OPERATION SNAKEBITE

The build-up around Musa Qala

2 November to 3 December 2007

Siege around the rebel citadel

After the truce brokered by town elders, British forces had withdrawn from Musa Qala in October 2006. The town became a Taliban stronghold. Under pressure from President Hamid Karzai, Operation Snakebite is launched to protect a Taliban commander, Mullah Salaam, promising to switch sides, and launch a revolt of the tribes. The mission escalates until British and US forces surround the town from the desert.

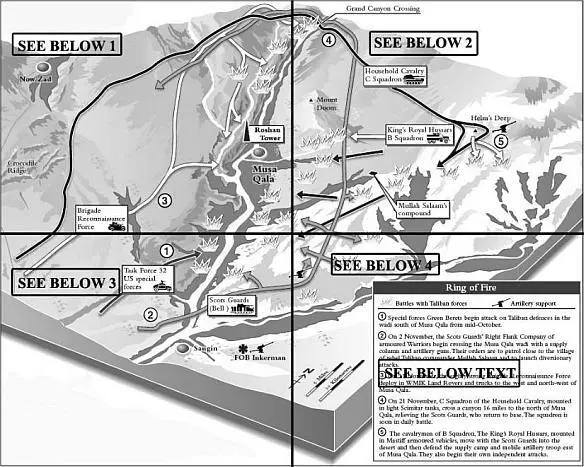

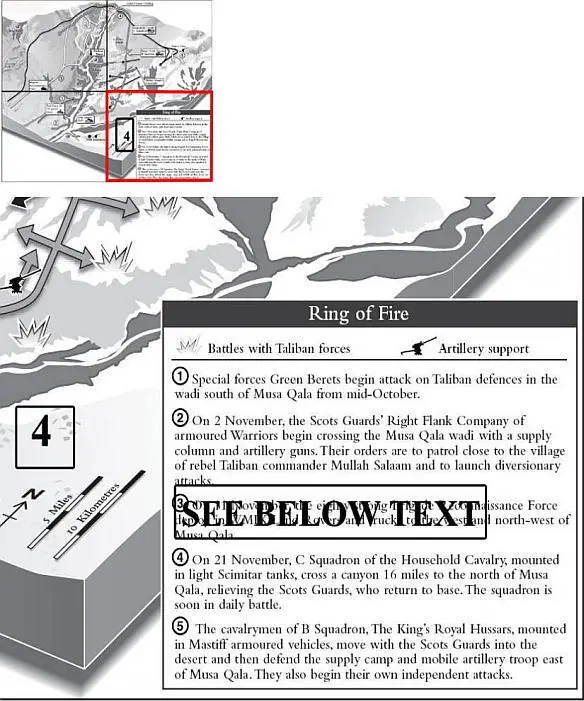

Ring of Fire

Battles with Taliban forces

Artillery support

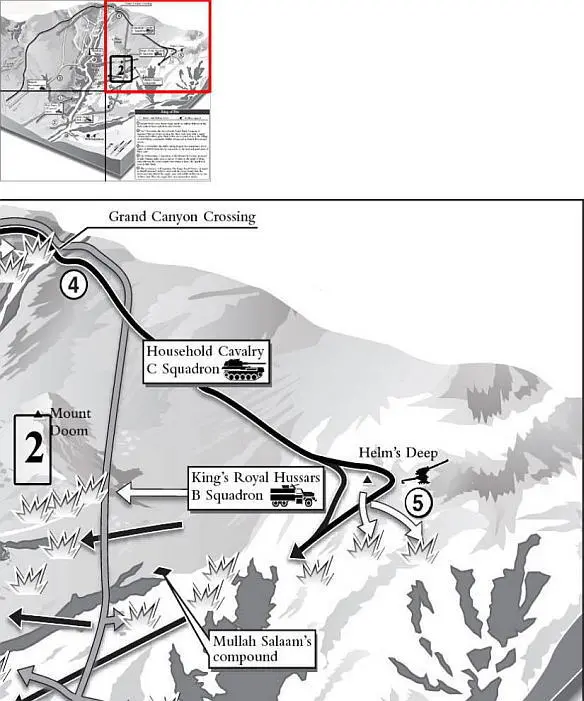

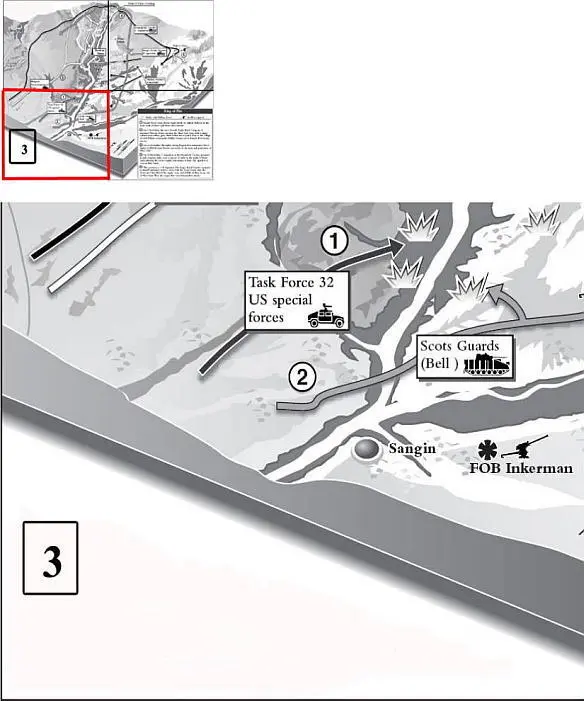

(1) Special forces Green Berets begin attack on Taliban defences in the wadi south of Musa Qala from mid-October.

(2) On 2 November, the Scots Guards’ Right Flank Company of armoured Warriors begin crossing the Musa Qala wadi with a supply column and artillery guns. Their orders are to patrol close to the village of rebel Taliban commander Mullah Salaam and to launch diversionary attacks.

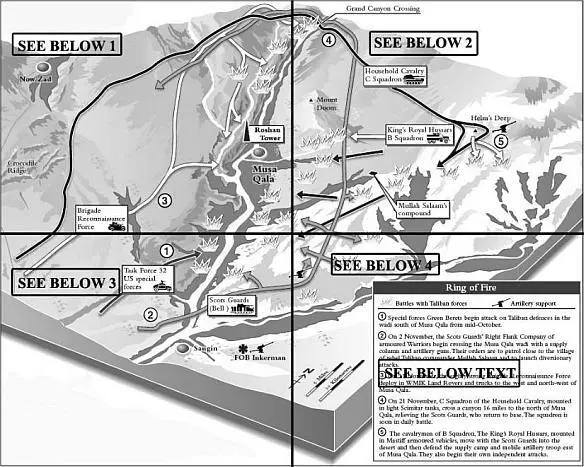

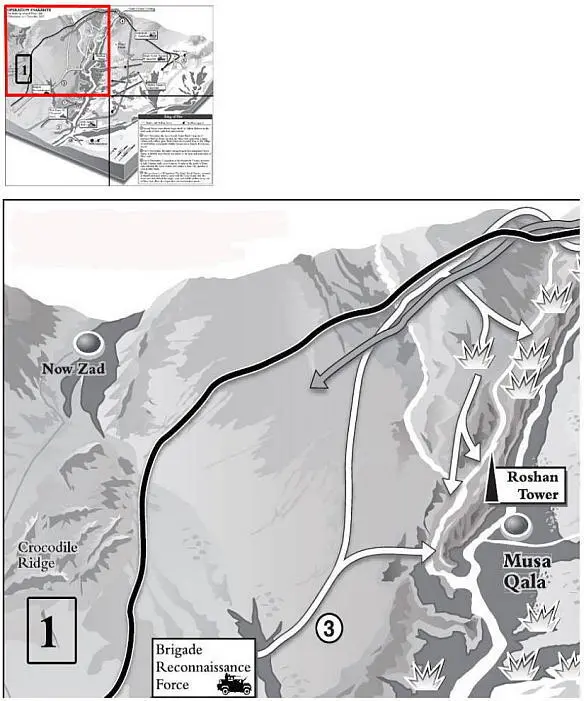

(3) On 11 November, the eighty strong Brigade Reconnaissance Force deploy in WMIK Land Rovers and trucks to the west and north-west of Musa Qala.

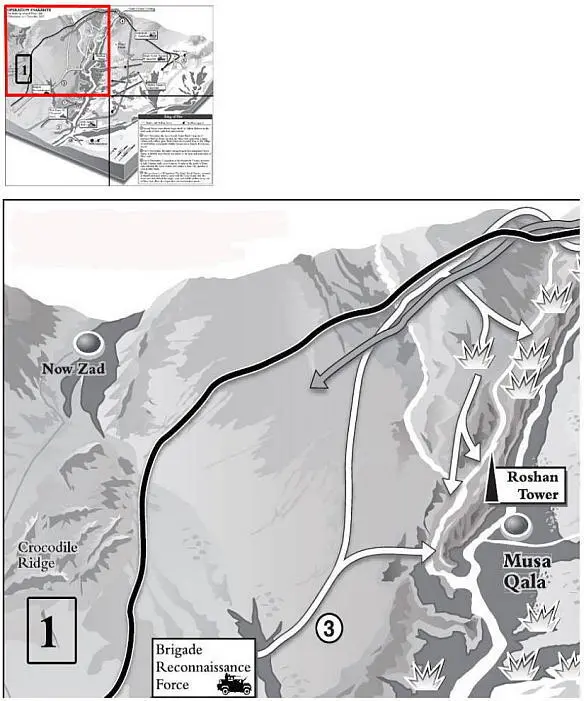

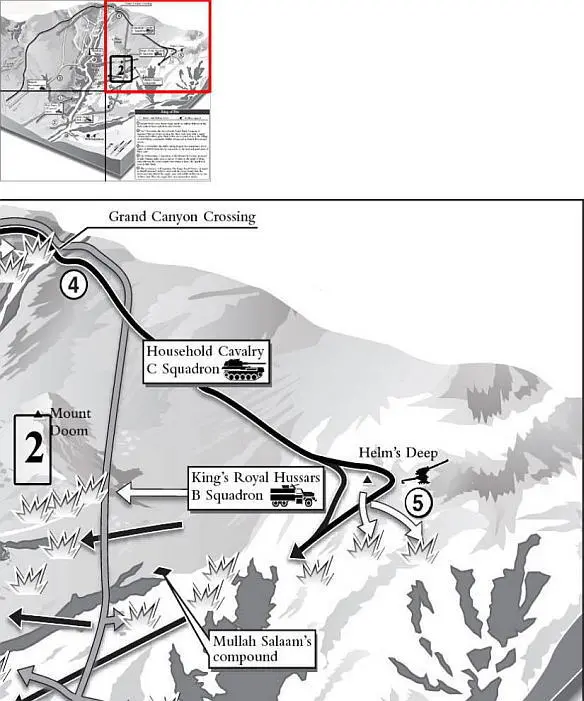

(4) On 21 November, C Squadron of the Household Cavalry, mounted in light Scimitar tanks, cross a canyon 16 miles to the north of Musa Qala, relieving the Scots Guards, who return to base. The squadron is soon in daily battle.

(5) The cavalrymen of B Squadron, The King’s Royal Hussars, mounted in Mastiff armoured vehicles, move with the Scots Guards into the desert and then defend the supply camp and mobile artillery troop east of Musa Qala. They also begin their own independent attacks.

‘The captives of our bow and spear Are cheap – alas! As we are dear’

Rudyard Kipling, ‘Arithmetic on the Frontier’

Forward Operating Base Delhi, Garmsir district centre, 18 November

It was early in the morning when a truck pulled up to the gates of the base. On sentry duty, the Gurkhas of B Company, 1 Royal Gurkha Rifles, could see the bodies of several wounded Afghans slumped in the back. The injured were angry. They claimed that foreign and Afghan soldiers had raided their village by helicopter. At least eighteen people, including children, were dead. Their homes – which the Afghans later identified as the village of Toube – were about twenty minutes’ drive to the south, on the Taliban side of the front line. The Gurkhas were surprised. They knew of no operations which had been underway that night. Either the incident was invented or this was the result of something secret, most likely the work of special forces.

There were two hospitals in the area of Garmsir. One was the medical centre at the Delhi base. The other was run by the Taliban. Why had they chosen the British base? the Gurkhas wondered. Some of the injured were men of fighting age. They could be Taliban. Their blast and gunshot injuries suggested a fire fight. But, if they were Taliban, why had they come here?

The doctor on duty was perplexed by some of their injuries. They needed more specialist care. ‘It’s pretty inconclusive either way,’ he told the Gurkhas. He decided to send the injured onwards to the civilian hospital in Lashkar Gah.

No public announcement was made of the incident that day. No statement was released to the press. But the incident would not be forgotten.

More than three weeks later, a report appeared on the Internet from an international news agency, the Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR). The agency, which works across conflict zones, had received British funding to train journalists in Helmand in the basics of news reporting. Now these same local journalists had their scoop. The headline read: ‘Foreign Troops Accused in Helmand Raid Massacre’. The IWPR reported the story of a young baker called Abdul Manaan, who was still lying in Lashkar Gah’s emergency hospital with his throat bandaged. He claimed to have survived despite his throat being cut by a group of soldiers – Afghan and foreign – that arrived by helicopter on 18 November. The IWPR reported:

‘It was about two in the morning when we heard the aircraft, and I woke up,’ said Abdul Manaan. ‘My two younger brothers came to me to ask what was going on, but I told them, “Nothing, just go back to sleep.”

‘Then I heard a noise on the roof, and I looked out and there were armed men up there. They climbed down and came into my brothers’ room, and asked them if they were Taliban. One of my brothers said “No, we are shopkeepers, come and search the house. We have nothing, no guns or anything.” The soldiers shot him on the spot. My other brother they brought to me, and tied his hands. Then they slit his throat. I could hear him gurgling. He was still making a noise when they got to me.

‘They made me stand up against the wall and tied my hands. They put the knife to my neck and cut me three times. Then they threw an old tarpaulin over me and left.

‘But I wasn’t dead.’ [16] Matiullah Minapal and Aziz Ahmad Tassal, ‘Foreign Troops Accused in Helmand Raid Massacre’, Afghan Recovery Report No. 277, 11 December 2007, Institute for War and Peace Reporting, www.iwpr.net/?p=arr&s=f&o=341341&apcstate=henparr .

As Abdul Manaan lay under the tarpaulin, holding his hand to his neck wound, he heard the soldiers moving around the house and children screaming. When the soldiers left after about half an hour, he said, ‘I got up and went to my brother. He was cold.’ He found the women and children alive in another room, together with some who had come from other houses. ‘Everyone was screaming and crying,’ he said.

In the morning, Abdul Manaan was taken to hospital in Lashkar Gah. ‘I survived, but my brothers are dead,’ he said. ‘What shall I do now?’

For months now the IWPR had documented frequent cases of civilians dying in NATO bombing raids. Often the coalition claimed that Taliban had been fighting from or hiding in the compounds of ordinary civilians. Their deaths were accidental. But this raid appeared different and far more brutal. The report continued:

Abdul Manaan’s story is echoed by dozens of villagers from Toube whom IWPR interviewed as they underwent treatment in Lashkar Gah or accompanied injured relatives there. All spoke consistently of soldiers breaking down doors, shooting children and cutting throats. They agreed that the raid began at two in the morning with the sound of helicopters bringing in dozens of armed men, both Afghan and foreign.

Who was really responsible for the raid? And what was the truth of the events that night?

After the injured had left, a phone call came in from a secret unit, asking for the identity of the injured they had treated. Major Mark Milford, the B Company commander, was less than impressed. Why had they not bothered to inform him of the raid? Technically, the target was outside the area he controlled. But only just. And, as night follows day, it was his company of Gurkhas that would be left picking up the pieces – and dealing with any local anger that followed. For the Afghans, the forces involved were simply ‘foreign troops’ backed by local soldiers. American or British, special forces or conventional troops. They could not tell them apart.

Читать дальше

Battles with Taliban forces

Battles with Taliban forces  Artillery support

Artillery support