Alan Jolly’s comments form a useful postscript to this section. Jolly commanded the 144th Royal Armoured Corps (RAC) in the north-west Europe campaign. This unit was converted to the 4th Royal Tank Regiment before the end of the war to replace the unit captured in Tobruk. Jolly himself had a distinguished military career and was promoted general. In the epilogue to his book Blue Flash , he reflects on some of the observations he had made and lessons he had learned during the course of his military career. In discussing the use of tanks he notes:

There are two basic purposes for which tanks exist and for which at present [1952] there are no substitutes. The first of these is to provide direct fire support for infantry as opposed to the indirect fire of artillery. Artillery provides a greater weight of fire but can only deal with an area target and must therefore cease during the last 150 yards of the infantry’s advance to their objectives. This is where they usually suffer the bulk of their casualties from small arms fire, and it is here that the tank must fill in the gap by shooting with weapons of pin point accuracy up to the moment that the infantry close with their enemy.

The second basic purpose for which the tank exists is to provide the hard core of the mobile portion of an army. This faster portion which provides the decisive action in battle is composed of armoured divisions, the tanks of which provide a concentration of mobile fire power which can disrupt, disorganise and pursue an enemy whose front has been broken or cracked by the slower infantry divisions and their supporting armour and artillery. The tank has one other significant purpose and that is to fight other tanks. However, the two fundamental purposes are to provide direct fire support of a nature which cannot be produced by artillery and to form the hard core of the mobile portion of an army.

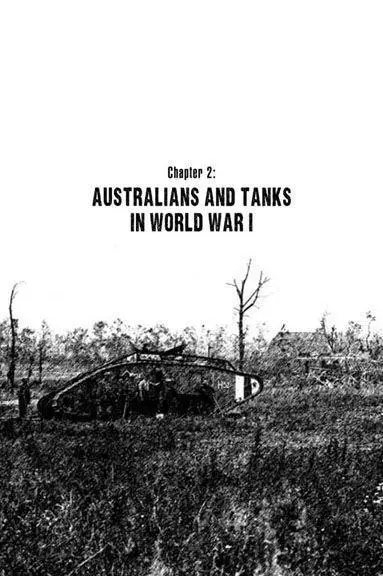

Chapter 2:

AUSTRALIANS AND TANKS IN WORLD WAR I

Despite the fact that there were no Australian tank units in World War I, the AIF in France gained considerable experience working with tanks. Three significant actions saw Australian infantry supported by British tanks: the First Battle of Bullecourt, 10–12 April 1917; the Battle of Hamel, 4 July 1918; and several battles during the Hundred Days towards the end of the war, particularly the action fought on 8 August 1918, the German Army’s ‘Black Day’.

First Bullecourt was a disaster for the 4th Australian Infantry Division, and a sorry showing for the British tanks. As a result, the Australians became very mistrustful of tanks in any form, and took more than a year to be persuaded to use them again in the attack on the village of Hamel. By this time tanks were far more reliable, and the Tank Corps as a whole had proven how effective it could be at the Battle of Cambrai on 20 November 1917. 1

The Battle of Hamel was superbly planned and executed by the Commander of the 1st Australian Corps, Lieutenant General Sir John Monash. He integrated the use of infantry, artillery, tanks, aircraft, and other services so that all objectives were gained without excessive loss in just over an hour and a half.

The success of Hamel reinforced the Allied High Command’s new confidence in tanks and, one month after Hamel, the opening assault of the Battle of Amiens employed almost all the British tanks available. This chapter describes the three actions of First Bullecourt, Hamel, and Amiens, and illustrates that, by the end of the war, the Australians were enthusiastic and knowledgeable about the capabilities of tanks, even if there were no Australian tank units as yet.

Accounts of these battles were often written from the viewpoint of the infantryman, the tankman, or soldiers from the other arms. Quite often, an account by one arm of the service barely mentions the operations of the others, providing a one-sided impression of the action. However, all actions in which the Australians took part in France have been meticulously and objectively recorded by Charles Bean, Australia’s official correspondent during World War I and author of six of the twelve volumes of The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914 to 1918 . 2

First Bullecourt

The First Battle of Bullecourt 3resulted from a decision to use the Fifth British Army, commanded by General Gough, on the right of a major thrust by the First and Third British Armies. 4Gough’s task was to advance to the Hindenburg Line just to the north of the village of Bullecourt capturing the village during the advance. The 4th Australian Infantry Division was part of the Fifth Army.

On 9 April 1917 the First and Third British Armies advanced towards Vimy and Arras. The relative ease of the push led Gough to believe that the Hindenburg Line was less strongly manned than previously considered. Gough ordered his Corps Commanders to send patrols forward to the Hindenburg Line, and if they could establish themselves in the line, to reinforce these with larger forces and advance further.

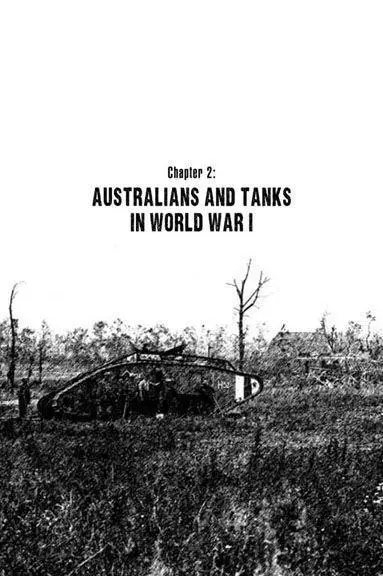

Tank in mud, Flanders. This scene is typical of the Flanders countryside after shelling and rain. It was the area where tanks were desperately needed but, because of their mechanical unreliability and the appalling terrain, they all too often let the infantry down (NAA image No. B4260, 3 Barcode 4167035).

General Gough had been allocated 11 Company of D Battalion Tank Corps (at that time known as the Heavy Branch of the Machine Gun Corps). The Company Commander, Major W.H.L. Watson, planned to use his tanks to assist the Fifth Army to overcome a shortage of artillery for destroying the wire defence works. 5His tanks would advance en masse without a barrage, steal up on the Hindenburg Line and enter the German trenches. Watson took this plan to his Commanding Officer (CO), Lieutenant Colonel Hardress Lloyd, who was sufficiently impressed to take the plan, with Watson in tow, to General Gough.

Gough approved the plan, and decided to attack with tanks supporting the Australian infantry the next morning. There were several problems with this attack: the Australians had not previously worked with tanks; D Battalion had been formed only at the beginning of 1917; the tank crews had trained in the back area in France, but with far too few tanks for adequate practice; their tanks were mainly Mark Is, which were still unreliable and whose armour was not bulletproof; Major Watson’s tank officers, with two exceptions, had neither experience nor skill; and there was very little time for preparation and reconnaissance.

Thus the 4th Australian Division was to be supported by a company of tanks whose men and officers were inexperienced and unskilful, and whose tanks were very slow and extremely unreliable. It was not surprising that, from the tanks’ perspective, the battle was a fiasco and, from the infantry’s point of view, it was a disaster.

On 10 April the tanks were so late in reaching the start line that the operation had to be postponed until the next day. On 11 April the tanks were again late, and not a single tank survived the opening attack. Dazzle painting had been abandoned as useless, and all were now the standard mud-brown. Against the snow, the tanks showed up admirably for the German gunners. As they moved slowly forward, nine were picked off almost at once, one of them having come to a halt with clutch trouble. The armour in which they had trusted proved useless. Even small arms fire riddled the hulls.

Читать дальше