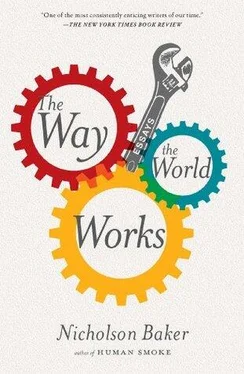

Nicholson Baker - The Way the World Works

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nicholson Baker - The Way the World Works» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Simon & Schuster, Жанр: Публицистика, Критика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Way the World Works

- Автор:

- Издательство:Simon & Schuster

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Way the World Works: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Way the World Works»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

), here assembles his best short pieces from the last fifteen years.

The Way the World Works

OED

Modern Warfare 2

Through all these pieces, many written for

, and

, Baker shines the light of an inexpugnable curiosity.

is a keen-minded, generous-spirited compendium by a modern American master.

The Way the World Works — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Way the World Works», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Bad things happen to books all the time, and then the books hold the record in their pages of those disasters, too. Books become water-soaked and writhe into the shapes of giant clams, and they wait in warehouses for dealers to cut pages out of them for piecemeal sale. Over many decades, paper changes color and becomes more fragile (though considerably less fragile than some paper-apocalyptists have claimed) — the particular fragility of an old volume is part of what it has to tell us.

Some of the most evocative photographs in this collection are the ones in which a book is allowed to fall open slightly, so that we glimpse some of the foreshortened secrets (an upward-glancing face, a colosseum) it may hold. Pages, for the most part, live out their long lives in the dark, keeping hidden what inky burdens they bear, pressed tightly against their neighbors, communicating nothing, until suddenly, like the lightbulb in the refrigerator that seems to be always on but almost never is, one of them is called upon to speak — and it does.

(2002)

No Step

In 1994, I took a nap on an airplane. On waking, I pushed up the oval window shade and looked outside. The window was surprisingly hot to the touch: incoming sunlight had bounced off the closed shade, heating it up. And the wing looked hot, too, like something you would use to press a shirt. But it wasn’t hot; volumes of freezing wind were flowing over and under it — invisibly wispy, top-of-Mount-Everest wind. Suddenly I felt an injustice in being so close to the wing, closer than any other passenger, and yet being unable to determine for myself, by touch, what temperature it was. Would my finger stick to it?

The plane turned, so that the long sickle-shape of sun-dazzle slid from the wing and fell to earth; and then, in the shadow of the fuselage, dozens of Phillips-head screws appeared, like stars coming out in an evening sky. Some of these wing screws surrounded a stenciled message, which I read. The message was: WARNING WET FUEL CELL DO NOT REMOVE.

A few months later, on a Boeing 757, I was given a window seat with an excellent view of the right engine. The engine was painted a dark glossy blue; it hung below the wing, shiny and huge, bobbling a little in the turbulence, like a large breast or a horse’s testicle. There was a message on the engine. HOIST POINT, it said.

In April 1996 I looked out directly over another wing. Its leading edge was made of shiny naked metal, but the middle of the wing had been painted a pinky beige color. The painted part looked like a path — and because the wing tapered, the edges of the path angled in and converged at the far end, so that it seemed by a trick of perspective to extend for miles, disappearing finally at the blue horizon. If I climbed out the window and set off down that path, I’d have to walk carefully at first, with my knees bent to steady myself against the rush of the invisible, very cold wind, which would otherwise flip me off into the void. But I would get my wind legs soon enough. When I was a quarter of a mile down the wing, I’d turn and wave at the passengers. Then, shrugging my rucksack higher on my shoulders, I would set off again.

There were no words for me on that wing. But on the return flight I got a seat farther forward in the cabin, near the left engine. This engine said: CAUTION RELEASE UPPER FWD LATCH ON R.H. AND L.H. COWL BEFORE OPERATING. And it said: WARNING STAND CLEAR OF HAZARD AREAS WHILE ENGINE IS RUNNING. The hazard areas were diagrammed on a little picture — it was not difficult to heed this warning, since the areas were all out in empty space. I spent a long time looking at the engine. It was an impassive object, a dead weight. You know when propellers are turning, because you can see them turn, but this piece of machinery gave no sign that it was what was pushing us forward through the sky.

Usually I don’t become interested in the wing until the plane has taken off. Before that there are plenty of other things to look at — the joking baggage handlers pulling back the curtain on the first car of a three-car suitcase train; the half-height service trucks lowering their conveyors; the beleaguered patches of dry grass making a go of it between two runways; the drooped windsock. As you turn onto the runway, you sometimes get a glimpse of it stretching ahead, and sometimes you can even see the plane that was in line ahead of you dipping up, lifting its neck as it begins to grab the air. Before the forward pull that begins a takeoff, the cabin lights and air pressure come on, as if the pilot has awakened to the full measure of his responsibility; and then, looking down, you see the black tire marks on the asphalt sliding past, traces of heavier-than-usual landings. (It still seems faintly worrisome that the same runway can be used for takeoffs and landings.) Some of the black rubber-marks are on a slight bias to the straightaway, and there are more and more of them, a sudden crowding of what looks like Japanese calligraphy, and then fewer again as you heave past the place where most incoming planes land. You’re gaining speed now. Fat yellow lines swoop in and join the center yellow line of your runway, like the curves at the end of LP records. And finally you’re up: you may see a clump of service buildings, or a lake, or many tiny blue swimming pools, or a long, straight bridge, and then you go higher until there is nothing but distant earth padded here and there with cloud. Then, out of a pleasant sort of loneliness, ignoring the person who is sitting next to you, you begin to want to get to know the wing and its engine.

In April 1998, sitting in an emergency exit row on the way to Denver, I was surprised by how sharp-edged some mountains were. I was used to the blunt mountains of three-dimensional plastic topographical maps, which are pleasing to the fingertips. But real mountains would scrape your palm if you tried to feel them that way. I passed a salt lake, perhaps the Great Salt Lake, which had a white deposit on its edges like a chemistry experiment. And then I gave up on the world and looked out at my new friend, the wing. It had nothing to say to me at first, no words that I could see; but then, when I put my head as close as I could to the window and looked down, I could make out two arrows. These were painted on a textured non-slip area near where the wing joined the fuselage. We passengers were not meant to see these arrows from our seats: they were there in case of a catastrophe, when we would hurry out the window and leap off the wing onto an inflatable rubber slide. How fast do you go down a slide? Fast enough to break a leg, I would think. I wouldn’t want to leap onto that slide, but I like the arrows.

On the return from Denver, the wing, attached to an Airbus A-230, said DO NOT WALK OUTSIDE THIS AREA. I had no interest in walking outside that area. The clouds were enormous flat-bottomed patties resting heavily on an ocean of low-pressure air. A few days after that, on a Boeing 767—one of the ones with the mis-designed call buttons on the sides of the armrest which people press when they are trying to adjust the volume on their headphones, so that when the movie begins, the cabin is filled with unintended dinging calls for flight attendants — I had, just after takeoff, a quick, pleasing view of the neighborhood where I lived, visible just above the lump of the left engine, whose crest bore the words NO STEP. And then in June of that year I again saw NO STEP on the top of a jet engine, while the plane I was on was still on the ground. A man was leaning into the engine, so that only his legs were visible. On the wing there were faint wind-wear lines streaking like aurora borealises from behind one of a group of eight little flathead screws. Two weeks later, the engine of a Boeing 757 said: HOIST POINT SLEEVE ONLY, and THRUST REVERSE ACTUATOR ACCESS, and LEAVE 3 INCH MAXIMUM GAP BETWEEN FAIRINGS PRIOR TO SLIDING AFT AND LATCHING, and SAFETY LINE ATTACH POINT.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Way the World Works»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Way the World Works» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Way the World Works» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.