Heroism doesn’t always happen in a burst of glory. Sometimes small triumphs and large hearts change the course of history. Sometimes a chicken can save a man’s life.

1. SECOND SKIN

What to Wear to War

AN ARMY CHAPLAIN IS a man of the cloth, but which cloth? If he’s traveling with a field artillery unit, he is a man of moderately flame-resistant, insect-repellent rayon-nylon with 25 percent Kevlar for added durability. Inside a tank, he’s a man of Nomex—highly flame-resistant but too expensive for everyday wear. In the relative safety of a large base, the chaplain is a man of 50/50 nylon-cotton—the cloth of the basic Army Combat Uniform, as well as the camouflage-print vestments that hang in the chaplain’s office here at Natick Labs.

The full and formal title of the complex of labs known casually as “Natick” is US Army Natick Soldier Research, Development and Engineering Center. Everything a soldier wears, eats, sleeps on, or lives in is developed or at least tested here. That has included, over the years and through the various incarnations of this place: self-heating parkas, freeze-dried coffee, Gore-Tex, Kevlar, permethrin, concealable body armor, synthetic goose down, recombinant spider silk, restructured steaks, radappertized ham, and an emergency ration chocolate bar with a dash of kerosene to prevent ad libitum snacking. Natick chaplains, for their part, have devised portable confessionals, containerized chapels, and extended shelf life [3] Natick Labs and precursor the Quartermaster Subsistence Research Laboratory have extended shelf lives to near immortality. They currently make a sandwich that keeps for three years. Meat, in particular, has come a long way since the Revolutionary and Civil wars, when beef came fresh off cattle driven alongside the troops. During World War II, the aptly named subsistence lab developed partly hydrogenated, no-melt “war lard” and heavily salted and cured, extra-dry “war hams” that kept for six months without refrigeration and earned the not exactly over-the-moon descriptors “palatable and satisfactory.” I quote there the July–August 1943 Breeder’s Gazette , sister publication of the Poultry Tribune , a newspaper either about or for barnyard fowl.

communion wafers.

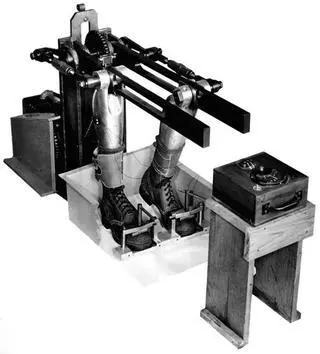

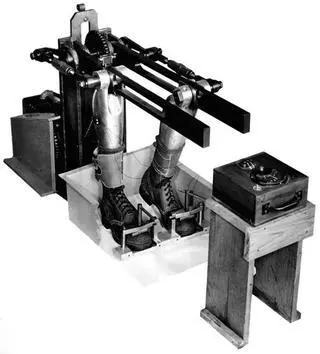

It’s a balmy 68 degrees at Natick this afternoon. It may, at the same time, be 70 below zero with horizontally blown snow or 110 in the shade, depending on what’s being tested over in the Doriot. The Doriot Climatic Chambers were the centerpiece of the complex when it opened in 1954. Never again would troops be sent to the Aleutian Islands with seeping, uninsulated boots or to equatorial jungles with no mildew-proofing on their tents. Soldiers fight on their stomachs, but also on their toes and fingers and a decent night’s sleep.

These days, the snow and rain machines are rented out to L.L. Bean or Cabela’s as often as they’re used to test military outerwear. Repelling the elements is the least of what the US Army needs its uniforms to do. If possible, the army would like to dress its men and women in uniforms that protect them against all that modern warfare has to throw at them: flames, explosives, bullets, lasers, bomb-blasted dirt, blister agents, anthrax, sand fleas. They would like these same uniforms to keep soldiers cool and dry in extreme heat, to stand up to the ruthless rigors of the Army field laundry, to feel good against the skin, to look smart, and to come in under budget. It might be easier to resolve the conflicts in the Middle East.

LET US begin at Building 110, which is what everyone calls it. Officially it was christened the Ouellette [4] Misspelled as “Uoellette” on the Natick Building Inventory, and “Oullette” on the sign outside the building. Somebody burned for that one.

Thermal Test Facility, lending a flirtatious French flair to lethal explosions and disfiguring burns. The head textile technologist is a slim, classy, fiftyish woman of fine-grained good looks, dressed today in a cream-colored cable-knit wool tunic. I took her to be the Ouellette, and then she opened her mouth to speak and a hammered-flat Boston accent flew out and slammed into my ear. She is an Auerbach, Margaret Auerbach, but around 110 she’s just Peggy, or “flame goddess.”

When someone in industry thinks they’ve built a better flame-resistant fabric, a sample comes to Auerbach for testing. Some people submit swatches; others optimistically ship off whole bolts. Their hopes may be undone by a single strand of thread. “To see what our guys might be inhaling,” Auerbach heats a few centimeters of thread to around 1500 degrees Fahrenheit. The fumes produced by this are identified by gas chromatography. Flame-resistant textiles—some, anyway—work via heat-released chemicals. Auerbach needs to be sure the chemicals aren’t more dangerous than the flames themselves.

Once it’s established that the textile is nontoxic, Auerbach sets about testing its flame-stopping mettle. This is done in part with a Big Scary Laser (as the sticker on its side reads). Auerbach places a swatch in the laser’s sights. And here is the best part: To activate this laser, you push a giant red button . The beam is calibrated to deliver a scaled-down burst of energy representative of an insurgent’s bomb—a teacup IED. A sensor behind the swatch measures the heat passing through, yielding a figure for how much protection the fabric provides and what degree burn would result.

Auerbach switches on a vacuum pump that sucks the swatch tight against the sensor. This is done to approximate an explosion’s pressure wave—the dense pileup of accelerated air that can knock a person flat. More subtly, it forces clothing flush against the skin, which can heighten the heat transfer and worsen the burn. One of the winning attributes of Defender M, the textile of the current Flame Resistant Army Combat Uniform, or FR ACU (“the guys call it ‘frack you’”), is that it balloons away from the body as it burns.

The downside to Defender M has been that it tears easily. (They’re working on this.) The same thing that keeps it comfortable in hot weather also makes it weaker; it’s mostly rayon, which draws moisture but has low “wet strength.” If a garment tears open in the chaos of an explosion, now the protective thermal barrier is gone. Now you’re toast. The manufacturer throws a little Kevlar in, but it still isn’t as strong as Nomex, a fiber often used for firefighter uniforms. Nomex also has superior flame resistance: It buys you at least five seconds before your clothes ignite.

Auerbach explains that this is especially important for crews inside tanks and aircraft. “Where they can’t roll, drop, and…” She rewinds. “Drop, stop… what is it?”

“Stop, drop, and roll?”

“Thank you.”

Why not make all army uniforms out of Nomex? Poor moisture management. Not the best choice for troops running around sweating in the Middle East. And Nomex is expensive. And difficult to print with camouflage.

This is how it goes with protective textiles: Everything is a trade-off. Everything is a problem. Even the color. Darker colors reflect less heat; they absorb and transfer more of it to the skin. Auerbach goes across the lab to get a swatch of camouflage print cloth. She points to a black area. “You can see this has a pucker where it was absorbing more heat.”

“It has a what?” I heard her, but I need to hear her say pucka again. The fabulous Boston accent.

I would have guessed the military to be a fan of polyester: strong, cheap, doesn’t ignite. The problem is that it melts and, like wax and other melted items, it drips and sticks to nearby surfaces, thereby prolonging the contact time and worsening the burn. What you really don’t want to be wearing inside a burning army tank is polyester tights. [5] I went on the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System to find you a figure for the number of burns caused each year by pantyhose. Alas, NEISS doesn’t break clothing injuries down by specific garment. I skimmed “thermal burns, daywear” until I ran out of patience, somewhere around the thirty-seven-year-old man who tried to iron his pants while wearing them.

Читать дальше