Robert Leckie - Strong Men Armed

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Leckie - Strong Men Armed» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: Cambridge, Год выпуска: 2010, ISBN: 2010, Издательство: Da Capo Press, Жанр: nonf_military, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Strong Men Armed

- Автор:

- Издательство:Da Capo Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- Город:Cambridge

- ISBN:978-0-786-74832-7

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Strong Men Armed: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Strong Men Armed»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Strong Men Armed — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Strong Men Armed», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“All right,” said a young lieutenant aboard one troopship, “if a Jap jumped from a tree what would you do?”

“Kick him in the balls!” came the answer, almost in concert, and the lieutenant grinned and dismissed his class.

Below decks, many other Marines had joined the sailors in preparing the ships for battle. They sweated in stuffy supply holds, often straining their heads aloft to the open hatches while winches swung the heavy hooks and cargo nets among them, sometimes cursing when beads of sweat which had formed on their eyebrows fell into their eyes, blinding them. Men could be badly hurt by swinging hooks, and one Marine had already been killed by them.

Above the whining of the winches rose the spluttering roar of landing-boat motors being started. Their coxswains were testing them, even as they were being freed of their lashings and swung out on davits. Brassy-voiced bosun’s mates shouted at their men, and the harder the sailors worked, the louder the bosun’s mates yelled—for it is characteristic of their calling that they sweat only about the mouth.

On the artillery transports, boxes of shells were lifted on deck and placed in readiness to go over the side next day. Seventy-five- or 105-millimeter howitzers were trundled to the gunwales and coils of rope for hauling them inland were looped about their barrels. Winchmen on the assault transports hauled boxes of rifle ammunition, mortar shells, spare gun parts and roll after roll of barbed wire on deck.

So much barbed wire puzzled the men. It was defensive warfare material, and they, as they thought, were strictly offensive troops. Once they had seized Guadalcanal, they would turn it over to a garrison of soldiers and move on to assault another island. So they had been told, and the great stores of barbed wire bewildered them almost as much as the outlandish nature of the island they were to capture.

“Who ever heard of Guadalcanal?” one of them growled. “Whadda we want with a place nobody ever heard of before?”

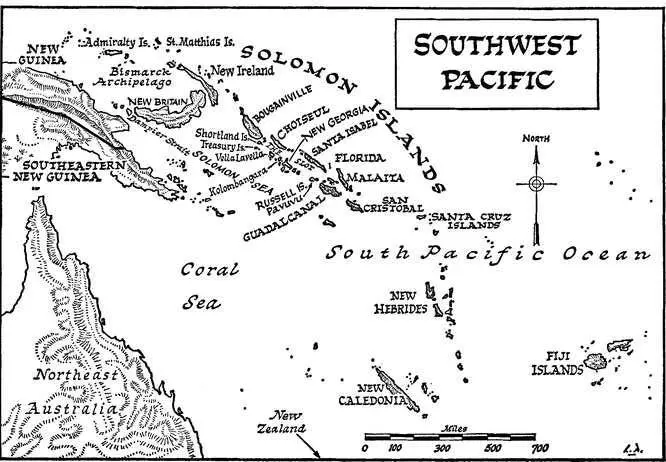

It was a common complaint, and it had been raised since July 31 when the troopships had made rendezvous with the warships off the Fijis and the men had been informed of their destination. They had been startled, but their surprise had far from rivaled the astonishment of their commander, Major General Alexander Vandegrift, when he, too, had been abruptly made aware that he was going to Guadalcanal.

When Vandegrift had come to Auckland in New Zealand on June 26, his First Marine Division had already been fragmented by the problem of moving men and munitions across the vast reaches of the Pacific. His Seventh Regiment had been detached from his command and sent to Samoa. His Fifth Regiment was encamped outside the New Zealand capital of Wellington, his First Regiment was sailing from San Francisco for Wellington, the Third Defense Battalion assigned to his division was in Pearl Harbor, his Eleventh Regiment of artillery was divided among these fragments, along with other supporting troops, and the Second Regiment, which would be detached from the Second Marine Division to replace Vandegrift’s missing Seventh, was in San Diego Harbor. More gravely, not half the men in this division had been a year in uniform. They were mostly boys in their late teens and early twenties. Though they were high-hearted volunteers, tough and sturdy youths who had flocked to the Marines in the weeks following Pearl Harbor, they were still barely better than “boots.” Some had been with their units only a week before departure from New River, North Carolina. They were in great need of training, for all their zest and bounce. So were their junior officers, those “Ninety-Day Wonders” just out of the Officer Candidates School in Quantico. Many of the senior NCO’s and officers at company and even battalion level were reservists, men who had trained in armories one night a month and spent an annual two weeks in summer camp. But the division was heavily salted with seasoned NCO’s, as well as with many of the battle-blooded officers in the Marine Corps. With these-and with six months’ grace—Vandegrift was confident that he could field a fine fighting force in early 1943.

In this mood of confidence, Vandegrift came to Auckland and sat at a table across from Vice Admiral Robert Ghormley, commander of the South Pacific Area. Ghormley handed him a dispatch from America’s supreme command, the Joint Chiefs of Staff. It said:

Occupy and defend Tulagi and adjacent positions (Guadalcanal and Florida Islands and the Santa Cruz Islands) in order to deny these areas to the enemy and to provide United States bases in preparation for further offensive action.

Vandegrift read, deeply interested. Perhaps, when this base was assaulted and secured, he would be able to train his division there.

“Who will do the occupying?” asked the general.

“You,” said the admiral.

There was an interval, and then:

“When?”

“The first of August.”

If Alexander Vandegrift had glanced at his watch, he could not have been exaggerating the urgency of that moment. August 1! Between the present date and August 1 were thirty-seven days. But it would take six days to sail from New Zealand to the Fiji rendezvous area, and it would take another seven days to sail from the Fijis to the objective in the Solomons. That left twenty-four days in which to await the arrival of troops from California and Hawaii, to reconnoiter the objective, to study its terrain and map it, to get Intelligence working at an estimate of probable enemy defenses and troop strength, to load 31 transports and cargo carriers with 19,000 men and 60 days’ combat supply—and then to conduct joint rehearsals before the day of assault. Twenty-four times twenty-four hours to go, and there was not even a battle plan begun. There was not a scrap of information on the objective beyond a Navy hydro-graphic chart made thirty-two years ago and Jack London’s short story The Red One, which, though set in Guadalcanal, was already suspect by spelling it Guadalcana r . If General Vandegrift had been asked to land his Marines upon the moon, he could not have had less knowledge of the battleground.

But Vandegrift was a Marine accustomed to adversity and skilled in the art of improvising. In those years between World Wars, when Congress slashed military budgets with a belligerence matched only by the ferocity of its pacifism, he had been among those officers who fought to fulfill a vision of the Marine Corps as a highly trained assault force with a special mission of making ship-to-shore landings on enemy-held terrain. To such professionals, the seeming setback was the normal condition of career. And Vandegrift was a professional, a soft-spoken, tough-minded commander in the mold of Stonewall Jackson. Intelligent enough to be appalled by the task confronting him, sensible enough to mask that dismay before his staff, he set that staff to work at organizing America’s first full-scale amphibious invasion—imparting to them some of his own sense of urgency that was the surest guarantor of unpleasant surprise.

It was a surprise to find that the totality of the war did not impress the Wellington longshoremen’s union controlling work on the huge Aotea Quay provided by the New Zealand government. The union still believed that the longer a job takes the longer the pay lasts. All cries for speed elicited the scornful rejoinder “Not half!”—and the unloading of ships moved at a crawl. So the union was ignored and the Marines were used as dock-wallopers. Enormous working parties of 300 men each were placed on around-the-clock shifts, unloading and loading their own ships. For the problem was one of unloading as well as loading.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Strong Men Armed»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Strong Men Armed» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Strong Men Armed» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.