In the large Tambacounda station, the locomotive broke down. Some valves burst, and a stream of oil trickled down the embankment. The local boys hastily filled their bottles and cans with it. Nothing is wasted here. If grain spills, it will be carefully gathered; if a pitcher of water cracks, every drop possible will be saved and drunk.

It looked as if we were going to be standing here quite some time. A crowd of curious onlookers from the town quickly assembled. I encouraged the two Scots to step outside, have a look around, talk a little. They categorically refused. They did not want to meet or speak to anyone. They did not want to get to know anyone, visit with anyone. If someone started to approach them, they turned and walked away. Ideally they would prefer simply to run. Their attitude was the result of limited but bad experience. They had seen that whenever they engaged in conversation with anyone, that that person always wanted something from them later. Different things: help securing a scholarship, employment, money. He or she invariably had sick parents, younger siblings in their care, and had not eaten for several days now. These complaints and lamentations were constantly repeated. They didn’t know how to react. They felt helpless. Finally, discouraged and disappointed, they made a joint decision: no contact, encounters, conversations. And they were now sticking by this.

I told the Scots that these requests on the part of the people they had met follow from the belief of many Africans that the white man has everything, or that, in any event, he has a great deal, much more than the black man. And if a white man suddenly crosses an African’s path, it’s as if a chicken has laid him a golden egg. He must take advantage of this opportunity — he must remain focused, must not miss his chance. All the more so because so many of these people really have nothing, need everything, and want so much.

But this behavior is also a manifestation of a great cultural difference, a dissimilarity of expectations. African culture generally is a culture of exchange. You give me something, and it is my responsibility to reciprocate. It is not only my responsibility; my dignity, my honor, my humanity require it. Human relations assume their highest form during the process of exchange. The union of two young people, who through their progeny prolong man’s presence on earth and ensure the continuation of the species — why, even that union comes into being through an act of interclan exchange: the woman is traded for various material goods indispensible to her clan. In this culture, everything assumes the form of a gift, a present demanding requital. The unreciprocated gift lies heavily on the head of the one who has received it, torments his conscience, and can even bring down misfortune, illness, death. Thus the receipt of a present is a signal, a goad to immediate reciprocal action, to a quick restoring of equilibrium: I received? I repay!

Many misunderstandings arise because one side does not understand that things of a very different order can be exchanged; for example, we can exchange something of symbolic value for something of material value, and vice versa. If an African approaches the Scots, he showers various gifts on them: he bestows upon them his presence and attention, imparts information (warning them about thieves, for example), ensures their safety, etc. It goes without saying that this generous man now awaits reciprocity, recompense, the satisfaction of his expectations. It is to his astonishment that he observes the Scots make sour faces; more, that they turn on their heels and walk away!

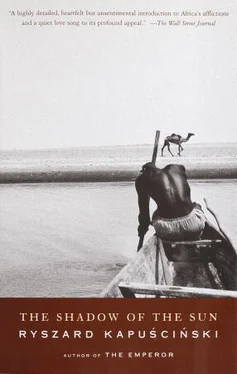

In the evening we continued on our way. It grew a bit cooler, one could breathe. We were traveling east, deeper and deeper into the Sahel, into Africa’s interior. The train tracks led through Goudiry, Diboli, and a larger town already across the border in Mali: Kayes. At each station Madame Diuf shopped. The compartment was already bursting with oranges, watermelons, papayas, grapes; now she bought carved stools, brass candleholders, Chinese towels, French soaps. Each transaction was punctuated with her triumphant cries: “Voilà, m’sieurs, dames! Combien cela coute à Bamako? Cinq fois plus cher! Et à Dakar? Dix fois! Bon Dieu! Quel achat!” She now took up the entire length of one banquette. I lost my seat entirely, but even the Scots had only a small sliver left on the other side of the compartment, now packed to the rafters with fruit, laundry detergents, blouses, bunches of dried herbs, sacks of seeds, millet, and rice.

I had the impression — I was a little drowsy and felt that I was coming down with a fever — that Madame was becoming ever more immense, that there was more and more of her. Her full bou-bou caught the wind coming in through the window, swelled, ballooned like a sail, undulated and fluttered. She was returning home to Bamako, proud of her cheap purchases. Satisfied, victorious, she filled the whole compartment with her person.

Looking at Madame Diuf, at her ubiquitousness, her dynamic and commanding presence, her monopolizing and unapologetic omnipotence, I realized how much Africa had changed. I remembered how I had ridden this railroad years ago. I was then alone in my compartment; no one dared to disturb the peace and encroach upon the comfort of a European. And now the proprietress of a stall in Bamako, the mistress of this land, without so much as blinking an eye, pushes three Europeans out of the compartment, demonstrating unequivocally that there is no room for them here.

We reached Bamako at four in the morning. The station was full of people, a dense crowd stood on the platform. A band of feverish boys burst into our compartment: Madame’s crew, come to carry her purchases. I walked out of the compartment. Suddenly, I heard a man shouting. Pushing my way in that direction, I came upon a Frenchman in a torn shirt sitting on the platform, moaning and cursing. He had been robbed of everything the second he stepped off the train. All he had left was the handle of his suitcase, and now, brandishing this scrap of leather, he was shaking his fist at the world.

In Bamako I live in a guest house called the Centre d’Acceuil, run by Spanish nuns. The rooms are cheap — a bed, mosquito netting. The bad thing about the Centre d’Acceuil is that although there are ten rooms for rent, there is only one shower. Moreover, it is constantly occupied these days by a young Norwegian, who came here not realizing just how hot it gets in Bamako. The African interior is always white-hot. It is a plateau relentlessly bombarded by the rays of the sun, which appears to be suspended directly above the earth here: make one careless gesture, it seems, try leaving the shade, and you will go up in flames. For newcomers from Europe, there is also a psychological factor at work: they know they are in the depths of hell, far from the sea, from lands with a gentler climate, and this feeling of distance, of exile, of imprisonment, makes life here even harder for them to bear. The Norwegian, after several suffocating, sweltering days, decided to leave everything and return home. But he had to wait for the plane. And the only way he could survive until then, he concluded, was by never coming out from under the shower.

There is no question: the temperatures here during the dry season are overwhelming. The street where I live is dead still from early morning. People slump motionlessly against walls, in passageways, beneath entrance gates. They sprawl in the shade of eucalyptus and mimosa trees, beneath a great, spreading mango and a tall, flaming amaranthine bougainvillea. They sit on a long bench in front of the bar run by a Mauritanian, and on empty crates in front of the corner grocery shop. Despite having observed them all at length on several occasions, I have been unable to determine what exactly it is that they are doing. Perhaps that’s because they are not doing anything. They don’t even talk. They resemble people sitting for hours in a doctor’s waiting room. Although this is perhaps not the best comparison, because in the end the doctor will arrive. Here no one arrives. No one arrives, no one leaves. The air trembles, undulates, stirs restlessly, like over a kettle of boiling water.

Читать дальше