Adam Gopnik

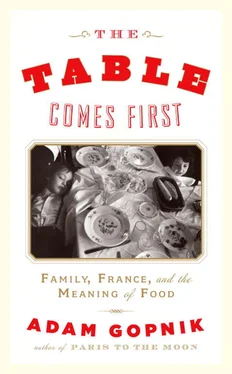

THE TABLE COMES FIRST

Family, France and the Meaning of Food

For Martha, Luke, and Olivia,

who set and share the nightly table…

and for Calvin Trillin, who set the standard

A cook a pure artist

Who moves everyman

At a deeper level than

Mozart, for the subject of the verb

To-hunger is never a name:

Dear Adam and Eve had different bottoms,

But the neotene who marches

Upright and can subtract reveals a belly

Like the serpent’s with the same

Vulnerable look. Jew, Gentile or pigmy,

He must get his calories

Before he can consider her profile or

His own, attack you or play chess,

And take what there is however hard to get down:

Then surely those in whose creed

God is edible may call a fine

Omelette a Christian deed.

The sin of Gluttony

Is ranked among the Deadly

Seven, but in murder mysteries

One can be sure the gourmet

Didn’t do it: children, brave warriors out of a job,

Can weigh pounds more than they should

And one can dislike having to kiss them yet,

Compared with the thin-lipped, they

Are seldom detestable. Some waiter grieves

For the worst dead bore to be a good

Trencherman, and no wonder chefs mature into

Choleric types, doomed to observe

Beauty peck at a master-dish, their one reward

To behold the mutually hostile

Mouth and eyes of a sinner married

At the first bite by a smile.

—W. H. AUDEN, “On Installing an American Kitchen in Lower Austria”

A Small Starter: Questions of Food

We have happy days, remember good dinners.

—CHARLES DARWIN

We eat to live? Yes, surely. But why then did the immortal gods also come to the table, and twice a day?

—LÉON ABRIC

IN THE early morning—six-forty, precisely—of May 24, 1942, a young professor of German, a resistant who had taken the underground name of Jacques Decour (his real name was Daniel Decourdemanche) and who taught before the war at the Lycée Henri IV in Paris, wrote a letter to his parents:

You know that for the past two months I have been expecting what is to happen to me this morning; so I have had the time to prepare myself for it; but since I have no religion, I have not given myself up to any meditation on death. Here are a few requests. I was able to send a word to the woman I love. If you see her—soon I hope—give her your affection. This is my dearest wish. I also wish that you could keep an eye on her parents who need help badly. Give them the things that are in my apartment and which belong to their daughter: The volume of the PLEIADE, THE FABLES DE LA FONTAINE, TRISTAN, LES QUATRE SAISONS, two water colors, the menu of the inn LES 4 PAVES DU ROY.

All these last days I have thought a lot about the good meals that we should have together when I was free. You will eat them without me, all the family together—but not sadly, please! I don’t want your thoughts to dwell on the good times that we might have had but on those that we really have shared. During these two months of solitude without even anything to read I have run over in my mind all my travels, all my experiences, all the meals that I have eaten. I even composed the outline of the novel. I had an excellent meal with Sylvain on the 17th. I have often thought of it with pleasure, as well as of the New Year’s supper with Pierre and Renée. Questions of food, you see, have taken on a great importance.

Three hours later, what was going to happen to Decour happened to him. He was shot by the Nazis in the courtyard of the prison. Yet there he was, in the last hours of his life, thinking about sending a menu from a little inn near Versailles to his girlfriend’s parents. (They must have eaten there, once.) His last thoughts turned to his best-loved meals. Of course, he’s nobly trying to ease the horror for his parents, but he’s also trying to find something to hang on to. Questions of food, you see, have taken on a great importance .

Questions of food seem to have taken on a great importance for us now, too. An obsessive interest in food is not a rich man’s indulgence, confined to catering schools and the marginal world of recipe books. Questions of food have become the proper preoccupation of whole classes and cable networks. More people talk about food now—why they eat what they eat and what you ought to eat, too—than have ever done before. Our food has become our medicine, our source of macho adventure, and sometimes, it almost seems, our messianic material. Good food, or watching it get made, anyway, has become, in the age of Rachael Ray and Food Network, a popular sport, and even the many who still prefer fast food to fancy or fresh get to prefer it loudly.

But if our own obsession (and the obesity it fathers) keeps increasing, its spirit seems at odds with that of Jacques Decour’s last thoughts. Not just the gravity, but the pathos of the feeling he evokes, and its humanity, seem very far from the questions we ask about food. We do feel a kinship to him beyond our pity at his end and our wonder at his courage. A kinship because his sense of food—of the rituals of the table, the memories of eating, even as the noise of our cross-talk and cable clatter increases—still shares in our own sense of what makes us human and what forms the core of our memories. For us, as for Jacques Decour, what makes a day into a happy day is often the presence of a good dinner. Though we don’t always acknowledge it enough, we still live the truth Darwin saw: food is the sensual pleasure that passes most readily into a social value.

Yet our questions of food are very different from Decour’s. We tend to argue about matters of taste, about the health of the planet, about the rights and wrongs of vegetarianism—all questions, finally, about what to eat. And we ask these questions expecting material answers: the right way to cook or eat. Decour’s questions are posed in a different key, one we can only call humanist: a view that life is a whole—that we can live fully, and that we ought to, with our pleasures as much as with our principles. He is talking about what goes on around the table as much as what’s on it. We can’t help feeling amazed at the sense of his letter but also a kind of unease, even a certain guilt, in his presence. Our questions of food, even the most high-minded, seem so small compared with his.

Why do we care so much about our food? There’s a sociological explanation (it’s a signal of status), a psychological explanation (it takes the place of sex), and a puritanical explanation (it’s the simplest sign of virtue). But all these, while worth pursuing, seem to be at one side of Decour’s questions. Thinking about questions of food an hour before his execution, Decour wasn’t thinking virtuous thoughts about his health, or even the planet’s health. Thinking about meals he was thinking about something else, about that inn near Versailles, about Sylvain and Pierre and Renée and about the parents who had raised and were now to lose him. Food represented for him the continuity of living, and what gave form to life.

Читать дальше