But in another way they had made all the difference. They had saved the honor of France, which was not just an abstraction but a living reality; you could hold your head up after the war and say, Some people didn’t submit, and that was true, too. They had acted with so much courage—courage for its own sake, courage because you could be courageous and couldn’t live with yourself without it—that they had supplied a kind of moral pattern for the rest of the century. Their fiction had become a feeling. Any country that could produce men and women as brave as Jacques Decour didn’t have to feel lost, or ashamed of itself. So it depends what you mean by difference, I said, and then I realized that it didn’t depend on what you meant by difference so much as on what you thought the big picture was.

Then, at Olivia’s insistence, I narrated, rather lamely, a history of the French Revolution, getting half of it wrong, but the essential point—that what started in glory ended in chaos, and what began in a declaration of all the rights of man ended in a denial of every one; but that the articulation of what was right was either no help at all or a constant source of hope—was there. It depends on how you see it. Brillat-Savarin’s eternal point was that at some level it didn’t matter, that the hubbub of the Palais Royal created a series of values—of which the restaurant we were sitting in now was a modest but real microcosm—that endured whatever squalid mess the politicians made of things, and that that was the right point to make.

How was the food? The food was fine. Sixty years ago it would have seemed very good. Seventy years ago, Decour’s time, it would have seemed like the best food in the world. We had filets of beef with green peppercorn sauce, and sautéed potatoes—they used to do pommes soufflées at these places, but no more, I know why—and green beans. The desserts were really good: Luke said that the profiteroles were the best he had ever had, and he is one who has eaten many profiteroles. I had an old classic, apple sorbet doused with Calvados, the kind of thing that is so hard to find these days. It was the kind of lunch Liebling writes about longingly from his New York of Schrafft’s and Longchamps and chicken à la king and pot pie (not that these are not good things in their way), and with the tastes of Barcelona still sharp on my lips—gingered scampi and smoked eel and brains—I knew that it was old-fashioned. Still, it was the fashion that I, too, had loved of old.

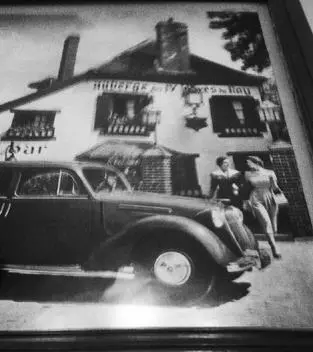

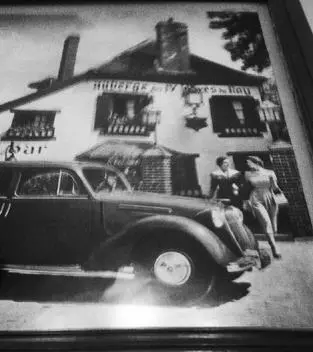

When lunch was ending with those good profiteroles and an extra glass of Calvados—Martha gave me the are-you-really-sure-about-that? look that I think they hand out, secretly, on the wedding day, to big eaters’ spouses—we explained why we had come, and Madame explained that yes, it was the same place, and yet it wasn’t the same place. That is, it was the same place—it had been the Auberge des IV Pavés du Roy for a half century, one could see the photographs of the old place inside—but when they had expanded the highway back in the early seventies, they had had to move it back some ways from the road. So though the same it was different and (one hoped) even better. They did have beautiful black-and-white photographs up inside, of the place as it had been back in the thirties. It had been very chic then for people to come out from Paris. Madame shrugged. (Here is one of those photographs, the auberge just as it was when Jacques Decour came here.)

In a way it was truer to the spirit of the adventure—righter—that it be the same and different, too. Food, after all, can’t be held in place. But the front is the same, and the place is, more or less, the same, and the town is the same, and the arrangement, tables inside, tables out in the garden, is the same.

Then Madame said, with real eagerness, “Did you find us on the Internet?” I could see that she hoped we did, with visions of Americans surfing the Web to this spot and crowding in for lunch. Martha told her the long story, eagerly—about Jacques Decour and the last letter and our search for him. It was well told, as by one oiled—not indecorously, just a little productively—by more red Sancerre than she is used to.

“Ah. So you didn’t find us on the Internet,” Madame said at last, disappointed a little. A lot. But then, being polite, she said she’d like a copy of whatever it is I was writing, which she shall have, whether she really wanted it or not.

I reread Decour’s last letter when we got home to Paris, and realized then that I had missed something essential. In a way, as Huck Finn would say, I missed the whole blame point, missed it a thousand miles. Decour was a communist, a Marxist, and buried in the letter is the clear cool claim that he is talking about food because he refuses to talk about God. Vous savez que je m’attendais depuis deux mois à ce qui m’arrive ce matin, aussi ai-je eu le temps de m’y préparer, mais comme je n’ai pas de religion, je n’ai pas sombré dans la méditation de la mort; je me considère un peu comme une feuille qui tombe de l’arbre pour faire du terreau. La qualité du terreau dépendra de celle des feuilles . “You know that I’ve been waiting for two months for what’s going to happen to me this morning, and that I have had time to prepare myself, but, as I have no religion, I have not fallen into a meditation on death; I consider myself a little as a leaf who falls from the tree to make the soil. The quality of the soil depends on that of the leaves.” It is a nonbeliever’s claim, quietly defiant. As I have no religion, I don’t think of death . The questions of food rise from that context.

Faith in history, not to mention in the Utopian state, has vanished, in various ways, noisy and silent, but the relation between the end of faith in Heaven and the assertion of faith in something else has not. The continuity of life is won in the face of time and tragedy, and the rituals of an inn in the country is one of the places that we locate it. We find it here. I don’t believe in a good God, and I don’t believe, as Decour must have, in History. But I believe in the inn of the four seasons: that Decour went there with the girl he loved, that he left her the menu when he knew the Nazis were going to kill him, that it has moved, and not moved, been rebuilt and is still the same, so that we can eat there now. They could walk in now, and be happy again in the garden. It would all be different but they would still be at home. We walked under the sign, and contemplated the connections. He had thought about that in his last moments. That the table came last to mind is another way in which the table always comes first.

Did I tell you that I found a photograph of him? Here he is. He looks terrifically elegant, doesn’t he? Oddly humorous, and he seems to be making a joke with his fork above those two bowls. What’s he doing, exactly? I think he may have a little bit of pasta in one bowl, and the sauce in the other—a French manner of eating pasta that I’ve often noticed, more controlled and precise than the Italian way. He’s certainly engaged in a small, sweet joke about eating, whatever the joke may be. I look at the picture often, and wonder. In his three-piece suit and neat parted hair, who could imagine that he would choose the fate he chose, and try to keep the pleasures of the table present in his mind even as he did? In any case there he is, and there we are, and whatever connection there may be, straight or crooked, occult or true, it passed across and around a table. For people who believe in this life alone, trying to decide how best to live, questions of food will always be of great importance.

Читать дальше