A Semiotic *Primer of the Self

A Short History of the Cosmos with Emphasis on the Nature and Origin of the Self, plus a Semiotic Model for Computing Impoverishment in the Midst of Plenty, or Why it is Possible to Feel Bad in a Good Environment and Good in a Bad Environment

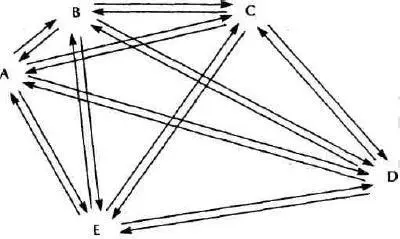

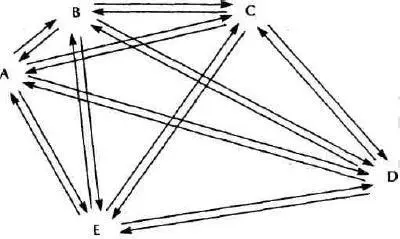

From the beginning and for most of the fifteen billion years of the life of the Cosmos, there was only one kind of event. It was particles hitting particles, chemical reactions, energy exchanges, gravity attractions between masses, field forces, and so on. As different as such events are, they can all be understood as an interaction between two or more entities: A↔B. Even a system as inconceivably vast as the Cosmos itself can be understood as such an interaction:

DIAGRAM 1

Every element in the Cosmos is in interaction with every other element. The elements and systems of the Cosmos are still in interaction whether we are speaking of the radiation of energy in the electromagnetic spectrum or the attraction of gravity between bodies. In a sense, astrologers are right. The planet Saturn has an influence on me; it exerts a small gravitational attraction. I in turn exert a slight pull not only on the planet Saturn but upon the entire M31 galaxy in Andromeda. When I take a single step, I affect the rotation of the earth.

II

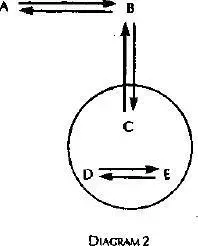

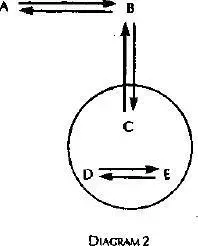

Some three and a half billion years ago, organic life began on this planet, perhaps earlier on other planets, perhaps not at all. A discharge of lightning might have caused the formation of organic molecules in the primordial soup, molecules which sooner or later happened to replicate themselves, though it is difficult to imagine how these events could have occurred accidentally. Perhaps there was another cause. Perhaps God was the cause. We do not know. At any rate, a new kind of system came into being, the organism. It had the extraordinary property of maintaining its internal milieu, its homeostasis, and of reproducing itself. Yet, different though it was from other systems, events within the organism and across the membrane of the organism as well as events in its environment could still be understood as the same kind of events — dyadic interactions which had occurred before:

The interactions of organisms with each other, whether sexual, combative, or predatory, could be similarly understood:

It is all very well to speak of the wonders of the Cosmos as testimony to the glory of God, and it may in fact be true, but it, the Cosmos, is hardly perceived as such in modern technological societies. For most scientists, it seems fair to say, these same wonders, including the behavior of organisms, can be explained as an interaction of elements. The wonder to the scientist is not that God made the world but that the works of God can be understood in terms of a mechanism without giving God a second thought. Is it not indeed more wonderful to understand the complex mechanisms (dyads) by which the DNA of a sperm joins with the DNA of an ovum to form a new organism than to have God snap his fingers and create an organism like a rabbit under a hat?

The real wonder is not that the Cosmos is now seen as wonderful but that it is not. Despite its inconceivable vastness, it is seen not as wonderful but as something that can be explained as a dyadic system.

III

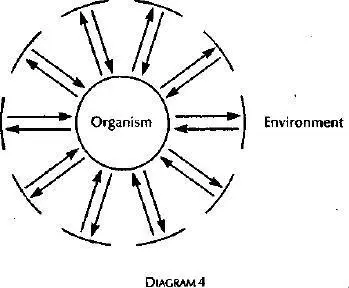

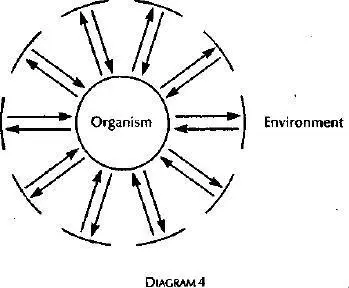

It became useful to think of an organism as an open system which through the selective processes of evolution had developed a genetic code which enabled it to maintain an internal steady state (homeostasis) in a changing environment and to reproduce itself. Thus, all the elements and events in the Cosmos, including other organisms, could be thought of as the environment of the organism. The organism “responded” to those segments of its environment to which, through evolution, it had become genetically coded — hardwired — to respond: eating, fighting, avoiding some, approaching and mating with others. Those segments of the environment which were without biological significance were ignored:

There are many gaps in the environment of an organism. This is to say that though there may be an interaction between the mass of the organism and the mass of Jupiter, the organism does not respond to Jupiter in any observable way. Yet the organism, as in the case of a migrating bird, has been shown to respond to the magnetic field of the earth or the position of the sun.

IV

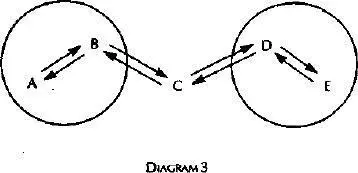

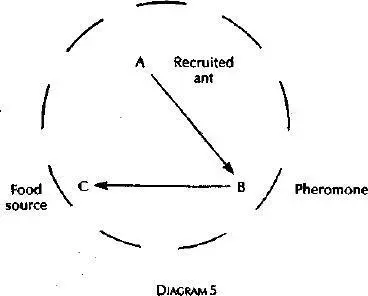

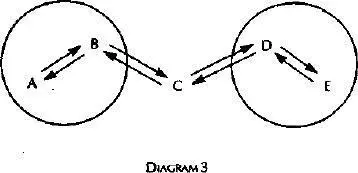

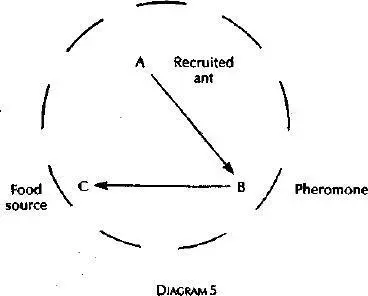

An organism may also, either by being genetically coded or by learning — that is, by modifying certain neurones in its central nervous system — respond to certain signals in its environment by a behavior oriented toward other segments of the environment. Thus, a Texas leaf-cutting ant which discovers a food source too big to move will deposit a trail of pheromones on the ground, which other ants will follow for several hundred meters from the nest:

The Texas leaf-cutting ant is genetically programmed so to respond. But Pavlov’s dog — or any other mammal exposed to certain changes in its environment — can learn to respond to a signal in an appropriate manner — by eating, fleeing, or fighting — through modification of cells in its central nervous system.

A gorilla (A) in its natural state can utter one of a dozen or so vocal signals which are responded to by other gorillas (B, C, …) in an appropriate fashion — e.g., the bark wraagh is a signal of a sudden alarming situation, such as unexpected contact with buffalo, which signals flight in other gorillas.

The chimpanzee Lana has been taught by the Rumbaughs, through a learning program of rewards, to punch differently marked keys of a computer and “ask” for food, liquids, music, etc.

Next the Rumbaughs taught two chimpanzees to communicate with each other, e.g., one chimp punching a marked key to ask another chimp for a certain food to which the importuned chimp had access. The Rumbaughs called the marks on the computer keys “symbols” and the transaction between the two chimps “the first successful demonstration of symbolic communication between two nonhuman primates.”

Whereupon B. F. Skinner showed that two domestic pigeons (Columba livia domestica) could learn spontaneously to use such “symbols” to communicate with each other. The two pigeons, named Jack and Jill, could conduct a “conversation.” Jack was the observer and Jill the informer. Jack and Jill first learned to associate marked keys with three colors. Jill was taught to “name” three colors to respond to the keyboard-question “What color?” Jack was taught to select the color corresponding to the name. When the pigeons were correct, they were rewarded with grain. Then Jack learned to ask Jill for a color name by depressing the WHAT COLOR? key. Then Jill looked behind a curtain at a color hidden from Jack. Then, while Jack watched, Jill selected a “symbolic name” for the color. When Jill was right, Jack rewarded her by pushing the THANK YOU key. Then, while Jill moved to her reward, Jack selected the right color. Then Jack was rewarded.

Читать дальше