The desert west of Musa Qala, 11 November (Remembrance Day)

Major Tony Phillips crawled into his plastic bivvy bag and zipped the top shut over his head. He switched on his red head torch. Then he opened his personal diary to scrawl a brief note. It had been a long day.

A few minutes before, as the last golden light faded beneath the black shadows of the distant mountains, his elite Brigade Reconnaissance Force had been on ‘stand to’. That was the centuries-old warrior tradition of standing ready for action at the close and break of day, ready to repel an attack at the classic moments of danger. Then all lights had been put out and all his men had fallen silent. Soon, the only noise was the snores of men and the howl of the wolves that crept around in the darkness. The sentries would see them moving through their night-vision goggles.

As he gathered his thoughts, Phillips could not know then what lay ahead, that this night would be the beginning of what would become an epic three-month adventure and one of the longest British desert patrols in memory. It would be tinged with tragedy. When they were all assembled, the BRF patrol of eighty men that had left the green zone behind would finally come out of the desert with twelve men down – ten injured and two who would be killed in action.

For now, though, Phillips was still filled with the thrill of his mission – the danger of the enemy that lay all around and the large area he was being asked to cover, and the responsibility that lay on his shoulders. His mission was reconnaissance for Brigadier Andrew Mackay, who used to describe the BRF as ‘my eyes and my ears’. But where the BRF went within that mission – and how they did it – was Phillips’ choice, and his alone.

‘There are no two ways about it,’ he wrote quickly, ‘this is the brigade commander’s baby! It’s his idea and we are working directly to Brigade. I have an area of nearly 300 square kilometres in which to do what I want. It’s all very exciting. We are in the middle of the desert so should be safe but as Musa Qala has hundreds of Taliban and is their stronghold they could try anything.’

A native of Lancashire, thirty-eight-year-old Phillips had a reputation as something of a rough diamond. By his own description he was ‘not exactly your clean-cut nose-clean type of officer’ and not infrequently he got into trouble for speaking his mind. Someone once described him as a ‘break glass in time of war’ type of leader, valued most of all for his physical tenacity and personal courage. Joining the army after a geography degree at Manchester University, he had seen action in Northern Ireland as a troop commander and dealt with the aftermath of an IRA bomb that killed one of his soldiers.

A week ago, Phillips and his men were still in the lush green zone of the Helmand River valley. His force had been manning a patrol base just north of Gereshk. It had been classic counter-insurgency work of the sort that Mackay favoured – getting out to talk to the locals, helping them with some basic medical care and establishing a stable government presence in a village, Zumberlay, that a year earlier had been Taliban heartland and where my colleague at the Sunday Times , Christina Lamb, had been with the Parachute Regiment as they were pinned down by gunfire.

The BRF had already had their baptism of fire. Ironically, the first fire fight had been not with the Taliban but with the Afghan National Police. They had been driving in the night out of Camp Bastion when they came under a volley of machine-gun fire. Only later did they find out who their adversaries were.

Then they had been attacked by a suicide bomber just on the outskirts of Gereshk town. A white Toyota Corolla ( it always seemed to be a Corolla ) came haring towards them. Only quick reactions saved his men. Four of his soldiers had opened fire on the driver, and the car exploded between two vehicles. There were minor injuries, but the main effect was a wake-up call. It made them realize the training phase was over.

The incident that most affected the men down in Zumberlay had been when they tried to help a young Afghan boy. He had burned himself with hot milk that poured all over his skin, and the wounds had been left to fester. The medics had spotted it was a highly serious injury. But appeals to send him to a coalition hospital had been rejected. So the soldiers intervened themselves and collected 300 dollars for him. The boy was driven over to Gereshk and handed over to the Afghan police to take him for treatment. But the next morning he came back wrapped in a carpet. He had died in the night.

Then the orders came through from Brigade to move into the desert. Really the only no-go zone for them was the town of Musa Qala itself. Everywhere else they were to probe relentlessly: testing the Taliban reactions, working out their defensive positions, assessing their strength and figuring out routes for any future NATO advance.

Everyone slept at night by their vehicle on the rocky desert floor, contending not only with fearsome camel spiders, up to six inches long, but also with snakes that might come seeking warmth. Recalled Phillips: ‘Nobody was permitted to move outside the “box”, so cooking, sleeping, washing and pooing all occurred within a few yards of the vehicle, and its crew. There was no room for shyness.’

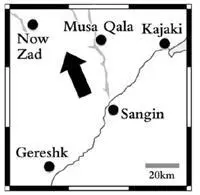

This was Taliban country. To his north-west was the town of Now Zad, surrounded on all sides by the enemy. To his east was the Musa Qala wadi, 30 miles of green zone running north to south and entirely in the enemy’s hands and the Taliban stronghold of Musa Qala town slap bang in the middle. And throughout the desert in between were small pockets of settlement, each one a potential place from which to be ambushed.

There were also objective dangers. The intelligence maps he was given showed clouds of red – marks that indicated the presence of thousands of mines left behind in the desert by Soviet troops.

They got attacked almost as soon as they arrived. In the desert it was mortars, thankfully missing them by hundreds of yards, but always setting nerves on edge. As they approached the Musa Qala wadi and the villages around, it was gunfire and RPGs that awaited them.

14. War, Tea and Sugared Almonds

The mission of the European Union, Kabul

Michael Semple was at his desk and glancing at his diary. He was halfway through a busy day – nine meetings, beginning with breakfast with a close relative of the elusive Taliban supreme leader, Mullah Omar, and with an office call to a senior official in Afghan intelligence, the NDS, planned for 15.30. His mobile phone rang. It was Naquib, his Afghan partner, calling from a guesthouse in the city suburbs. He spoke in code, something like: ‘The Eagle has landed!

In all his months of meeting with the Taliban, people always wondered how exactly Semple did it. Was he mad or foolish? How could he meet these people safely? Did he have to be disguised or protected? But Semple had a big secret: rather than disappearing off to meet the Taliban, the Taliban came to him, frequently in Kabul. It said something about the nature of this war. The British and Americans wore uniforms, looked foreign and drove about in armoured cars. Moving just 10 miles took hours of planning. But their enemy wore no uniform. They had the freedom of the roads. A Taliban leader could wake up in a Helmand trench one morning, put down his AK-47, get a lift to Kandahar and a bus to Kabul and be up there in a single day.

Читать дальше