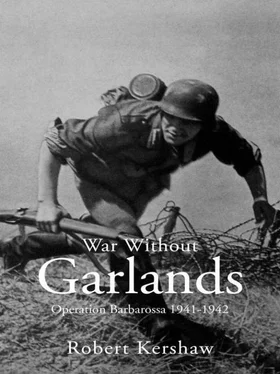

Robert Kershaw - War Without Garlands

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Kershaw - War Without Garlands» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: Hersham, Год выпуска: 2010, ISBN: 2010, Издательство: Ian Allan Publishing, Жанр: military_history, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:War Without Garlands

- Автор:

- Издательство:Ian Allan Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- Город:Hersham

- ISBN:978-07110-3590-1

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

War Without Garlands: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «War Without Garlands»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

War Without Garlands — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «War Without Garlands», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

All along the frontier with the Soviet Union and occupied areas German troops began to move up to their final assault positions. ‘I was with the leading assault wave,’ announced Helmut Pabst, an artillery NCO with Army Group Centre. His diary reveals snapshots of the final moments. ‘The units moved up to their positions quietly, talking in whispers. There was the creaking of wheels – assault guns.’ Such images remained permanently etched in the memories of survivors for the rest of their lives. Finally the infantry deployed. ‘They came up in dark ghostly columns and moved forward through the cabbage plots and cornfields.’ (21)Having reached their final attack positions, they spread out into assault formation. Men lay in the undergrowth listening to the sound of insects and croaking frogs along the River Bug, straining their ears to hear sounds from the opposite bank. Some were breathless, tense, waiting for the release of the opening salvo.

Rearwards, by the airstrip at Maringlen in occupied Poland, Dominik Strug, the Polish labourer, recalled, ‘it was two o’clock at night when the engines started to turn over.’ The air base was humming with activity, subdued lights showed here and there and the smell of high octane became apparent as clouds of exhaust began to disperse on the breeze. He went on, ‘We didn’t have a clue what was going on. Later we learned the Germans had started a war against the Russians.’ Spectre-like black shapes lumbered into the air, gathered and began to move purposefully toward their objectives. Strug, gazing into the distance, attempted to discern some pattern to this activity. They flew eastward. ‘Everything went towards Brest [-Litovsk], Brest, Brest… ’ (22)

Chapter 2

‘Ordinary men’ – The German soldier on the eve of ‘Barbarossa’

‘This drill – Ach! inhuman at times – was designed to break our pride, to make those young soldiers as malleable as possible so that they would follow any order later on.’

German soldier‘Endless pressure to participate’

Every conscript army is a reflection of the society from which it is drawn. The Wehrmacht in 1941 was not totally the image of the Nazi totalitarian state: it had, after all, only recently developed from the Weimar Reichswehr. It was, however, in transition. The process had begun in 1933. Progress could be measured in parallel with the economic and military achievements of the Third Reich. Blitzkrieg in Poland, the Low Countries and France had brought with it heady success. The German Wochenschau newsreel showing Hitler’s triumphant return from France showed him at the height of his power. Shadows thrown up by the steam-driven express train, Nazi salutes from solitary farmers en route juxtaposed against the sheer size of hysterical crowds greeting his return in Berlin have a true Wagnerian character. Children dressed in Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth) uniforms wave gleefully from lampposts. Adoring breathless women are held back by SS crowd-controllers. Goering, standing with Hitler on the Reich Chancellery balcony, is visibly and emotionally impressed by the roaring crowd whose cheering dominates the soundtrack.

The Wehrmacht’s morale, bathing in this adoration, was at its height. Wochenschau pictures of the French victory parade in Berlin, with close-ups of admiring women, and the pathos of a solitary high-heeled shoe left in the road as the crowd is pushed back from flower-bedecked troops, say it all. The troops were jubilantly received. Organisations and private people ‘render thanks to our deserving soldiers’, the newsreels opined. The wounded and those on leave received a torrent of presents and invitations. These were the good times. Schütze Benno Zeiser remembered on joining the army in May 1941:

‘Those were the days of fanfare parades, and “special announcements” of one “glorious victory” after another, and it was “the thing” to volunteer. It had become a kind of super holiday. At the same time we felt very proud of ourselves and very important.’ (1)

Success bred an idealistic zeal, producing an over-sentimental outpouring of the Nazi Weltanschauung that in modern democratic and more cynical times would appear positively alien. Leutnant Hermann Witzemann, a former theology student, marching with an infantry unit eastwards from the Atlantic coast, grandly announced to his diary:

‘We marched in the morning! Over familiar roads billeting in familiar village quarters. Infantry once more on French roads, Infantry in wind and rain, tired and irritable in wretched quarters, longing for the homeland all the time. The Reich’s Infantry! German Infantry. I lead the first platoon! In nomine Dei! [ In God’s Name! ]’ (2)

The postwar generation has had enormous difficulties reconciling and identifying with soldiers who clearly believed in God on the one hand and were seemingly decent human beings, yet on the other appeared receptive to a racist philosophy that enjoined them to disregard international law and the laws of armed conflict. One German soldier after the war, removed from the prevailing conditions that shaped and moulded him, gave an exasperated and often misconstrued view of the ‘Landser’ (the German equivalent of the British ‘Tommy’) on the eve of ‘Barbarossa’:

‘For me, it was a matter of course to become a soldier. Voluntary – not obliged to eh! If I hadn’t been called up I would have reported voluntarily in ’39. But not because of patriotism. I must say, all this sense of mission and “hurrah!” That wasn’t it at all. It was a family thing. My father was strict, but right.’

An element of racism formed an integral part of the society that had developed from the Imperial period, subdued to some extent during the Weimar Republic but more overt after 1933. He continued:

‘I was convinced we had to turn the Bolsheviks back. It has taken two World Wars – more! During peacetime alone the Bolsheviks had taken a human toll of eight million people. There you are! I found it shameful [ he raised his voice angrily ] that the German soldier is characterised as a murderer!’ (3)

To comprehend this statement, one must penetrate and attempt to identify some of the aspects and atmosphere that characterised the Nazi social fabric. Its outward manifestation was to reflect and impact upon the character and conduct of the German soldier. The soldier was under peer pressure to conform to the commonly accepted prejudices of his fellows, which had the effect of intensifying them. In a letter a month before the invasion of Russia, one conscript related a conversation with his parents:

‘While eating dinner the subject of the Jews came up. To my astonishment everyone agreed that Jews must disappear from the earth.’ (4)

Those disagreeing with such a notion were unlikely to identify themselves by standing apart from the crowd and speaking up. Indeed, the whole ethos of army service was about subjugating oneself to the whole. Such unquestioning obedience was likewise required by the Nazi state which the soldier served. It was, therefore, a question of individual choice and personal ethics in an environment demanding corporate obedience. The state in time insidiously corrupted values, which, if they were not changed, were effectively subdued. Margot Hielscher, an actress, explained:

‘I lived in Friedrichstrasse near the Kurfürstendamm [ in Berlin ] and many Jewish citizens lived in this district, so I experienced how they were treated by the shopkeepers and customers inside the shops. It was shameful. More shameful was the way we behaved. We were cowardly. We – unfortunately – simply turned away or failed to hear anything.’ (5)

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «War Without Garlands»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «War Without Garlands» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «War Without Garlands» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.