This Sherman was a “75,” owing to its 75mm gun, but to Clarence’s crew it had a name—Eagle—and someone had painted an eagle head on each side of the hull. For recognition purposes, every tank’s name in Easy Company began with the letter E .

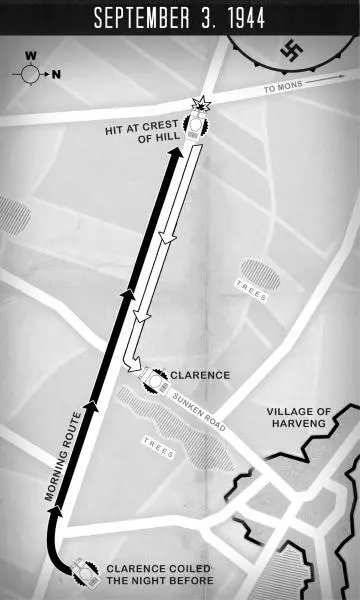

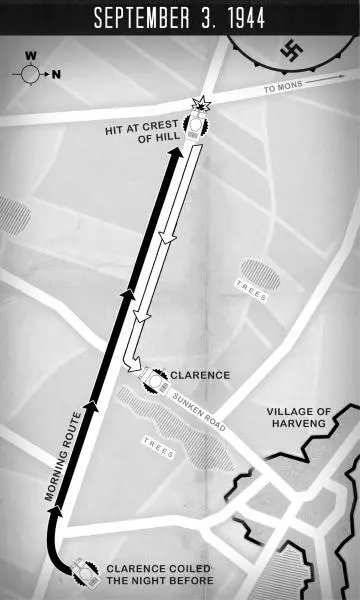

Paul raised his field glasses to his eyes and studied the terrain ahead. The tank was bound for the tree-lined ridge, the source of the nighttime commotion.

—

One by one, the neighboring Shermans vanished from sight. They plunged into patches of woods or slipped around edges of fields and set their guns toward the enemy.

While Clarence and the crew inside assumed that a mighty force still surrounded them, Paul could see that his tank was alone. Every swaying tree, every shifting shadow now assumed a sense of hostile intent.

Paul held his course. His orders were to set a roadblock atop the tree-lined ridge where the German tanks had originated the night before.

His crew hadn’t been the only one to experience a fraught encounter. At one American bivouac, a fatigued MP had directed a Panther tank off the road and into a parking space meant for Shermans. The German crew realized their mistake and came out with their hands up.

—

As the tank barreled toward the ridge, Clarence pestered Paul on the intercom.

“Are you sure?” Clarence asked, again, from his perch in the gunner’s seat.

Paul wasn’t deviating from his story. “Don’t worry, they all got out.”

Paul had assured Clarence that the German crew escaped the Mark IV alive, but Clarence had a suspicion that his friend was just trying to protect him. Paul had done it before.

It happened after the last furlough before the unit shipped overseas in September 1943. Clarence had been on a date in a park in Reading, Pennsylvania, and was so enjoying the young woman’s company that he missed the bus back to base. By the time he hitchhiked back, he’d been declared AWOL.

When Easy Company arrived in the English village of Codford, Clarence’s punishment was handed down. Every night after the evening meal, Clarence was ordered to cut the grass around the company’s three Quonset huts with just the butter knife of his mess kit. He’d take a fistful of grass, saw away, and then move to the next clump, from about seven to eleven each night.

Paul wasn’t one to frequent the local pub or foray on a pass to London, so he’d sit against a Quonset hut and keep Clarence company while he worked. Over the course of three months, they talked. Clarence learned that Paul’s father had been an engineer for Georgia Southern Railroad and that his mother was a full-blooded Cherokee and convert to Evangelical Christianity.

When Paul was in sixth grade, his father had died, so he quit school and became a clerk at a general store to support his mother and sisters. Surprised by Paul’s keen mind for numbers, the store owner soon had him doing the bookkeeping.

A few tankers from the company found Clarence’s punishment amusing and took to urinating behind the huts on grass that Clarence was due to cut. Paul called them together. “It’s the latrine that separates us from animals,” he said.

That put an end to it.

—

At the crest of the ridge, Clarence’s periscope filled with sky as the mighty tank’s nose lifted from the road.

He’d never get to see what lay on the other side.

As the tank settled forward, a crack rapped the gun barrel with a spit of sparks. Clarence reeled from the periscope. We’re hit! A gonglike sound resonated through the steel walls.

Paul dropped into the turret and screamed for the driver to reverse. Gears ground and the tank tilted and backtracked downhill. At the base of the hill, Paul guided the driver backward into a sunken road lined by trees, until only the top of the tank was visible.

Paul and Clarence climbed out to inspect the damage. Atop the turret they froze at the sound of thunder in a perfectly blue sky.

A battle was raging beyond the nearby hills. Smoke rose into the sky, and P-47 fighter-bombers powered overhead, bound for a distant tangle of roads where German vehicles were reportedly snagged in a “delicious traffic jam.”

Clarence eyed the gun barrel with concern. A shell had struck the side and removed a scoop of metal before deflecting over the turret. A few more inches to the right and the shell would have come straight through his gun sight, killing him instantly. They had probably driven into the sights of an antitank gun—an enemy tank would surely have maneuvered to take a second shot.

Clarence gave Paul the bad news. The gun barrel was likely collapsed internally, and if he fired, the shell could get jammed and its backblast could come into the turret, wiping out the crew.

That settled it. It was simply too risky to fire.

Back in the safety of the turret, Paul radioed Easy Company’s headquarters for permission to retreat. On the other end, a shaky voice reported that the Germans were attacking across a wide front, probing for holes in the lines. The situation had turned so dire that clerks and men from the supply train were being sent out to fight.

The orders to Paul were firm: “Hold your position.” Paul asked for reinforcements, anyone they could spare.

Transmissions were always broadcast throughout the tank, for the awareness of the crew, so it was clear to them all that the situation was desperate. Clarence asked the loader to go below and get extra ammo for the coaxial—a .30-caliber machine gun that was set on the loader’s side with its barrel protruding outside the gun shield, where it was fixed to fire wherever the main gun was pointed. A second trigger on Clarence’s footrest, left of the cannon trigger, would fire the coaxial.

Paul reviewed their roles. He and Clarence would cover the tree-lined ridge, while the bow gunner would guard the front with his .30-caliber machine gun, which projected from the tank’s frontal armor. The driver was to keep the engine running.

Paul rose from his hatch and swiveled the roof-mounted machine gun.

Everything revolved around him as the turret swung to the right then stopped sidelong from the tank. The main gun and coaxial elevated toward the ridge.

From between his partially open hatch covers, Paul took aim.

—

About two hundred yards away, on top of the ridge, the silhouettes of men appeared.

A dozen soldiers waded cautiously down the gentle slope as more soldiers appeared behind them. They spread out, clambering down the field in staggered groups. There were about one hundred of them, wearing German gray, some with green smocks. Sunlight beat down on their faces.

The turret slid beneath Paul; Clarence was tracking them too.

The enemy had come far enough.

Paul clenched his trigger, sending fire leaping from the muzzle. He worked his gun side to side as the bolt blurred and spat empty casings. Clarence’s coaxial added its earsplitting roar, its smoke rising in front of Paul.

The Germans fell in droves—many killed or badly wounded. Others pawed for cover in shallow gullies. A few fired back, their bullets snapping the air around Paul.

Inside the tank, Clarence held an eye to his 3x telescopic gun sight. It was kill or be killed—them or his family. Clarence’s foot came down, the coaxial thumped, then he turned a handle, an electric motor whined, and the turret swung his reticle to the next target.

A German working the bolt of a rifle. An officer screaming into a radio. A soldier running away. Clarence’s foot came down again. The action was so fast, there was no discerning.

Читать дальше

![Adam Turvi - Возвращение [СИ]](/books/422738/adam-turvi-vozvrachenie-si-thumb.webp)