While the obstacles in gathering the material for this book and deciding what, if any, purpose it would serve were substantial, I decided that society as well as the soldiers would be better off for the telling and the knowing . I came to this conclusion after pondering my own experiences as well as a voluminous amount of clinical and anecdotal research about soldiers reentering their home societies. Most of it indicated the following: When a soldier decides not to share his life-defining moments in war with his wife, parents, children or community because of the accompanying guilt, shame, pain or any other valid reason, it increases the likelihood that he will feel more alienated from the society for which he was fighting, possibly to a debilitating degree. The alcohol, drugs and other self-medicating outlets for soldiers dealing with PTSD further isolate him from the normal comforts of a peacetime existence, work, family and friendships, and force him even deeper into the margins of society. Also, without the demythologized, demystified, authentic experiences of war being shared by those most directly involved in it, society itself will remain ignorant of the real practice of war, its costs and consequences.

A society “protected” from the reality of war can rewrite the narrative, shaping and forming it into something less terrible and costly by emphasizing only the heroism and triumphs rather than the dark, ugly deeds that occur with much greater frequency than we care to imagine or discuss.

More positively, the warrior who does share the descriptive and often disturbing narrative of his own war experiences reconnects himself to his community while simultaneously reminding them of the responsibilities that they also bear for his actions by sending him to fight and kill on their behalf. It’s rarely an easy message to hear but it’s essential to the positive evolution and enlightenment of the postconflict society. As Tick writes in War and the Soul , “Our society must accept responsibility for its warmaking. To the returning veterans, our leaders and people must say, ‘you did this in our name and because you were subject to our orders, we lift the burden of your actions from you and take it onto our shoulders. We are responsible for you, for what you did and the consequences.”

Stories are a way for societies to share in the burden of war. They provide knowledge necessary to better understand the warrior’s experience and help them find meaning and sometimes forgiveness for their actions. Warriors, I’ve learned, become collateral damage too, killing a little of their own humanity every time they must pull the trigger, even though they do so at our bidding.

Tim O’Brien wrote so eloquently, in his classic Vietnam War novel The Things They Carried , “A true war story is never moral. It does not instruct, nor encourage virtue, nor suggest models of proper human behavior, nor restrain men from doing the things men have always done. If a story seems moral do not believe it.”

My goal here is to try to tell the true war stories, not moral ones. The ones found here are entertaining, horrifying, brutally funny and banal, like so many other experiences. But because they involve war, they bring their own insistent drama that comes with the acts of fatal violence. The warriors brave enough to share them have already lived these stories. Now the communities they fought for need to honestly hear them, wherever they may lead.

As I mentioned, I sought out soldiers and Marines I knew and had reported on in the past, but I also found others, including those in the military service of other nations. I found them through veteran’s groups, military associations and even medical and mental health professionals. This resulted in a broad base of interviews, providing a sampling of war experiences that ran the gamut from monstrous to mundane. Only a few made it into this book, primarily because I felt either the subjects were the most candid or their individual stories were the most instructive. Regardless, for all kind enough to share, the very act of their participation gave me hope that we may eventually see through the smoky glass of myth, parable and revisionism to something that resembles the ground truth .

On that point, these stories are recollections, oral histories from the perspectives of the men and women telling the stories. Like all who remember, they will remember imperfectly, with omissions and additions and perhaps lost players and parts. These are not after-action reports or official historical accounts, but the kind of stories that are true to their tellers and imbued with their own perspectives and even judgments. In fact, the primary sources in them are the individuals profiled. It was, after all, their perspective as combatants that I was seeking. They are difficult stories all, and I’m both grateful and hopeful that these acts of sharing will help bring these soldiers, and those who surround them, some peace. And as we see the war in Iraq ending and the Afghan war winding down, our communities will be filled with returning veterans carrying the physical and psychological burdens of their war experiences. We must hurry, using mostly our ears and hearts, to lighten the load.

Now the war is over, my war charms lie abandoned in my bedroom, leaving me with death on my shoulder and a monkey on my back. Peace seems to allow little space for belief in destiny, fate, God or ghosts.

—Anthony Loyd,

My War Gone By, I Miss It So

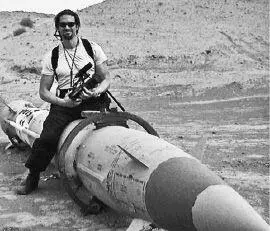

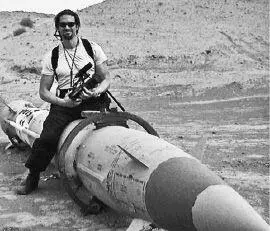

The author sitting on an Iraqi antiaircraft missile (2003)

Here’s what happens when you come home from war: the overload of excitement, intensity, absurdity, poignancy, foolishness, depth, danger, frivolity, importance and delicious single-mindedness comes to a screeching halt. You’ve been transformed through months of overstimulation fueled by violence and the threat of it. I once believed this was a fate only for the prosecutors of war and its victims, not for those simply bearing witness. I was wrong. In war, there are no sidelines on which to sit.

War’s most cunning trick, it seemed, was the war it seeded within me. I wanted to cling to the concept of my own goodness, but the choices I had made during war seemed to indicate something else entirely: a man who was at best oblivious and at worst heartless. It was that “Jungian thing” again, Private Joker pondering the “duality of man.” For years, this confrontation for a dominant truth where none existed left me veering between wanting to be alone and never wanting to be alone, deliberate isolation and self-medicating social inebriation. Neither was a very good long-term companion.

But during my research I came across this quote by Virginia Woolf: “If you do not tell the truth about yourself you cannot tell it about other people.” It resonated with me deeply. I knew I needed to tell the truth about myself to be able to do the same about others. But to do so, I first needed to learn the truth: was I a good man simply making bad choices, or had war simply stripped away that façade and revealed my dark character? I began my examination using a dry-erase board to sketch out the “case against me.” Even as a schematic, the evidence for the latter appeared daunting. When I was done, it looked like this on the opposite page.

The case rests on three separate events that occurred in the last decade, in which I covered war almost exclusively. In general, these events represent the moral dilemmas that war poses for everyone exposed to it, even noncombatants like me. But specifically they are an ascending scale of defining moments representing the destructive and redemptive opportunities in the narrative of my own life. There were times when I wished and believed that the guilt from my choices would destroy me. There are times when I’m convinced that my life would have little significance without these events. Regardless, they are mine and I must account for them. In their full explanations they may sound reasonable, but they sometimes feel like the popgun rantings of a soul in full disequilibrium.

Читать дальше