Although women detectives play little part in the novels of the Golden Age, somewhat surprisingly they appeared very early in the history of crime writing. To discuss their exploits and examine their significance to the genre requires a whole book-which has, indeed, been written by Patricia Craig and Mary Cadogan in their fascinating The Lady Investigates (1981). I am particularly sorry not to have encountered Lady Molly of Scotland Yard, the creation of Baroness Orczy, more famous for the Scarlet Pimpernel stories. The majority of Baroness Orczy’s detective stories were written before the full flowering of the Golden Age, but in 1925 she published Unravelled Knots , which foreshadowed later English armchair detectives who, physically disabled and unable to sally forth, solved crimes by a mixture of intuition and clues brought to them by a peripatetic colleague, of which Josephine Tey’s The Daughter of Time is probably the best-known English example. Lady Molly appeared in 1910 and one can only agree with the “high-born Frenchwoman” who describes her as “a true-hearted English woman, the finest product on God’s earth, after all’s said and done.” Baroness Orczy was probably aware that none of her readers in 1910 would think that consorting with the police in a criminal investigation was a proper job for a lady, even for a true-hearted English woman, but Lady Molly, like others of her time, is sacrificing herself to vindicate her husband, who is languishing in Dartmoor prison, wrongly convicted of murder. Needless to say, Scotland Yard officers are at Lady Molly’s feet and adulation is inspired in everyone she encounters. The story is told by her sidekick, Mary Granard, who used to be her maid and who idolises her dear lady’s beauty, charm, brains and style, and the marvellous intuition which, in Mary’s opinion, made her the most wonderful psychologist of her time. The relationship between them is one of sickening sentimentality. Mary, who obviously serves the function of a Watson, complained while on a case that there was something she didn’t understand. “‘No, and you won’t until we get there,’ Lady Molly replied, running up to me and kissing me in her pretty engaging way.” I suspect that Lady Molly’s husband was in no hurry to be liberated from Dartmoor prison.

Not surprisingly, given the talents of many of the writers, the Golden Age detective stories were competently and sometimes very well written, and some of the best will endure. Nevertheless, subtlety of characterisation, a setting which came alive for the reader and credibility of motive were often subjugated, particularly in the humdrums, to the demand to provide an intriguing and mysterious plot. Writers vied with each other in their search for an original method of murder and for clues of increasing ingenuity and complexity. Webster has written that death has ten thousand doors to let out life, and it seems that most of them have at one time or another been used. Unfortunate victims were despatched by licking poisoned stamps, being battered to death by church bells, stunned by a falling pot, stabbed with an icicle, poisoned by cat claws and not infrequently found dead in locked and barred rooms with looks of appalling terror on their faces. This world was summed up by William Trevor, the Anglo-Irish novelist and short story writer, when he spoke of reading detective stories as a child in his acceptance speech on winning a literary award in 1999.

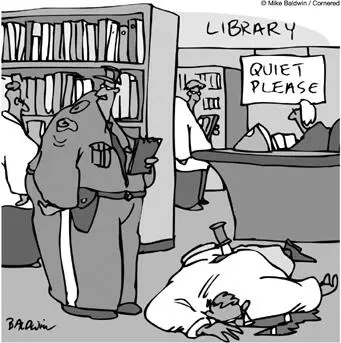

All over England, it seemed to me, bodies were being discovered by housemaids in libraries. Village poison pens were tirelessly at work. There was murder in Mayfair, on trains, in airships, in Palm Court lounges, between the acts. Golfers stumbled over corpses on fairways. Chief Constables awoke to them in their gardens.

We had nothing like it in West Cork.

Nor in West Kensington either.

These novels are, of course, paradoxical. They deal with violent death and violent emotions, but they are novels of escape. We are required to feel no real pity for the victim, no empathy for the murderer, no sympathy for the falsely accused. For whomever the bell tolls, it doesn’t toll for us. Whatever our secret terrors, we are not the body on the library floor. And in the end, by the grace of Poirot’s little grey cells, all will be well-except of course with the murderer, but he deserves all that’s coming to him. All the mysteries will be explained, all the problems solved, and peace and order will return to that mythical village which, despite its above-average homicide rate, never really loses its tranquillity or its innocence. Rereading the Golden Age novels with their confident morality, their lack of any empathy with the murderer and the popularity of their rural settings, readers can still enter nostalgically this settled and comfortable world. “Stands the church clock at ten to three?” And is there arsenic still for tea?

It was a tough case. Plenty of witnesses, but no one was talking.

4. Soft-centred and Hard-boiled

It was about eleven o’clock in the morning, mid-October, with the sun not shining and a look of hard wet rain in the clearness of the foothills… I was neat, clean, shaved and sober, and I didn’t care who knew it. I was everything the well-dressed private detective ought to be. I was calling on four million dollars.

Raymond Chandler , The Big Sleep

WHILE THE well-born and impeccably correct detectives of the Golden Age were courteously interviewing their suspects in the drawing rooms of country houses, the studies of rural clergymen and the rooms of Oxford academics, across the Atlantic crime writers were finding their material and inspiration in a very different society and writing about it in prose that was colloquial, vivid and memorable. Although this book is primarily about British detective novelists, the commonly described hard-boiled school of American fiction, rooted in a different continent and in a different literary tradition, has made such an important contribution to crime writing that to ignore its achievements would be seriously misleading. The two most famous innovators, Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler, have had a lasting influence beyond the crime genre, both in their own country and abroad.

No writer, whatever form his fiction takes, can distance himself entirely from the country, civilisation and century of which he is a part. A reader coming from Dashiell Hammett or Raymond Chandler to Agatha Christie or Dorothy L. Sayers could reasonably feel that these writers were living not only on different continents but in different centuries. So what England were these predominantly middle-class, well-educated novelists and their devoted readers portraying, what traditions, beliefs and prejudices were the purveyors of popular literature consciously or unconsciously reflecting?

As I was born in 1920 it was an England I knew, a cohesive world, overwhelmingly white and united by a common belief in a religious and moral code based on the Judeo-Christian inheritance-even if this belief was not invariably reflected in practice-and buttressed by social and political institutions which, although they might be criticised, attracted general allegiance, and were accepted as necessary to the well-being of the state: the monarchy, the Empire, the Church, the criminal justice system, the City, the ancient universities. It was an ordered society in which virtue was regarded as normal, crime an aberration, and in which there was small sympathy for the criminal; it was generally accepted that murderers, when convicted, would hang-although Agatha Christie, arch-purveyor of cosy reassurance, is careful not to emphasise this disagreeable fact or allow the dark shadow of the public hangman to fall upon her essentially comfortable pages. The death penalty is mentioned by Margery Allingham, and Dorothy L. Sayers in Busman’s Honeymoon actually has the temerity to confront Lord Peter Wimsey with the logical end to his detective activities, when he crouches weeping in his wife’s arms on the morning when Frank Crutchley hangs. Some readers may feel that, if he couldn’t face the inevitable outcome of his detective hobby, he should have confined himself to collecting first editions.

Читать дальше