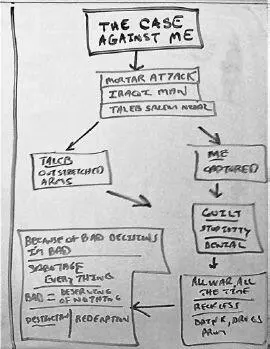

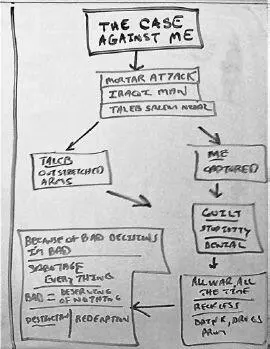

“The Case Against Me” schematic on dry-erase board

Number One starts in northern Afghanistan with a simple hesitation. It’s October 2001 on a hill in an area near the border with Tajikistan known as Pul-i-Khomri. It’s a place in which deep trench lines, reminiscent of World War I, separate the ruling Afghan Taliban forces from the Northern Alliance fighters seeking to oust them. The two sides are casually tossing mortars back and forth, taunting each other on the same radio frequency as if they were engaged in nothing more deadly than a backyard game of badminton. I’m on a mound of dirt topped with a Russian-made T-62 tank left over from the Soviet invasion, with a few journalist colleagues. We’re talking and laughing at the absurdity of it all until we hear a crack in the distance. The tank commander is peering at the Taliban lines through my spotting scope, which I bought for a few dollars at a street market in the Uzbek capital of Tashkent two weeks back on my way into Afghanistan. Through my video camera’s viewfinder, I watch him drop the scope and dive behind the tank. The ground shakes as the mortar round explodes thirty feet behind us. Bounding shrapnel tears into the thigh and glutes of a producer for National Geographic who’s standing on my left, just inches away from me. He goes down. “I’m hit, I’m hit,” he says, grabbing his leg in pain. I’ve been recording video the entire time, including the last shell impact. I swing my camera over to the producer and the blood is now seeping through his hands as he holds them against the wounds. It’s dramatic and rare footage, a seldom-captured incoming round and its casualty, the ultimate cause and effect. I know our news audience does not see this kind of thing very often. It’s remarkable and, in my mind, instructive in an obvious way. This is what really happens when hard metal meets soft flesh. I shout to the others to take cover on the other side of the tank since the Taliban will discover through their own spotting scopes that they’ve got this site dialed in. But this is just the beginning of my dilemma. As a journalist I don’t want to stop shooting, even while the producer bleeds. If the shrapnel has penetrated his leg’s femoral artery, one of the body’s largest, he will bleed out in less than four minutes unless something is done. I continue to shoot. He even prompts his own videographer, whose camera missed everything: “Hey, shoot this,” he says, still holding his leg. I feel the strange tug of something at my shirttail while I continue to roll. It’s light but insistent, probably just my conscience. I want to ignore it, but finally and with reluctance, I put the camera on the dirt next to the wounded producer but leave it on record. My own adrenaline is pumping as I begin to realize that I’m lucky to be alive myself, given the producer’s proximity to me. In fact, if he hadn’t been standing where he was to absorb the flying shards of metal, I might be the one bleeding now instead. “Give me the fucking scarf,” I say, amped by adrenaline. Pulling it from his neck, I wind it around his thigh several times and then tie it off tightly above the bleed. I pick up the camera when I’m done, point it at him and ask how it feels to have been hit with a mortar round. “It’s like a tornado that has torn through my leg,” he says. It’s only later in recounting the story that I realize, I didn’t choose him over the shot. I chose both. He will live and even bask in some media attention in the immediate aftermath, but I wonder if the same would be true if the shrapnel had hit the artery and I still hesitated before wrapping the wound to make sure I got my shot.

In the case against me, Number Two begins with this question: “Are you going to videotape me if I shoot him?” It’s November 2004. I’m following two Marines through the streets of Fallujah during the first day of the ground offensive to take back the city from insurgents. It’s called Operation Phantom Fury, but so far, with the exception of a few bodies here and there, there don’t seem to be many insurgents left. But as we come into an opening between buildings, I see an older Iraqi man lying on the ground, a close-cropped white beard in stark contrast to the maroon stream of blood running in a little channel from his head to the curb. His shirt is open, exposing a white T-shirt underneath and a chest that is rising and falling in what seem to be agonal breaths, likely his last. His right hand rests on his chest, while the left arm is bent at the elbow and pointing up, the hand cupped open, weirdly reminiscent of the queen of England’s wave. I move closer to see the extent of his injuries but reel back when I see that the right side of his head is missing. While he looked complete from a distance, a Marine sniper had fired a round through his eyeball, taking much of his skull and brain through the exit wound in the back. Yet, it seems so oddly clean, almost surgical. After I walk back over to the Marines, one of them asks me the question, “Are you going to videotape me if I shoot him?” I don’t think there’s any malice behind the question. It’s a mercy killing, I’m nearly certain. I respond almost automatically: “Of course I am, that’s my job,” I say, but as the words come out of my mouth, I’m wondering why I can’t just let the Marine finish the job without videotaping it. Doubtless, the man is going to die. Why not let it be without more suffering? The Marine shrugs, tells the other something along the lines of it’s not worth the risk of getting into trouble—“The guy’s going to die anyway.” The two of them walk on and leave me alone with the Iraqi man with half a head missing. I look at him. He’s still breathing, still bleeding. What’s left of his life is in my hands now. I wonder if this is the worst way to die, alone with no one who can even understand your last words, if you have any. I wonder if I should’ve let the Marine shoot him. I don’t know if he’s suffering terribly or if that sniper’s bullet removed any sense of pain or awareness along with that part of his head. I wonder how I became the final arbiter of the last moments of his existence. I look at him again and realize we are alone in this place together. The Marines are gone; there’s no one else around. This Iraqi man, dressed in civilian clothes, most likely in his mid to late fifties, has no weapon by his side and perhaps never did. He is almost certainly someone’s father, maybe even a grandfather, but there’s no one around him now, only me. He will die lying on the ground as a stranger holding a video camera looks over him. But I can’t let that happen. It’s just not right. So here is what I do instead: I walk away. I follow the path of the Marines and let him breathe his last breath alone in the street. The twinge of guilt I felt disappeared once the shooting started again, just around the corner. I left the half-headed man behind… or so I thought.

That should be enough, but it’s not. Number Three is the most egregious thing I have ever done in my life: I walked away again, but this time from a man very much alive and pleading with me to help him. When I left the room he was murdered.

Taleb Salem Nidal, the man who was murdered after I failed to help him

Taleb Salem Nidal was one of five wounded Iraqi insurgents who had been captured by U.S. Marines after a confused engagement in a Fallujah mosque. The fighting took place during one of the biggest and bloodiest American-led military operations since the Vietnam War, Operation Phantom Fury. In November 2004, more than thirteen thousand American, British and Iraqi government troops took up positions north of the city, poised to push south, flushing out and killing the insurgents who had controlled Fallujah for months. Nidal was holed up with more than a dozen other fighters inside a mosque in south Fallujah. A week into the battle, Marines reached the mosque and after taking fire, hit back hard. (The early stages of this engagement are detailed in chapter 1.) When the smoke finally cleared, ten of the insurgents were dead and five injured.

Читать дальше