For me they have an additional interest. To read the detective novels of these four women is to learn more about the England in which they lived and worked than most popular social histories can provide, and in particular about the status of women in the years between the wars. For this reason, if no other, they should have a chapter to themselves.

Agatha’s best work is, like P. G. Wodehouse and Noel Coward’s best work, the most characteristic pleasure-writing of this epoch and will appear one day in all decent literary histories. As writing it is not distinguished, but as story it is superb.

Robert Graves, letter, 15 July 1944

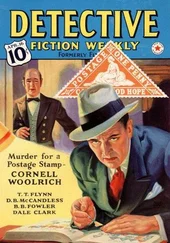

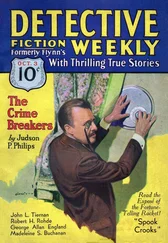

REAMS OF paper have been expended on attempts to explore the secret of Agatha Christie’s success. Writers who explore the phenomenon not uncommonly begin with the arithmetic of her achievements: outsold only by the Bible and Shakespeare, translated into over one hundred foreign languages, author of the longest-running play ever seen on the London stage and, in addition, recipient of awards that success usually affords only to the highest literary talent-a Dame of the British Empire and an honorary degree of Doctor of Literature from Oxford University. The perennial question remains, how did this gently reared, essentially Edwardian lady do it?

“Check with our legal people if we can publish a detective story in which the murderer turns out to be the author.”

Certainly Christie’s universal appeal doesn’t lie in blood or violence. Not for her the bullet-ridden corpses down Raymond Chandler’s mean city streets, the urban jungle of the wisecracking, fast-shooting, sardonic private eye or the careful psychological examination of human depravity. Although both her best-known detectives, Poirot and Miss Marple, occasionally investigated murder overseas, her natural world as perceived by her readers is a romanticised cosy English village rooted in nostalgia, with its ordered hierarchy: the wealthy squire (often with a new young wife of mysterious antecedence), the retired irascible colonel, the village doctor and the district nurse, the chemist (useful for the purchase of poison), the gossiping spinsters behind their lace curtains, the parson in his vicarage, all moving predictably in their social hierarchy like pieces on a chessboard. Her style is neither original nor elegant but it is workmanlike. It does what is required of it. She employs no great psychological subtlety in her characterisation; her villains and suspects are drawn in broad and clear outlines and, perhaps because of this, they have a universality which readers worldwide can instantly recognise and feel at home with. Above all she is a literary conjuror who places her pasteboard characters face downwards and shuffles them with practised cunning. Game after game we are confident that this time we will turn up the card with the face of the true murderer, and time after time she defeats us. And with a Christie mystery no suspect can safely be eliminated, even the narrator of the story. With other mystery writers of the Golden Age we can be reasonably confident that the murderer won’t be one of the attractive young lovers, a policeman, a servant or a child, but Agatha Christie has no favourites with either murderer or victim. Most mystery writers jib, as do I, at killing the very young, but Agatha Christie is tough, as ready to murder a child, admittedly a precocious unappealing one, as she is to despatch a blackmailer. With Mrs. Christie, as with real life, the only certainty is death.

Perhaps her greatest strength was that she never overstepped the limits of her talent. She knew precisely what she could do and she did it well. For over fifty years this shy and conventional woman produced murder mysteries of extraordinarily imaginative duplicity. With her immense output the quality is inevitably uneven-some of the later books in particular show a sad falling-off-but at her best the ingenuity is dazzling. Her prime skill as a storyteller is the talent to deceive, and it is possible to identify some of the tricks, often verbal, by which she gently seduces us into self-deception. In time we almost match the cunning of the author. We beware of entering that most lethal of rooms, the country house library, we become suspicious of the engaging ne’er-do-well returning from foreign parts and take careful note of mirrors, twins and androgynous names. She is particularly fond of a version of the eternal triangle in which a couple, apparently happily engaged or married, are menaced by a third person, sometimes predatory and rich. When the victim is murdered there is little mystery about the chief suspect. Only at the end of the book does Miss Christie turn the triangle round and we recognise that it was that way up all the time. And her clues are brilliantly designed to confuse. The butler goes over to peer closely at a calendar. She has planted in our mind the suspicion that a crucial clue relates to dates and times, but the clue is, in fact, that the butler is shortsighted.

Both the trickery and the final solution are invariably more ingenious than believable. The books are mild intellectual puzzles, not credible blueprints for real murder. In Death on the Nile , for example, the murderer is required to dash round the deck of a crowded river-steamer, acting with split-second precision and depending on not being observed either by passengers or by crew. In another book we are told that the murderer unscrews the digits of a number on the door of a hostel room, so luring the victim to the wrong room. In real life we never go unerringly to the room we want; we identify it by the floor and by the numbers on adjoining doors. In Dumb Witness the clue is that a brooch made of initials is glimpsed in a mirror at night. But the brooch is worn by a woman in a dressing-gown-the last garment on which a heavy brooch would normally be pinned. But to the Christie aficionado this is mere quibbling. And indeed it does seem ungracious to point out inconsistencies or incredulities in books which are primarily intended to entertain-a far from ignoble aim-and in which the reader is in general treated fairly and falls more often than not into a pit of his own devising.

The moral basis of the books is unambiguous and simple, epitomised by Poirot’s declaration: “I have a bourgeois attitude to murder: I disapprove of it.” But even the horror of murder is sanitised; the necessary violence is perfunctorily described, there is no grief, no loss, an absence of outrage. We feel that at the end of the book the victim will get up, wipe off the artificial blood and be restored to life. The last thing we get from a Christie novel is the disturbing presence of evil. Admittedly Poirot and Miss Marple occasionally used the word, but with no more relevance than if they were referring to the smell of bad drains. One of the secrets of her universal and enduring appeal is that it excludes all disturbing emotions; those are for the real world from which we are escaping, not for St. Mary Mead. All the problems and uncertainties of life are subsumed in the one central problem: the identity of the killer. And we know that, by the end of the book, this will be satisfactorily solved and peace and order restored to that mythical village whose inhabitants, apparently so harmless and familiar, prove so enigmatic, so surprising in their ingenious villainy.

Agatha Christie hasn’t in my view had a profound influence on the later development of the detective story. She wasn’t an innovative writer and had no interest in exploring the possibilities of the genre. What she consistently provided is a strong and exciting narrative, the challenge of a puzzle, an accommodating and accessible style and original detectives in Poirot and Miss Marple, whom readers can encounter in book after book with the comfortable assurance that they are meeting old friends. Her main influence on contemporary crime writers was to affirm the popularity and importance of ingenuity in clue plotting and of surprise in the final solution, thus helping significantly to set the limited range and the conventions of what were to become the books of the Golden Age. Dorothy L. Sayers could have been thinking of Agatha Christie when she wrote:

Читать дальше