“As though drawn to the city by a fatal fascination, German troops kept pouring in to 3rd Armored Division road blocks,” the unit recorded. “Tanks and tank-destroyers enjoyed a brief field day, the crews firing their big guns until the tubes smoked.”

The American victory was resounding.

The 1st Infantry Division, the “Big Red One,” would come in to finish what the 3rd Armored had begun, and out of the 30,000 Germans who came to Mons, 27,000 would leave as prisoners, including three generals and a lowly sailor who had hitchhiked from his port in western France.

“Probably never before in the history of warfare has there been so swift a destruction of such a large force,” concluded the 3rd Armored Division history.

—

The turret floor was slippery with bullet casings as Clarence rose halfway from the commander’s hatch and eyed the sunken road.

Reinforcements had arrived in the form of more doughs, but it was too late. Paul’s lifeless body lay at the medics’ feet. Clarence silently pleaded for his friend to cough or flinch or show any sign of life.

That time had passed.

The medics packed up their bags to move on. “Can we take him back with us?” Clarence asked with a trembling voice from his perch in the turret.

The medics were sympathetic. “Graves Registration will be along soon.”

At the words, Clarence buried his face in his sleeve. Paul’s body. The field of dead Germans. He sank down into the turret and shut the covers.

—

The Sherman belched a grunt of smoke before rolling from the sunken road, bound for the bivouac.

Inside, Clarence folded over in the commander’s seat and wept. The night before, he and Paul had shared a thermos of cold coffee. And now Paul was dead. It had not even been twenty-four hours. But for a Spearhead tanker, this was just another day in the hard-fighting division that would suffer more men killed in action than the 82nd or 101st Airborne Divisions, and would lose the most American tanks in World War II.

And Germany was yet to come.

Five days later, September 8, 1944

Eighty-five miles southeast—Luxembourg

The thunder of heavy artillery rippled over the village of Merl, on the western outskirts of Luxembourg City.

Beneath leafy trees on a country lane, a young German tank crewman performed a balancing act as he carried five mess kits brimming with food.

Shells burst in the fields to his left, tossing embers and vaporized dirt into the morning sun.

Private Gustav Schaefer watched the explosions in awe. Far beyond the forests that ringed the fields, the Americans were firing blindly, hitting nothing, putting on a fireworks show seemingly just for him.

Gustav Schaefer

Barely five feet tall, Gustav resembled a child in camouflaged tanker coveralls. He was seventeen, blond, and square-jawed, with a disposition so quiet that his lips seldom moved to speak. His dark eyes did his talking for him—there was nothing they couldn’t convey with a glance. On this, his first day in combat, his eyes spoke volumes. Despite the explosions detonating nearby, Gustav was having fun.

The thunderclaps grew louder as they landed closer and closer.

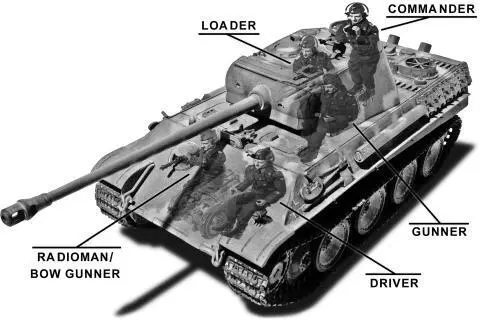

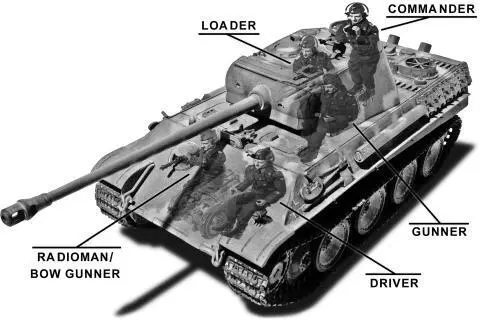

Gustav increased his pace to a brisk walk, but refrained from running. As the crew’s radioman, who doubled as the bow gunner, he was known as the “girl for everything,” because his role also entailed fetching food and fueling the tank. Gustav accepted the tasks—and the title—without complaint. Hot stew rocked in the mess kits, the crew’s meager rations for the day. He couldn’t afford to spill a drop.

About one hundred yards up the road, his crewmates were running back to their tank, which was parked in the shade alongside a hedge. A web of hand-cut branches served as camouflage and further masked the sharp lines of a Panther. Before disappearing inside, the men shouted for Gustav to hurry.

Another thunderclap rippled. This one was so close that the shockwave slapped Gustav’s cheek. Brown clouds of vaporized dirt floated closer than before. He broke into a jog, holding the mess kits high as the stew sloshed inside. Another thunderclap shoved him. He felt its heat and smelled burnt powder.

The tank was bouncing in his vision, he was nearly there. He had only about forty yards farther to go and he’d be safe, a returning hero with the crew’s rations. But before he could make it, the field to his left exploded.

A blinding flash. A deafening crack. An invisible hand seemed to pick him up and sweep him across the road into a ditch.

Gustav opened his eyes to a rain of dirt. His eardrums throbbed with pain and he felt a burning sensation on his chest.

I’m hit!

He pawed at his coveralls and his hand came away wet, which sent him into an even greater panic. Then he saw the spilled mess kits oozing with stew and knew what he was feeling. Another shockwave rippled overhead. He had to move before he ended up a casualty along with the rations.

Scooping up his black overseas cap, Gustav bolted for the tank. Thirty yards away, twenty, ten…

With an athletic leap he grabbed the gun barrel and swung himself onto the frontal armor. Scampering higher, he parted the camouflage branches and entered his hatch.

Panther G

Safe in the tight, oil-scented confines, he collapsed against his machine gun. The others couldn’t see him. A wall of spare shells, stacked horizontally, separated him from the driver to his left, and more shells obscured the three men in the turret basket behind him. It was too soon to show them his fear.

They were all veterans who knew him as Bubi, or little boy. After their units had been devastated on the Eastern Front, they, together with rookies like Gustav, had been placed into the 2nd Company of the newly formed Panzer Brigade 106, and sent to Luxembourg City, just twelve miles west of the German border.

With a strength of forty-seven vehicles—thirty-six Panthers and eleven Jagdpanzer IV self-propelled guns—the brigade’s orders were hopelessly overreaching: delay the American advance at any cost.

Like a U-boat crew in the ocean depths, the men listened to the explosions thumping outside. Gustav eyed the hull’s ceiling, expecting it to burst at any moment. He would have given anything to be back on his farm in Arrenkamp, in the windswept fields far in the German north.

Home was a humble ranch lit by candles, with a stable attached to the entrance and swallows fluttering inside. Abiding by folklore tradition, his father always cut a hole in the roof so the birds could build their nests within the walls and bring the family luck.

Gustav’s parents had one bedroom while Gustav and his younger brother shared the other with their grandparents. His best friend was his grandmother Luise. A short, sturdy woman who wore her blond hair in a bun, she would read fairy tales to the boys, including Gustav’s favorite, “Snow-White and Rose-Red.” It was a simple life, but far better than in any tank.

—

No one spoke after the shelling tapered to nothing. Was that it?

The tank wasn’t big enough for Gustav to hide forever. Sooner or later his crewmates would notice that he was wearing their supper.

His gut instinct told Gustav to blame the kitchen crew. They had parked a half mile from the tanks to protect their own necks.

Читать дальше

![Adam Turvi - Возвращение [СИ]](/books/422738/adam-turvi-vozvrachenie-si-thumb.webp)