By the time the patrol walked into Inkerman at 18.20, the sun had set more than an hour before and it was almost pitch dark. They heard a round of applause from those back at camp.

For Ogden and the other medics there was still another three hours of work – patching up Captain Britton and pulling out the bits of shrapnel from the others. They discovered that many of the marines had caught bits without realizing. The evening ended with a naked parade as Ogden and the others went down the line, inspecting everyone to check they were unscarred.

Brigade headquarters, evening of 9 November

The chief of staff, Major Mark Gidlow-Jackson, picked up the ringing phone on his desk. It was Major General Jonathan ‘Jacko’ Page, Brigadier Mackay’s immediate superior in the NATO command, and he rang with orders from General McNeill.

‘I’ve just spoken to COMISAF,’ said the general, referring to McNeill’s title. ‘At this stage there is more political work to be done on Musa Qala.’ There was a question mark on Karzai’s attitude. But it was now clear an operation to retake the town was on the cards. ‘The government will take a kinetic solution if it’s required,’ he said, using the military’s term for a fight.

Already NATO was earmarking forces for a possible assault. The Afghan army’s most elite unit, the Commando kandak , trained and mentored by US special forces, was being put on notice to move. So was McNeill’s own reserve force, the Theatre Task Force, Task Force 1 Fury, led by Lieutenant Colonel Brian Mennes. They would not be available for three weeks, but certainly no later than 10 December.

It was time for some serious planning. ‘I want thoughts on the whole Musa Qala piece to me by next Wednesday,’ concluded the general.

That night was what Brigadier Mackay would recall as the loneliest moment in his command. As he sat in the office in Lashkar Gah and paced around in the darkness of the base, he had to consider his next move. His forces were now clearly stretched. The pressure on Musa Qala applied by the presence of Chris Bell’s Warrior company and its daily skirmishes was having an effect. But the Taliban’s own counter-attack was getting stronger by the day. Now there were strong hints from President Karzai not only that Mullah Salaam should be protected but that an attack should be prepared on Musa Qala itself.

But was it right to risk all on the Musa Qala prize? His hope when he arrived had been to get some development going in Helmand, to move beyond the fighting. The priority had been war-ravaged Sangin, which had been held for the last six months but had seen almost no progress. If the cost of supporting Mullah Salaam and hitting the Taliban in Musa Qala was that Sangin simply dissolved back into violence, the whole venture could be seriously counter-productive. Not to mention the cost in blood for his own soldiers.

Mackay flew to Camp Bastion the next morning to visit the injured from the battle at Inkerman and elsewhere. Lying in bed was Corporal Greening, a man he had met on a visit to Inkerman only five days back. Greening had asked, ‘When are we going to get stuck into the enemy?’ They had a joke about it now. ‘Didn’t I say to be careful what you wish for?’ he said. Greening said that when he was shot he had thought at first he was winded. ‘Then I noticed the blood,’ he said.

As he sat in a helicopter heading back to his headquarters, Mackay made his decision. Rather than draw back his forces from the battle, he would do the reverse and ratchet up the psychological pressure on Musa Qala one more notch. ‘I had a sense we were actually succeeding,’ he recalled.

While the Warriors and their support group were probing the eastern flanks of Musa Qala around Salaam’s compound, for now the desert to the west of Musa Qala was unexplored. It was time, decided Mackay, to deploy his own reserve asset – the Brigade Reconnaissance Force (BRF) led by Major Tony Phillips. It would mean taking the BRF out of the green zone – where the Taliban were now gathering strength – and opening a new front: deeper into enemy territory.

As he laid out his orders to staff, there was a sense of the stakes being raised in a game of poker. One adviser told him later his thoughts then were: ‘If this goes wrong, Mackay is absolutely fucked. That is a big big call to make.’

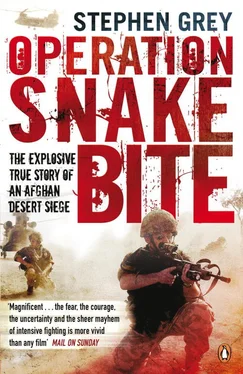

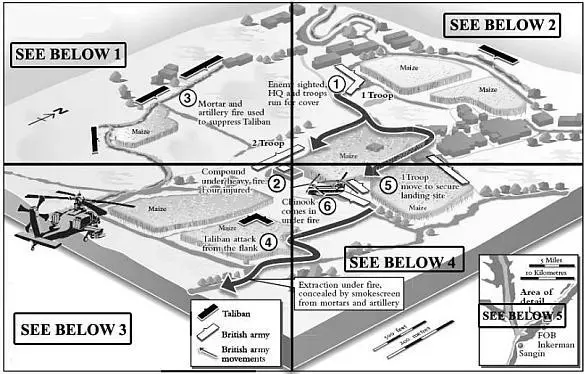

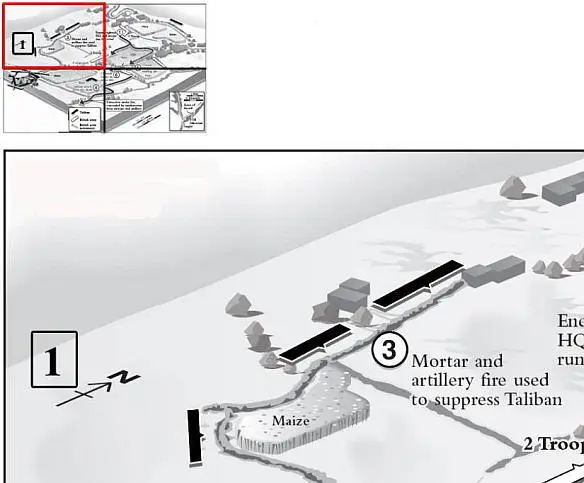

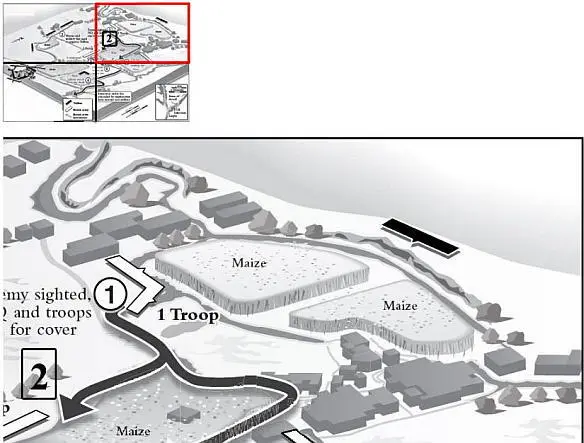

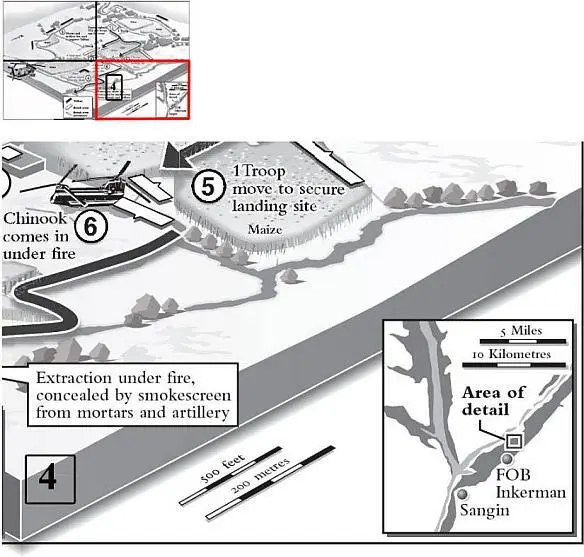

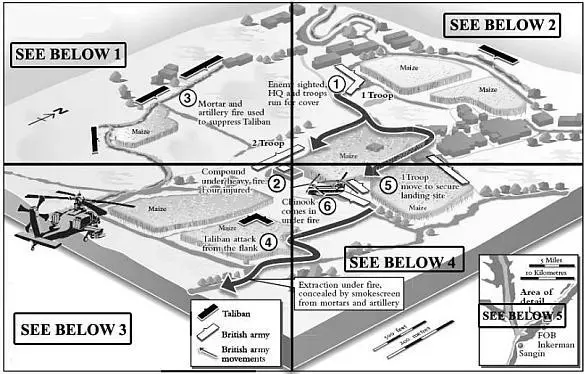

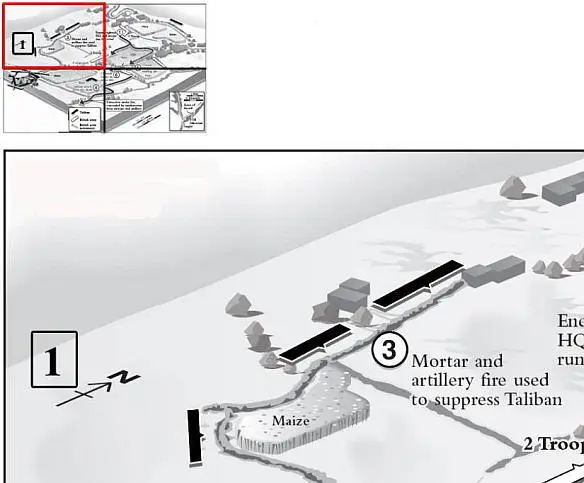

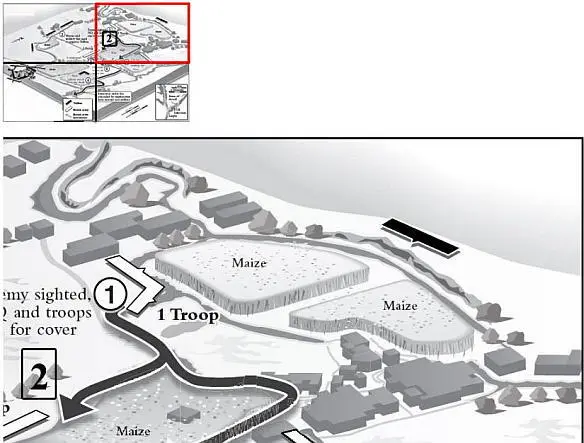

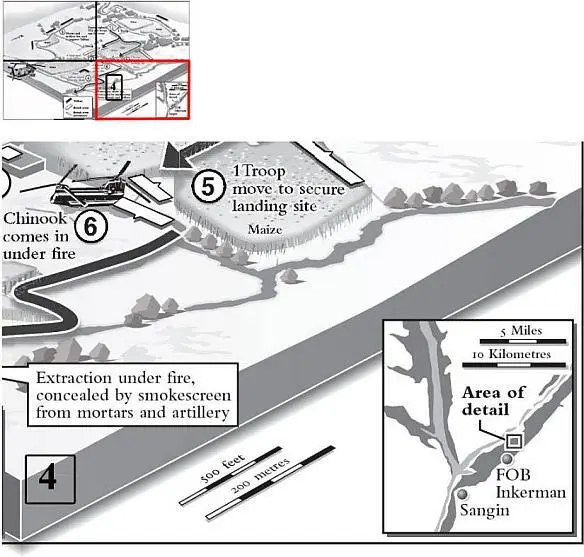

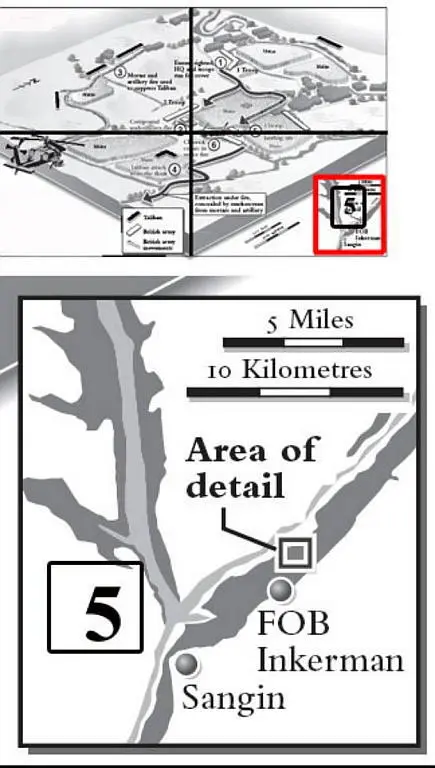

BATTLE OF 9/11

Outside FOB Inkerman

9 November 2007

Alpha Company of 40 Commando Royal Marines return to FOB Inkerman after a six-hour patrol. All day they heard intelligence of an imminent ambush. It came at 16.06. Within three minutes, two marines are seriously wounded, and two more hurt. The Taliban begin to surround them.

‘Playing chess by telegraph may succeed, but making war and planning a campaign on the Helmand from the cool shades… is an experiment which will not, I hope, be repeated.’

British officer (anonymous) after the defeat of Maiwand, 1880

[15] Major Waller Ashe, ed., Personal Records of the Kandahar Campaign: by Officers Engaged Therein , Elibron Classics facsimile replica of the 1881 edition published by David Bogue (BookSurge Publishing, 2005), p. 98.

Operation Snakebite

At 03.30 on 11 November, the first elements of the Brigade Reconnaissance Force (BRF) leave a patrol base in the green zone near the village of Zumberlay under the command of Major Tony Phillips. They take the road through Gereshk and then turn right into the desert.

The following day, the second half of the force, commanded by Captain James Ashworth, leaves at 04.30 to rendezvous with them to the west of Musa Qala.

The force is mounted in eighteen WMIK Land Rovers and six Pinzgauer trucks, and the total strength of eighty men consists of two fighting troops totalling forty-eight men, a fire support group armed with two 81 mm mortars, snipers and Javelin missiles, a unit that can deploy a small UAV ‘Desert Hawk’ drone and a headquarters element.

They are travelling light. Everything they need to survive is carried in their vehicles. While Chris Bell’s Warrior company, the Mobile Operation Group East, has its own special supply camp – with truckloads of fuel, ammunition and supplies, and a troop of three field guns to support them – the BRF are on their own.

Their destination is to be called Operations Box Inferno, and Major Phillips’ orders state: ‘Carry out reconnaissance north and west of Musa Qala, find and disrupt the enemy, and influence the civilian population.’

Their camp at night is known as a ‘harbour’, a place of refuge in a sea of sand and rock. It is to be strictly arranged in the shape of a box, with the fighting troops guarding the corners and the headquarters and fire support team, including mortars ready to fire, arranged in the middle .

Читать дальше