medicine, War, and Peace” that I attended my final year as a medical student. The winter conference took place in an unheated Bosnian medical school auditorium beneath blown-out windows, unrepaired two years after the war. One by one, doctors, nurses, and aid workers related wartime experiences that had pitted their personal struggle for survival against their duty to practice medicine.

Those stories led me to reflect on my previous conception of war medicine. The popular culture depicts war as a rite of passage, a proving ground for the famous surgeon-pioneers, and a culture medium for history’s greatest medical advances. The words of a British physician from the turn of the last century epitomize this view: “How large and various is the experience of the battlefield and how fertile the blood of warriors in the rearing of good surgeons.” This cheery quotation graces the preface to NATO’s official war surgery handbook and is so well-known that it was repeated to me by a war doctor in Bosnia (who attributed it, interestingly, to a Russian).

But even the peacetime practice of medicine in the most technically advanced country of the world sometimes crushes doctors’ personal lives and professional development. Years of rigorous, all-consuming training, unreasonable hours, sleep deprivation, pressure to be superhuman and perfectionistic, and repeated exposure to life-and-death dilemmas often dehumanize doctors and lead them to burn out and neglect their own health and well-being. Having known American doctors who committed suicide, abused drugs, or made serious mistakes under the pressures of normal medical practice, I wondered whether a “fertile rearing” was really what the Bosnian war doctors had experienced. I returned to Bosnia the following year to find out.

Those first two days I spent with the war surgeon, Dr. Nedret, offered nothing to contradict and much to support my initial, romantic notions. War had left him an optimist. It gave him plenty of chances to hone technical skills, devise ingenious adaptations to seemingly impossible situations, and perform uplifting, sustaining, purposeful work in bleak and tragic circumstances. As I probed deeper and met more doctors who’d worked in Srebrenica, though, I learned that the constant grind of not only living through war, but also treating its most severely affected victims, led some lifesavers to hopelessness, despair, and even criminal activity.

Читать дальше