Presidential palace, Kabul, 17 November

‘Why all this delay? Why have we had so many meetings on this?’ said the president at the War Cabinet. He was getting impatient and unpredictable.

Karzai had been speaking constantly to Mullah Salaam, as well as to the former Helmand governor and nemesis of the British, Sher Muhammad Akhundzada. He had spoken too with the Musa Qala elder who had negotiated the truce agreement the previous year that secured the British pull-out. The latter was an uncle of the main Taliban leader in Musa Qala, Mullah Torjan. But all these leaders of the Alizai tribe were right behind an action to seize the town back for the Afghan government. This was a ‘historic opportunity’, said the president. For the first time that anyone could remember, certainly since the war with Russia, the subtribes of the Alizai were coming together.

The NATO commander was listening. It was time, he thought, to strike a clear deal of his own. Until now, Karzai had been talking endlessly about action but had been endlessly vague about what exactly he wanted.

‘So, Mr President, you want me to do this thing?’

Karzai nodded.

‘I will be happy to set the right conditions – but I want Afghans to go into the district centre.’

General McNeill said the plan was for NATO forces to surround the town, to bear down with pressure on all sides. That would pave the way for an Afghan force to push through the town itself.

‘Yes. We want it like that,’ said Karzai.

But McNeill said he wanted Karzai’s agreement on two more things. Firstly, Afghans had to hold the place afterwards. He did not want another beleaguered British force left to defend itself. Secondly, he wanted ‘better governance’ down in Helmand. It was a strong and clear hint that Karzai should sack Governor Wafa.

‘Go ahead, then,’ said Karzai. But no civilians should be killed, he said.

‘It won’t be my aim, Mr President, but I can’t make that guarantee. We can do this thing, but stuff will get broken,’ said the general. ‘And we need some time here, you know.’ It would take until December to assemble his forces.

Karzai looked unhappy at that.

Bismullah Khan, the Afghan army chief of staff, intervened. Speaking in Dari, he said Afghan forces were not only ready to go up and reinforce Salaam but could quite easily take Musa Qala on their own.

That just angered McNeill. Five times since he had taken command in Afghanistan, Karzai had rejected the general’s suggestion of an operation to recapture the town. Now, after finally giving the green light, the Afghans wanted it done yesterday. There was also delusional thinking going on here, thought McNeill. A ‘tribal alliance’ might make the people welcome the Taliban’s removal. That was crucial to the future. But it was not going to drive a bunch of jihadi fighters and narco barons out of town. Nor would the toothless Mullah Salaam help. And nor could the Afghan army do it on their own. They were becoming better trained and more effective. But, if they attacked alone, they would be slaughtered.

None of this was said to Karzai, however. In a gathering like this, no one was going to shatter his pride. In fact, as one senior westerner present at such meetings wondered aloud to me, ‘Was the president in his palace ever getting the raw truth?’

McNeill concealed his feelings. Backed by the US ambassador, the general said diplomatically that it would simply be better to wait for all forces to be in place. ‘Otherwise the Taliban will simply escape.’

Karzai was still not satisfied. What exactly was the plan to go and rescue Mullah Salaam if his compound was assaulted by the Taliban? It would be the ‘worst possible outcome’ to pull out Salaam in ignominious defeat, with his tail between his legs.

The Afghan defence minister suggested a separate plan to protect Salaam. That calmed Karzai.

For all the president’s frayed nerves, an agreement was finally in place. Musa Qala would be taken by force. NATO troops would surround the town, but the decisive part of the operation, the seizure of the town itself, was to be done, it was agreed, by the Afghan army.

The meeting that approved an ‘Afghan-led’ military action had taken place with the British ambassador still away on leave. Cowper-Coles, who had been the voice of caution, was to get a shock when he returned.

McNeill swung rapidly into action. That night he summoned Brigadier Mackay up to Kabul to brief him the following day on how this operation could work. Mackay informed London: ‘COMISAF has directed that the conditions have been met to launch decisive operations against Musa Qala.’

The desert west of Musa Qala

They knew they were being watched everywhere. The Taliban had their ‘dickers’ – as the British called the spotters – on motorbikes or trucks or dug in somewhere. They were shadowing the British forces out in the desert and calling down mortars and rockets to attack their positions.

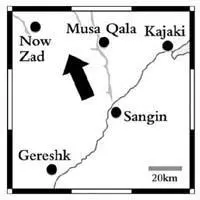

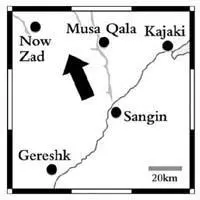

To the east and west of Musa Qala, the two mobile operating groups, the eastern commanded by Major Chris Bell and his Warrior company and the western by Major Tony Phillips’ Brigade Reconnaissance Force, were now in daily battle with the Taliban as they probed the town’s outer defences. Raids by US special force Green Berets were also intensifying – targeting Taliban strongholds in villages to the south of the town.

Out to the west, Phillips recalled ‘we were the only show in town’ for the Taliban. All day long, listening to the Taliban’s radio network, his men heard their enemy preparing to attack. ‘We could hear them broadcasting a running commentary of what we were doing. And we would later find out why: the enemy had observation points in the high ground.’

As they manoeuvred in the desert, the BRF’s contact with local Afghans was sporadic, and those they met were cautious. One bedouin shepherd, wandering alone in a pair of trainers, said it all when he spoke to Captain Duncan Campbell, one of the officers, and threw up his arms in despair. ‘You are always coming here to ask about the Taliban. The Taliban come and ask about the British. Me, I’m still looking for my sheep!

Getting supplied was everything on this desert patrol. Most of it came by parachute – palettes pushed out of a Hercules plane on to a drop zone they marked at night. Sometimes it was a Chinook chopper. That was the best because it brought the mail (too risky to drop by air) and maybe some cigarettes. They would feast for a while on parcels from their families. And then it was back to the boil-in-the-bag field rations. For a while, they ate special halal Muslim food. They had ordered some for the interpreters but then got three months’ supply for everyone. And no British rations.

Life developed a pattern out here. In the day they approached the Taliban-held villages, always targeting a new place and always by a new route. And at night they retreated back to their harbour, set up camp and cooked their rations. For the moment, even as they fought the Taliban on a daily basis, the BRF seemed to be blessed. They struck no mines and they took no injuries. They remembered how, after the suicide strike, the locals in Gereshk called them the ‘warriors protected by God’.

Their life had a certain romance. They looked like the SAS with their long beards and dusty smocks and shemagh headdresses. But most just found it plain hard, and sometimes boring.

‘I enjoyed it, to be honest with you,’ recalled Simon Annan, a thirty-year-old sniper. ‘But you have the same conversations with everybody. It’s just Groundhog Day. It’s almost like you want something to happen because it gives you something else to talk about. There were periods we sat for two or three days doing nothing, prepping for something. You’ve just got to try and motivate yourself.

Читать дальше