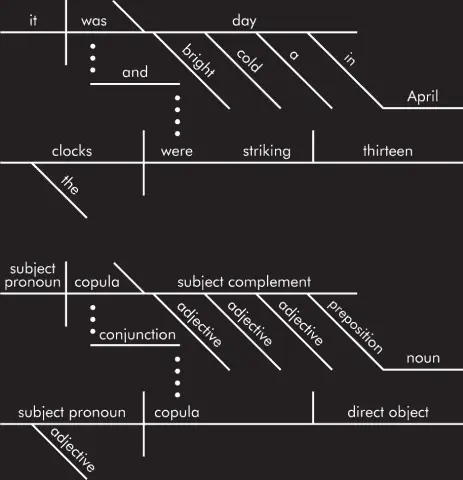

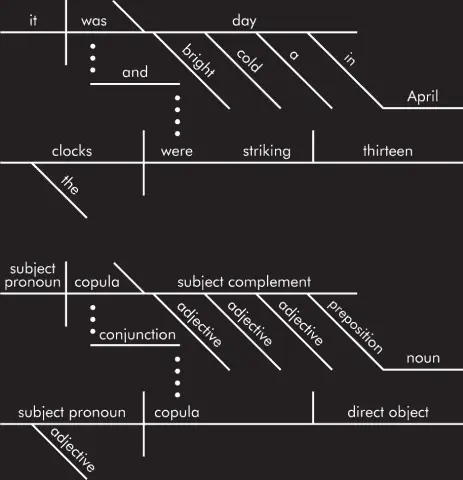

DN:You talk about the usefulness of diagramming sentences, that by diagramming them you discover that sentences have skeletons.

UKL:I wasn’t taught that in school—that was the previous generation. My mother and my great-aunt could diagram a sentence, and they showed me how. I enjoyed it; for anyone who has that kind of mind, it’s illuminating. It’s kind of like drawing the skeleton of a horse. You go: “Oh, that’s how they hang together!”

DN:It’s interesting to think that if sentences have skeletons then different sentences are, in a sense, different animals. This would bring us back to rhythm, as they would all have a different rhythm, a different sound, because they would walk differently.

UKL:A different gait, right. Although all the sentences in a piece would also be following a certain underlying, integrating rhythm.

DN:Every so often in your book on writing, Steering the Craft , you have an opinion piece, and one of my favorites is about morality and grammar. You talk about how morality and language are linked, but that morality and correctness are not the same thing. Yet we often confuse them in the realm of grammar.

FROM

George Orwell’s 1984

• • •

“It was a bright cold day in April,

and the clocks were striking thirteen.”

UKL:The “grammar bullies”—you read them in places like the New York Times , and they tell you what is correct: You must never use “hopefully.” “Hopefully, we will be going there on Tuesday.” That is incorrect and wrong and you are basically an ignorant pig if you say it. This is judgmentalism. The game that is being played there is a game of social class. It has nothing to do with the morality of writing and speaking and thinking clearly, which Orwell, for instance, talked about so well. It’s just affirming that I am from a higher class than you are. The trouble is that people who aren’t taught grammar very well in school fall for these statements from these pundits, delivered with vast authority from above. I’m fighting that. A very interesting case in point is using “they” as a singular. This offends the grammar bullies endlessly; it is wrong, wrong, wrong! Well, it was right until the eighteenth century, when they invented the rule that “he” includes “she.” It didn’t exist in English before then; Shakespeare used “they” instead of “he or she”—we all do, we always have done, in speaking, in colloquial English. It took the women’s movement to bring it back to English literature. And it is important. Because it’s a crossroads between correctness bullying and the moral use of language. If “he” includes “she” but “she” doesn’t include “he,” a big statement is being made, with huge social and moral implications. But we don’t have to use “he” that way—we’ve got “they.” Why not use it?

DN:This difference between grammatical correctness and the ways language engages moral questions reminds me of this quote of yours: “We can’t restructure society without restructuring the English language.” That the battle is essentially as much at the sentence level as it is in the world.

UKL:As a freshman in college I read George Orwell’s great essay about how writing English clearly is a political matter. It went really deep into me. Often I’m simply rephrasing Orwell.

DN:It’s reflected in your work as well. I think of The Dispossessed , your novel about an anarchist utopia. There is no property in this imagined world and there are also no possessive pronouns. The world and the language of the world are reflecting back upon each other.

UKL:The founders of this anarchist society made up a new language because they realized you couldn’t have a new society and an old language. They based the new language on the old one but changed it enormously. It’s simply an illustration of what Orwell was saying.

DN:Lots of these rules of grammatical correctness that reflect some regressive tendencies in society, you call “fake rules.” In Steering the Craft , you talk about the importance of engaging with our tools, understanding the power of punctuation and understanding grammar, but also warn us to be careful not to fall for these fake rules. One of them is the generic pronoun “he” to refer to both men and women, what amounts to an erasure of women at the sentence level. Is it true that you’ve said that if you could rewrite Left Hand of Darkness , a book, way ahead of its time, about gender fluidity, you would make some changes like this on the sentence level?

UKL:Obviously it is unsatisfactory to call these genderless people “he” throughout the book, as I do (unless one of them goes into “kemmer” and gains gender, becomes genuinely if temporarily “he” or “she”). In 1968, “they” was simply not an option; no editor would have published the book. Soon after the book was written several novels came out using made-up pronouns to blur gender, but I couldn’t do it; I can’t do that to English. So what to do? I rewrote a chapter of Left Hand of Darkness making everybody “she” instead of “he,” and it is interesting to read it after having read the “he” version. But it’s not right either. They aren’t “she.” They’re “they.” And we can’t use “it.” I envy the Finnish, and I think the Japanese at least in some respects, that they can speak genderlessly.

FROM

The Dispossessed

• • •

There was a wall. It did not look important. It was built of uncut rocks roughly mortared. An adult could look right over it, and even a child could climb it. Where it crossed the roadway, instead of having a gate it degenerated into mere geometry, a line, an idea of boundary. But the idea was real. It was important. For seven generations there had been nothing in the world more important than that wall.

Like all walls it was ambiguous, two-faced. What was inside it and what was outside it depended upon which side of it you were on.

FROM

The Left Hand of Darkness

• • •

And I saw then again, and for good, what I had always been afraid to see, and had pretended not to see in him: that he was a woman as well as a man. Any need to explain the sources of that fear vanished with the fear; what I was left with was, at last, acceptance of him as he was. Until then I had rejected him, refused him his own reality. He had been quite right to say that he, the only person on Gethen who trusted me, was the only Gethenian I distrusted. For he was the only one who had entirely accepted me as a human being: who had liked me personally and given me entire personal loyalty, and who therefore had demanded of me an equal degree of recognition, of acceptance. I had not been willing to give it. I had been afraid to give it. I had not wanted to give my trust, my friendship to a man who was a woman, a woman who was a man.

DN:Just as you’ve pointed out the erasure of women at the sentence level you’ve also voiced concerns about the ways in which women writers get disappeared from the conversation, particularly when it comes to entering or not entering the canon. I think in one conversation someone asked you for examples and you mentioned Grace Paley as someone sliding out of the conversation.

Читать дальше