Evan Wright

GENERATION KILL

TO THE WARRIORS OF HITMAN-2 AND HITMAN-3:

The strength of the Pack is the Wolf.

°

Because the U.S. Military has partially embraced a conversion to the metric system, Marines measure distances in meters and kilometers, but still use inches and feet and speak of driving in “miles per hour.” My account of the invasion retains these inconsistencies, switching between the metric and English systems as the troops did. Keeping track of this is simple: A meter (which equals 39.3 inches) is roughly 10 percent longer than a yard, and a kilometer (which equals 0.6 mile) is just over half a mile.

Some men are identified in this book solely by the nicknames awarded to them by fellow Marines.

°

IT’S ANOTHER IRAQI TOWN, nameless to the Marines racing down the main drag in Humvees, blowing it to pieces. We’re flanked on both sides by a jumble of walled, two-story mud-brick buildings, with Iraqi gunmen concealed behind windows, on rooftops and in alleyways, shooting at us with machine guns, AK rifles and the odd rocket-propelled grenade (RPG). Though it’s nearly five in the afternoon, a sandstorm has plunged the town into a hellish twilight of murky red dust. Winds howl at fifty miles per hour. The town stinks. Sewers, shattered from a Marine artillery bombardment that ceased moments before we entered, have overflowed, filling the streets with lagoons of human excrement. Flames and smoke pour out of holes blasted through walls of homes and apartment blocks by the Marines’ heavy weapons. Bullets, bricks, chunks of buildings, pieces of blown-up light poles and shattered donkey carts splash into the flooded road ahead.

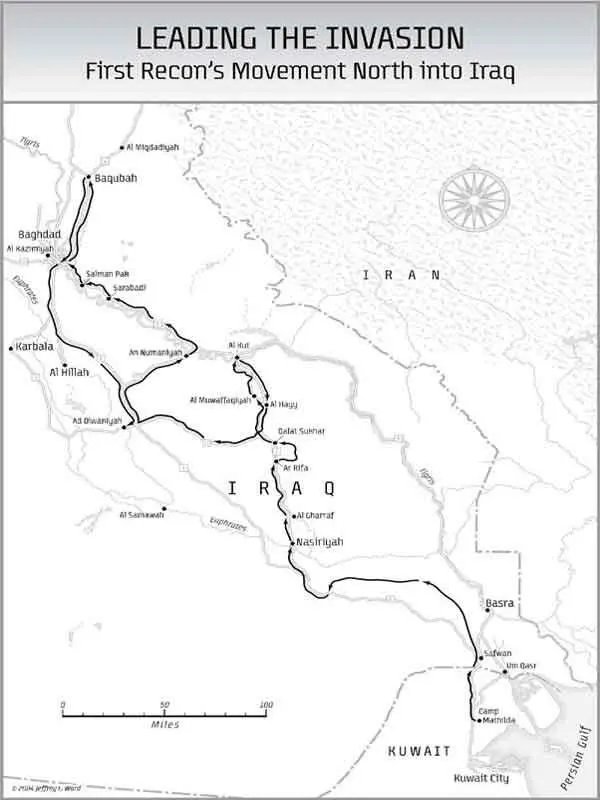

The ambush started when the lead vehicle of Second Platoon—the one I ride in—rounded the first corner into the town. There was a mosque on the left, with a brilliant, cobalt-blue dome. Across from this, in the upper window of a three-story building, a machine gun had opened up. Nearly two dozen rounds ripped into our Humvee almost immediately. Nobody was hit; none of the Marines panicked. They responded by speeding into the gunfire and attacking with their weapons. The four Marines crammed into this Humvee—among the first American troops to cross the border into Iraq—had spent the past week wired on a combination of caffeine, sleep deprivation, tedium and anticipation. For some of them, rolling into an ambush was almost an answered prayer.

Their war began several days ago, as a series of explosions that rumbled across the Kuwaiti desert beginning at about five in the morning of March 20. The Marines, who had been sleeping in holes dug into the sand twenty kilometers south of the border with Iraq, sat up and gazed into the empty expanse, their faces blank as they listened to the distant thundering. They had eagerly awaited the start of war since leaving their base at Camp Pendleton, California, more than six weeks earlier. Spirits couldn’t have been higher. Later, when a pair of Cobra helicopter gunships thumped overhead, flying north, presumably on their way to battle, Marines pumped their fists in the air and screamed, “Yeah! Get some!”

Get some! is the unofficial Marine Corps cheer. It’s shouted when a brother Marine is struggling to beat his personal best in a fitness run. It punctuates stories told at night about getting laid in whorehouses in Thailand and Australia. It’s the cry of exhilaration after firing a burst from a .50-caliber machine gun. Get some! expresses, in two simple words, the excitement, the fear, the feelings of power and the erotic-tinged thrill that come from confronting the extreme physical and emotional challenges posed by death, which is, of course, what war is all about. Nearly every Marine I’ve met is hoping this war with Iraq will be his chance to get some.

Marines call exaggerated displays of enthusiasm—from shouting Get some! to waving American flags to covering their bodies with Marine Corps tattoos—“moto.” You won’t ever catch Sergeant Brad Colbert, the twenty-eight-year-old commander of the vehicle I ride in, engaging in any moto displays. They call Colbert “The Iceman.” Wiry and fair-haired, he makes sarcastic pronouncements in a nasal whine that sounds like comedian David Spade. Though he considers himself a “Marine Corps killer,” he’s also a nerd who listens to Barry Manilow, Air Supply and practically all the music of the 1980s except rap. He is passionate about gadgets: He collects vintage video-game consoles and wears a massive wristwatch that can only properly be “configured” by plugging it into his PC. He is the last guy you would picture at the tip of the spear of the invasion forces in Iraq.

Now, in the midst of this ambush in a nameless town, Colbert appears utterly calm. He leans out his window in front of me, methodically pumping grenades into nearby buildings with his rifle launcher. The Humvee rocks rhythmically as the main gun on the roof turret, operated by a twenty-three-year-old corporal, thumps out explosive rounds into buildings along the street. The vehicle’s machine gunner, a nineteen-year-old Marine who sits to my left, blazes up the town, firing through his window like a drive-by shooter. Nobody speaks.

The fact that the enemy in this town has succeeded in shutting up the driver of this vehicle, Corporal Josh Ray Person, is no mean feat. A twenty-two-year-old from Missouri with a faintly hick accent and a shock of white-blond hair covering his wide, squarish head—his blue eyes are so far apart Marines call him “Hammerhead” or “Goldfish”—Person plans to be a rock star when he gets out of the Corps. The first night of the invasion, he had crossed the Iraqi border, simultaneously entertaining and annoying his fellow Marines by screeching out mocking versions of Avril Lavigne songs. Tweaking on a mix of chewing tobacco, instant coffee crystals, which he consumes dry by the mouthful, and over-the-counter stimulants like ephedra-based Ripped Fuel, Person never stops jabbering. Already he’s reached a profound conclusion about this campaign: that the battlefield that is Iraq is filled with “fucking retards.” There’s the retard commander in the battalion, who took a wrong turn near the border, delaying the invasion by at least an hour. There’s another officer, a classic retard, who has spent much of the campaign chasing through the desert to pick up souvenirs—helmets, Republican Guard caps and rifles—thrown down by fleeing Iraqi soldiers. There are the hopeless retards in the battalion-support sections who screwed up the radios and didn’t bring enough batteries to operate the Marines’ thermal-imaging devices. But in Person’s eyes, one retard reigns supreme: Saddam Hussein. “We already kicked his ass once,” he says. “Then we let him go, and he spends the next twelve years pissing us off even more. We don’t want to be in this shithole country. We don’t want to invade it. What a fucking retard.”

Now, as enemy gunfire tears into the Humvee, Person hunches purposefully over the wheel and drives. The lives of everyone depend on him. If he’s injured or killed and the Humvee stops, even for a moment in this hostile town, odds are good that everyone will be wiped out, not just the Marines in this vehicle, but the nineteen others in the rest of the platoon following behind in their Humvees. There’s no air support from attack jets or helicopters because of the raging sandstorm. The street is filled with rubble, much of it from buildings knocked down by the Marines’ heavy weapons. We nearly slam into a blown-up car partially blocking the street. Ambushers drop cables from rooftops, trying to decapitate or knock down the Humvee’s turret gunner. Person zigzags and brakes as the cables scrape across the Humvee, one of them striking the turret gunner who pounds on the roof, shouting, “I’m okay!”

Читать дальше