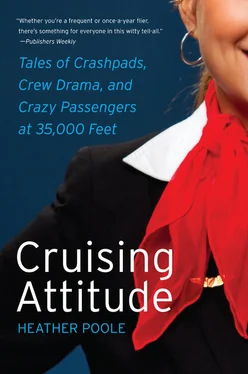

Falling asleep in class wasn’t the only way to obtain walking papers. Being late resulted in the same thing. This is why flight attendants have perfected the art of power walking. If for whatever reason we weren’t in our seats come class time, no matter how good the excuse, we were instructed to leave our training manuals beside the locked classroom door and immediately return to wherever we’d originally come from. None of us wanted to go back home. We were all here to fly away! But because the airplane doesn’t wait, neither would our instructors, who always smiled as they explained the dire consequences. I took notes. The way they treated us was an art form all to itself, and I figured the ability to be so politely condescending would come in handy at 30,000 feet. Or maybe it was 35,000 feet? I didn’t know for sure yet, but it wouldn’t be long before we’d all learn that cruising altitude depends on several factors, including weight of the aircraft, fuel, humidity, air temperature, winds, turbulence, and air traffic.

Given how crazy everything else at training seemed to be, I guess I shouldn’t have been so surprised when our food service procedure instructor turned to the chalkboard and started drawing out football plays. Well, it looked that way at first! Dumbfounded, we just sat in our seats staring at the board as he drew lines to represent aisles, boxes for carts, and arrows to show movement. And every plane seemed to have at least two different “plays” for us to memorize.

The way in which we were instructed to serve passengers depended first on the airplane. There are “two-class” and “three-class” flights, as well as three different services. A two-class flight has a first class and coach cabin. (Imagine two big boxes with several smaller boxes inside.) A three-class flight includes business class, but here’s where it gets confusing. A three-class flight might only provide a two-class service if the business-class seats have been sold as coach seats. It happens. (Two sets of three small boxes lined up side by side with six arrows pointing forward and back.) First class isn’t created equal, either. What a lot of passengers don’t realize is on most two-class flights, passengers get a business-class service in what is considered the first-class cabin. And while first-class service on a long-haul, three-class flight is exceptional, it often bears no resemblance, other than in name, to its counterpart on a two-class flight to Oklahoma City where the flying time is short and the ticket prices are cheap. (Five small boxes inside one big box. No arrows.)

Many smaller airlines only fly one type of aircraft, so their training, I imagine, is fairly simple. At my airline we work on all different kinds of airplanes, so we had to be trained on each one of them: F100, S80, 727, 757, 767, MD11, DC10, A300. We took on a new airplane every week. Each aircraft type is a completely different configuration in terms of number of passengers, lavatories, and galleys; the use and location of emergency and medical equipment; the operation of window and door exits; and how to command an evacuation. Over time an airline might retire its aging fleet and replace one type of aircraft with something newer. Flight attendants will then have to fly back to the academy on a day off to be trained. If flight attendants don’t get qualified on a particular aircraft, they are not allowed to work it. And because they’re unable to operate and command an evacuation if necessary, they are not considered “jump-seat qualified,” which means they will not be allowed to take a jump seat on a flight that’s full when they’re trying to use their travel passes to go on vacation or get to work.

Each aircraft galley is completely different when it comes to size and storage, so the type of plane affects the service. The 737 first-class galley is so small that a can of soda can’t stand up on the counter because an oven is located right over it. Some flight attendants might be inclined to pull out a cart, park it in front of the first-class entry door, and use the top as extra counter space. We didn’t learn this technique in training because the airline didn’t want us to block an exit, even in flight when it’s physically impossible to open the door. I don’t get it, either. The DC10 has the exact opposite problem. The airplane has a monster galley that first class, business, and coach all share. Carts are stored underneath the galley, so a flight attendant has to take a one-person elevator down to where the carts are kept and to spend the remainder of the flight sending up the correct cart at the appropriate time. You can imagine how popular this assignment is with new hires. Antisocial senior flight attendants love it.

The easiest way for a flight attendant to know which service to provide is to open up all the food carts and take a peek inside. A vegetable crudité after takeoff or salad toppings that include something other than a sprinkle of parmesan cheese and a choice of dressing is a sign it’s a true first-class service. But during training, when we finally got to practice what we’d learned on a mocked-up section of an airplane galley, the cart was empty! There was no way to guess the service when no food or beverage was allowed on the trainer. With only a single empty cart, an empty coffee pot (to serve both decaf and regular coffee, as well as tea), an insert of empty soda cans, and half a stack of plastic and Styrofoam cups to work with, I placed a real napkin down on a real tray table and asked a couple of classmates with opened flight manuals resting in their laps if they’d like something to drink. The instructors scribbled notes down on their clipboards as we made small talk while I served a pretend vodka tonic with a twist of pretend lime. Nobody complained about the service, or even the food! In our minds it tasted delicious.

On long-haul and international flights the service in the premium cabins is elaborate. There are predeparture drinks, appetizers, hot towels, salads, entrees, an assortment of breads and wines, desserts, and more. In first class, we were taught to use a three-tiered cart for amenities such as magazines and newspapers, as well as for salad and dessert delivery. Imagine my surprise to learn that our tiny drink carts at Sun Jet were really three-tiered dessert carts at other airlines. No wonder it had taken forever to do a service! It turned out that at a normal airline, the dainty silver cart was supposed to be accompanied with the “horse shoe” method for serving appetizers and desserts to first-class passengers. This meant we served one side of the first-class cabin, pulled the cart up, and then served the other side. Drinks and entrees were to be hand-delivered. In business class, drinks and entrees were also hand-delivered, while salads and desserts were to be served from a regular cart, not the three-tiered cart.

In coach, regular carts were used for everything. On most flights in coach, we were taught to move the carts forward-aft (front to back), but sometimes an aft-forward service worked best. That is until the aft-forward service was cut out altogether a year or two later—in coach. In first and business classes it still remains. The direction of the service depends on the flight number (even or odd) and the direction we’re flying (north-south or east-west). On shorter flights using larger aircraft, we learned to converge two carts if we wanted to finish the service. One cart would work aft-forward while the other worked forward-aft until they met in the middle in order to make the service quicker. (After 9/11 we stopped doing this, because having enough flight attendants on board to work two carts simultaneously in coach became so rare.) Then there were the “wide-body” (two-aisle) versus “narrow-body” (single-aisle) flights. On the wide-bodies—767s, MD11s, DC10s, and A300s—the instructors pounded into our brains that we must keep the carts as close together across the aisle from each other as possible. Not always an easy task to accomplish when some crew members were faster at serving than others.

Читать дальше