RAF Flight Lieutenants

John Peters and John Nichol

with William Pearson

TORNADO DOWN

This book is dedicated to the members of XV Squadron, all of whom served with such distinction during Operation Desert Storm

January 17, 1991. UK: BRITAIN SAID TO LOSE ONE FIGHTER-BOMBER

LONDON, Jan 17, Reuter: A British Tornado fighter-bomber has been lost during raids on Iraqi targets, according to military sources in the Gulf quoted by the Press Association national news agency.

The agency said it was understood to be the first loss among seventy-five British warplanes in the region in Thursday’s fighting.

The precise looation of the incident and the fate of the two crew were unknown. The aircraft was engaged in a second wave of daylight raids after the initial attacks under cover of darkness.

REUTER NEWS SERVICE

Writing a book, especially one of this nature, is not a simple project. We are indebted to a number of people for their help, encouragement and support.

First and foremost we must thank Will Pearson who actually put our words onto paper in a manner that we could never have achieved; without his time and dedication there would be no Tornado Down .

A number of other people guided us through the literary minefield and we are very grateful to them. Our agent Mark Lucas at Peters Fraser & Dunlop deserves special mention for being our mentor over the last year.

We are forever in the debt of the teams of medics and psychiatrists, led by Wing Commander Gordon Turnbull, who were there to meet us when the Red Cross flew us out of Baghdad. They ensured our return to normality was as smooth as could be expected. Others who showed great understanding and support were our Station Commander, Group Captain Neil Buckland, and the Squadron Commander who led us to war and was there on our return, Wing Commander John Broadbent DSO.

Wing Commander Andy White took over XV Squadron a few months before it was disbanded in 1991. His support, and that of the RAF Public Relations Department, was especially appreciated at what was a very difficult time for the whole squadron.

A vote of thanks also goes to our solicitors, Richard Taylor and Charles Artley from Simkins, for their legal expertise and advice during some very trying times.

Finally, we must thank the many thousands of well-wishers who sent messages of hope and support to our families during our imprisonment and to ourselves on our release; we are indebted to you all for your concern.

Many of our experiences have been shared, but we would also like to add our personal thanks.

John Peters: I would like to thank all my friends at Laarbruch who supported Helen and the children during my captivity; in particular, I would like to thank the two Maggies, Mrs Buckland and Mrs Broad-bent.

Finally, but most importantly, I thank my mother and father, brother and sister, and Helen’s family simply for being there. They didn’t ask for the worry and stress, the speculative horror stories or the constant media barrage. On my return they asked for nothing more from me.

John Nichol: My family had an extremely trying seven weeks whilst I was missing in action. In some ways, thanks to the intense media harassment and mindless speculation, they were subject to worse treatment than myself. There were a number of individuals and organisations who supported and protected them over those distressing weeks.

Inspector Tom Hilton and the Northumbria Police had their work cut out shielding my family from the forces of the media. They did this with the help and co-operation of the personnel from RAF Boulmer who also ensured that help and advice was never more than a telephone call away. Flight Lieutenant Ian McNeill was particularly supportive in his role as their liaison officer. The staff at British Telecom were invaluable in ensuring that unwanted telephone calls never bothered my family. The Rt Hon. Neville Trotter MP was a constant source of encouragement, as was Father Dominic McGivern and the parishioners of St Joseph’s Church. Finally, the Post Office staff ensured that the many thousands of well-wishers’ letters arrived despite the fact that few were correctly addressed!

On a personal note, I must thank Steve Barnfield for helping to take care of my affairs during my enforced absence. Thanks also go to Bernie Middleton, John Wain and Yvonne Andreou for allowing me to use their flat as an office and also for providing a memorable homecoming party along with the rest of the Avenue Road Mafia!

Finally, and most importantly, I send my love and gratitude to my family for being there and supporting me on my return from Iraq; to Paul, Angela and Christopher, to Brendan and Margaret, to Teresa, Stephen, Kate and Clare, to my parents: thank you.

William Pearson: My thanks go to Arianne Burnette of Michael Joseph for her sound editorial advice; Flight Lieutenant Simon Pearson, RAF, for his technical expertise and encyclopaedic knowledge of modern combat operations; and special thanks also to Gaynor Williams.

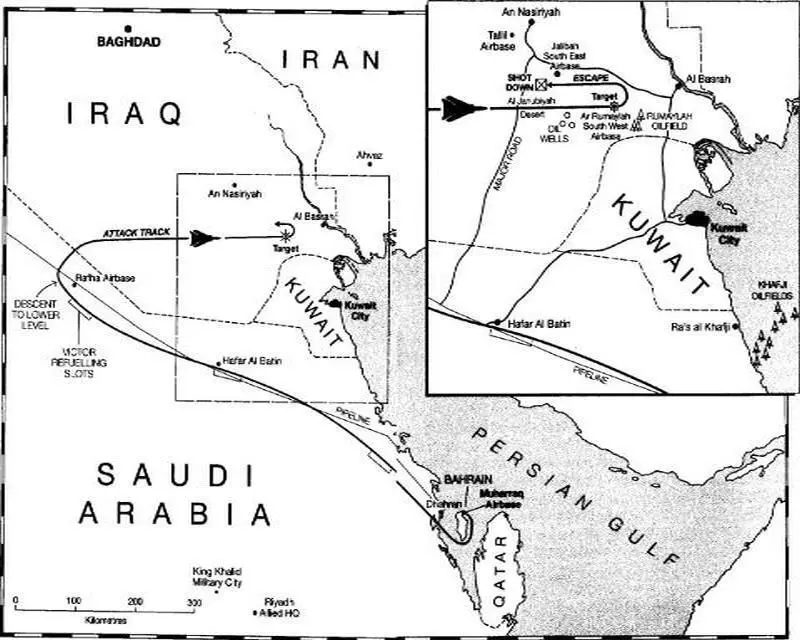

John Peters: The Tornado was doing 540 knots fifty feet above the desert when the missile hit. A handheld SAM-16, its infra-red warhead locked onto the furnace heat of the aircraft’s engines. Some lone Iraqi’s lucky day. Travelling at twice the speed of sound, the SAM streaked into the bomber’s tailpipe, piercing the heart of its right turbine. Five kilograms of titanium-laced high-explosive vaporised on impact, smashing the thirty-ton aircraft sideways. It shuddered, a bright flame spurting from its skin; fifteen million pounds-worth of high technology crippled in a moment by the modern equivalent of the catapult. The computerised fly-by-wire system went down, transforming the aircraft instantly from thoroughbred to cart-horse.

We had just completed our attack run on the huge Ar Rumaylah airfield complex, in southwestern Iraq; I was pulling the Tornado through a hard 4g turn, with sixty degrees of bank, to get onto the escape heading. The aircraft was standing on one wing, at the limits of controllable flight. The fly-by-wire loss sent it rumbling, the stick falling dead in my hands – a terrifying feeling for a pilot. I was pushing the controls frantically, the Tornado falling out of the sky, the ground ballooning up sickeningly in my windshield. The huge juddering force of the blast had knocked the wind out of me. Gasping, hanging off the seat straps, I yelled: ‘What the hell was that?’

‘We’ve been hit! We’ve been hit!’ John Nichol, my navigator, shouted from the back seat. Urgently, he transmitted to the formation leader: ‘We’ve been hit! We’re on fire! Stand by.’

‘Prepare to eject, prepare to eject!’ I yelled. ‘I can’t hold it!’

‘Don’t you bloody well eject! Get hold of it!’ he shouted. It steadied me.

Fast jet aircrew do not survive collision with the ground at 540 knots. There is a one hundred per cent certainty of death. The Tornado’s wings were still swept back at forty-five degrees for the high-speed dash home. I threw the lever forward, desperate to prevent the looming crash. Incredibly, it worked: despite the fire and the enormous loss of power, the aircraft responded, lurching back under something like control as the wing surface, swept forward now at twenty-five degrees, bit harder at the airflow. Still wallowing horribly, the aircraft began to climb, but with agonising slowness. I nursed the stick back to gain precious altitude. Having avoided immediate collision with the ground, I had an awful awareness that the best thing would be to climb to a safe height. But we were still in a high threat area, not far from the target. We had to remain low until we were clear of the road, crawling with Iraqi troops, that we had crossed on the way in, before zooming to height for the return home.

Читать дальше