Ryszard Kapuscinski

The Soccer War

RYSZARD KAPUŚCIŃSKI

The Soccer War

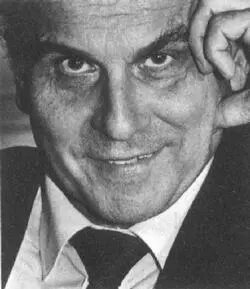

Ryszard Kapuściński was born in 1932. During four decades reporting on Asia, Latin America, and Africa, he befriended Che Guevara, Salvador Allende, and Patrice Lumumba. He witnessed twenty-seven coups and revolutions and was sentenced to death four times. His books have been translated into nineteen languages. He died in 2007.

I am living on a raft in a side-street in the merchant district of Accra. The raft stands on pilings, two-storeys high, and is called the Hotel Metropol. In the rainy season this architectural monstrosity rots and festers with mould, and in the dry months it expands at the joints and cracks. But it does not fall apart! In the middle of the raft there is a construction that has been partitioned into eight compartments. These are our rooms. The remaining space, surrounded by a balustrade, is called the veranda. There we have a big table for meals and a few small folding tables where we drink whiskey and beer.

In the tropics, drinking is obligatory. In Europe, the first thing two people say when they meet is ‘Hello. What’s new?’ When people greet each other in the tropics, they say ‘What would you like to drink?’ They frequently drink during the daytime, but in the evening the drinking is mandatory; the drinking is premeditated. After all, it is the evening that shades into night, and it is the night that lies in wait for anyone reckless enough to have spurned alcohol.

The tropical night is a hardened ally of all the world’s makers of whiskey, cognac, liqueurs, schnapps and beers, and the person who denies them their sales is assailed by the night’s ultimate weapon: sleeplessness. Insomnia is always wearing, but in the tropics it is killing. A person punished all day by the sun, by a thirst that can’t be satisfied, maltreated and weakened, has to sleep.

He has to. And then he cannot!

It is too stuffy. Damp, sticky air fills the room. But then, it’s not air. It’s wet cotton. Inhale, and it’s like swallowing a ball of cotton dipped in warm water. It’s unbearable. It nauseates, it prostrates, it unhinges. The mosquitoes sting, the monkeys scream. Your body is sticky with sweat, repulsive to touch. Time stands still. Sleep will not come. At six in the morning, the same invariable six in the morning all year round, the sun rises. Its rays increase the dead steam-bath closeness. You should get up. But you don’t have the strength. You don’t tie your shoes because the effort of bending over is too much. You feel worn out like an old pair of slippers. You feel used up, toothless, baggy. You are tormented by undefined longings, nostalgias, dusky pessimisms. You wait for the day to pass, for the night to pass, for all of it, damn it to hell, finally to pass.

So you drink. Against the night, against the depression, against the foulness floating in the bucket of your fate. That’s the only struggle you’re capable of.

Uncle Wally drinks because it does his lungs some good. He has tuberculosis. He is thin, and each breath comes hard, with a wheeze. He takes a seat on the veranda and calls, ‘Papa! One!’ Papa goes to the bar and brings him a bottle. Uncle Wally’s hand starts trembling. He pours some whiskey into the glass and tops it up with cold water. He downs the drink and starts on another. Tears come to his eyes, and he shakes with a voiceless sob. Ruin, waste. He is from London, was a carpenter in England. The war brought him to Africa. He stayed. He is still a carpenter, but he has taken to drink and carries round that battered lung that he never treats. With what could he get treatment? Half his money goes to the hotel, and the other half for whiskey. He has nothing, literally nothing. His shirt is in tatters; his only pair of trousers full of patches; his sandals crumbling. His impeccably elegant countrymen have cursed him and driven him away. They have forbidden him to say that he is English. Dirty lump. Fifty-four years old. What is left for him? Drink a little whiskey and start pushing up daisies.

So he drinks and waits for his shot at the daisies. ‘Don’t get angry at the racists,’ he tells me. ‘Don’t get all wound up about the bourgeoisie. Do you think they’ll plant you in different dirt when your number comes up?’

His love for Ann. My God: love. Ann came around here when she needed money for a taxi fare. Once she had been Papa’s girl, demanding her petty compensation — two shillings. Her face was tattooed. She came from the northern tribe of the Nankani, and in the north they canker the faces of their infants. The custom dates from when the southern tribes conquered the northern ones and sold them to the whites as slaves, and so the northerners disfigured their foreheads, cheeks and noses to make themselves unsaleable goods. In the Nankani language the words for ugly and free mean the same thing. Synonyms.

Ann had soft, sensual eyes. All of her was in those eyes. She would look at somebody long and kittenishly, and when she saw her gaze working she would laugh and say, ‘Give me two shillings for cab-fare.’

Uncle Wally always came over. He would pour her a whiskey, grow lachrymose and smile. He told her, ‘Ann, stay with me and I’ll stop drinking. I’ll buy you a car.’

She answered, ‘What do I need a car for? I prefer to make love.’

He said, ‘We’ll make love.’

She asked, ‘Where?’ Uncle Wally got up from his table; it was only a few steps to his room. He opened the door, grasping the handle, trembling. The dark coop contained an iron bed and a small chest.

Ann burst out laughing. ‘Here? Here? My love has to live in palaces. In the palaces of the white kings!’

We were watching. Papa went over, tapped Ann on the shoulder and mumbled, ‘Shove off.’ She left gaily, waving to us—‘Bye bye.’ Uncle Wally returned to his table. He picked up the bottle as though to drink it straight down in one go, but before he had finished it, he was slumping in his chair. We carried the old desperado into his chicken coop of a room, to the iron bed, and laid him on the white sheet — without Ann.

After that, he told me, ‘Red, the only woman who won’t betray you is your mother. Don’t count on anyone else.’ I loved listening to him. He was wise. He told me: ‘The African praying mantis is more honest than our wives. Do you know the mantis? Courtships don’t last long in the world of the mantis. The insects have their wedding ceremony, leave for the honeymoon, and in the morning the female bites the male to death. Why bother tormenting him for a lifetime? The result is the same, isn’t it? And whatever is done more quickly is done more honestly.’

The bitter tone in Uncle Wally’s outpourings always disquiets Papa. Papa keeps us on a short leash. Before I go out I have to tell him where I am going and why. Otherwise there will be a scene. ‘I worry about you,’ Papa screams. When an Arab screams there’s no reason to take it seriously. It’s just his way of speaking. And Papa is an Arab, a Lebanese. Habib Zacca. He has been leasing the hotel for a year. ‘Since the Big Crash,’ Papa says. Oh, yes, he got wiped out.

‘Zacca?’ a friend of his cries, ‘Zacca — he was a millionaire. A millionaire! Zacca had a villa, cars, shops, orchards.’

‘When my watch stopped, I’d throw it out of the window,’ Papa sighs. ‘The doors of my house were always open. A crowd of guests every day. Come on in, eat, drink, whatever you want. And now? They don’t even say hello. I have to go and present myself to the gluttons who ate and drank me out of thousands.’ Papa came to Ghana twenty years ago. He began with a fabric shop and made a great fortune, which he lost afterwards, in a year. He lost it at the races. ‘The horses ate me, Red.’

Читать дальше