Whether Skinner was out to discomfit the Rumbaughs and prove that pigeons are as smart as chimps, or whether both were out to prove that pigeons and chimps are as smart as people, or at least that their intelligences are not qualitatively different, we must admire the skill of both teams of investigators in teaching communication skills. But what has been called into question in these and like experiments is the use of words such as language, symbols, sentences to describe this kind of communication. Investigators such as Terrace and Sebeok have shown that such communication does not bear the test of language in the human sense, e.g., having a rule-governed syntax. One of the weaknesses of semiotics is the all-too-frequent use of words like language and sentence in a loose analogical sense.

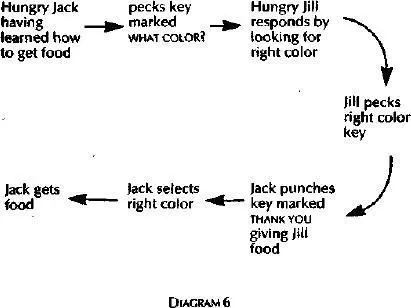

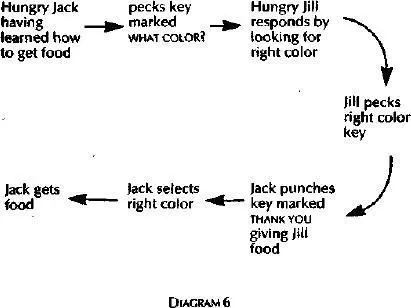

This argument aside, what matters here is that these communications in Skinner’s pigeons and the Rumbaughs’ chimps can be understood perfectly well by Peirce’s familiar dyadic model, as a sequence of interactions or dyads:

This sequence can of course be broken down into smaller dyads, e.g., interactions between Jack’s conditioned neurones, electrical discharges along the efferent nerves leading to Jack’s pecking muscles, and so on.

An African gray parrot named Alex at Purdue University has been taught to call forty objects by name, identify five colors, and distinguish between a square, a triangle, and a pentagon. When he wants to return to his cage, he says, “Wanna go back.”

Many people, including some scientists, like to speak of the “language” of the Rumbaughs’ chimps, Skinner’s pigeons, and the Purdue parrot, to say nothing of the song of the humpback whale. These communications, however, bear little if any resemblance to human language. The former can be understood as dyadic events not qualitatively different, albeit much more complex, from other dyadic events in the Cosmos. The latter cannot be so understood.

V

Extremely recently in the history of the Cosmos, at least on the earth — perhaps less than 100,000 years ago, perhaps more — there occurred an event different in kind from all preceding events in the Cosmos. It cannot be understood as a dyadic interaction or a complexus of dyadic interactions.

It has been called variously triadic behavior, thirdness, the Delta factor, man’s discovery of the sign (including symbols, language, art).

This phenomenon occurred in the evolution of man. It may have occurred elsewhere in the Cosmos, or it may have occurred in other creatures on earth. We do not know. But it is not known to have occurred elsewhere in the Cosmos and it has not been proved — despite heroic attempts with chimps, gorillas, and dolphins — to have occurred in other earth species.

The present argument does not require that triadic behavior be unique in man. Perhaps it is not. Semiotics proposes only that where triadic behavior occurs, certain new properties and relationships also come into existence,

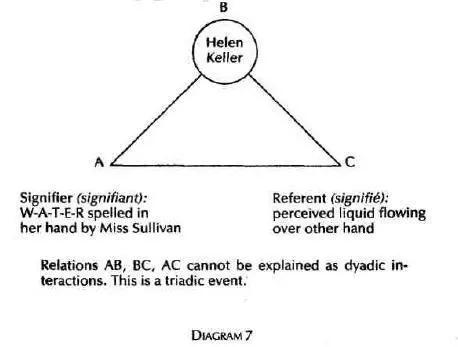

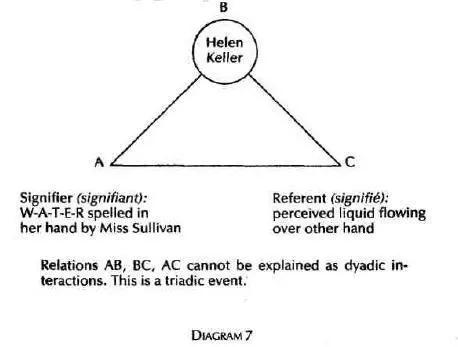

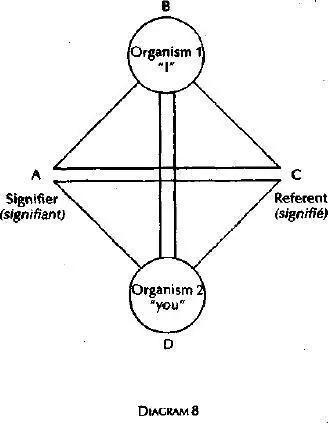

Triadic behavior is that event in which sign A is understood by organism B, not as a signal to flee or approach, but as “meaning” or referring to another perceived segment of the environment:

This triad is irreducible. That is to say, it cannot be understood as a sequence of dyads, as could the events, say, when Miss Sullivan spelled C-A-K-E into Helen’s hand and Helen went to look for cake — like one of Skinner’s pigeons.

At any rate, a triadic event has occurred and it is unprecedented in the Cosmos. Thus, there is a sense in which it can be said that, given two mammals extraordinarily similar in organic structure and genetic code, and given that one species has made the breakthrough into triadic behavior and the other has not, there is, semiotically speaking, more difference between the two than there is between the dyadic animal and the planet Saturn.

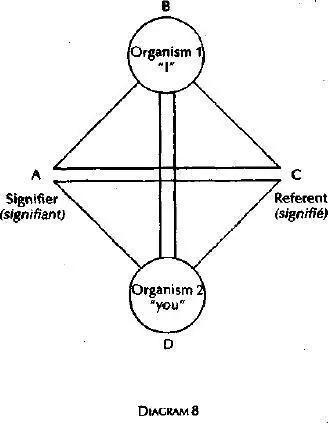

Certain new properties appear. For example, all triadic behavior is social in origin. A signal received by an organism is like other signals or stimuli from its environment. But a sign requires a sign-giver. Thus, every triad of sign-reception requires another triad of sign-utterance. Whether the sign is a word, a painting, or a symphony — or Robinson Crusoe writing a journal to himself — a sign transaction requires a sign-utterer and a sign-receiver.

Other new properties appear, such as the relation between the utterer and the receiver, which are subject to such familiar variables as “intersubjectivity” (I-thou) and “depersonalization” (I-it).

A particularly mysterious property is the relation between the sign (signifier) and the referent (signified). It is expressed by the troublesome copula “is,” when Helen said that the perceived liquid “is” water (the word). It “is” but then again it is not. Herein surely is the root of all the troubles Stuart Chase spoke of when he said that his cat had no dealings with such a relationship and therefore was smarter or at least saner than humans.

Another unique property of the sign-user, of special significance here, is that as soon as he crosses the triadic threshold, he not only continues to exist in an environment but also has a world.

The world of the sign-user is not identical to its environment or the Cosmos.

Relation AC — your giving a name to a class of objects to make a sign, and my understanding or misunderstanding of such a naming — cannot be understood as a dyadic interaction.

Relation BD — the I-you intersubjectivity of an exchange of signs — cannot be understood as a dyadic interaction.

These are two conjoined triadic events which always happen in any exchange of signs, whether in talk, looking at a painting, reading a novel, or listening to music. It allows for such peculiar properties of triadic events as understanding, misunderstanding, truth-telling, lying.

VI

The first Edenic world of the sign-userMiss Sullivan (writing of Helen Keller): As the cold water gushed forth, filling the mug, I spelled “w-a-t-e-r” in Helen’s free hand. The word coming so close upon the sensation of cold water rushing over her hand seemed to startle her. She dropped the mug and stood as one transfixed. A new light came into her face. She spelled “w-a-t-e-r” several times. Then she dropped on the ground and asked for its name and pointed to the pump and the trellis, and suddenly turning around asked for my name. I spelled, “Teacher.” Just then the nurse brought Helen’s little sister into the pump-house, and Helen spelled “baby” and pointed to the nurse. All the way back to the house she was highly excited, and learned the name of every object she touched, so that in a few hours she added thirty new words to her vocabulary. Here are some of them: Door, open, shut, give, go, come, and a great many more. *Roger Brown and Ursula Belhigi (writing in “Three Processes in the Child’s Acquisition of Syntax”): Some time in the second six months of life most children say a first intelligible word. A few months later most children are saying many words and some children go about the house all day long naming things ( table, doggie, ball, etc.) and actions (play, see drop, etc.) †Philip E. L. Smith: Having inherited from more primitive ancestors large and efficient brains, as well as a serviceable technology, these new humans proceeded to make a quantum jump greater than anything seen before in a comparable length of time. In esthetics, in communication and symbols, in technology and adaptive efficiency, and perhaps in newer forms of social organization and more complex ways of viewing their fellows, these first modern men went on to effect a transformation worldwide in its impact. *

Читать дальше