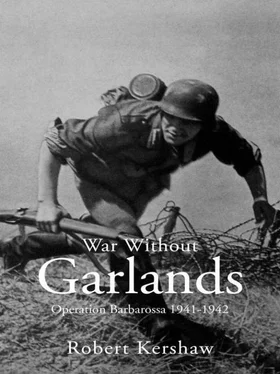

Robert Kershaw - War Without Garlands

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Kershaw - War Without Garlands» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: Hersham, Год выпуска: 2010, ISBN: 2010, Издательство: Ian Allan Publishing, Жанр: military_history, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:War Without Garlands

- Автор:

- Издательство:Ian Allan Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- Город:Hersham

- ISBN:978-07110-3590-1

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

War Without Garlands: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «War Without Garlands»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

War Without Garlands — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «War Without Garlands», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Army Group Centre, some 51 divisions strong, commanded by Generalfeldmarschall von Bock, provided the Schwerpunkt (main point of effort). As the most powerful of the two army groups north of the Pripet Marshes, its task was to encircle the enemy west of the upper Dnieper and Dvina near Minsk, thereby preventing an eastward escape. Apart from strong infantry forces, it contained the bulk of the mobile formations: nine Panzer, six motorised and one cavalry divisions forming Panzergruppen 3 and 2 under Generals Hoth and Guderian. Army Group North, a much smaller formation of 26 divisions commanded by Generalfeldmarschall von Leeb, was to attack Leningrad, link up with the Finns and eliminate all Russian forces from the Baltic. Its Panzer spearhead of three Panzer and two motorised divisions forming Panzergruppe 4 was commanded by General Hoepner. Army Group South’s 40 divisions, commanded by Generalfeldmarschall von Rundstedt, supported by 14 Romanian divisions and a Hungarian corps, was to attack out of Poland, supported by the five Panzer and two motorised divisions of Panzergruppe 1, led by General von Kleist. Its aim was to cut off enemy forces east of Kiev. Some 22 divisions, including two Panzer, were held in reserve across the front. The bulk of the armies, despite the inclusion of the mobile Panzer-gruppen, consisted of infantry. Armoured spearheads were expected to dictate the pace, otherwise they would advance at the same speed as Napoleon’s infantry almost 130 years before.

There appears to have been only a loose connection between logistic and operational planning. Hitler’s perception of Jewish-Bolshevik decadence led to generalisations concerning Soviet vulnerabilities and weaknesses. By November 1940 German logisticians were calculating they could at best case supply German forces within a zone approximately 600km east of the start-line. Yet strategic planners were setting objectives up to 1,750km beyond the frontier, and anticipating only six to 17 weeks to attain them. The planners and the Führer were expecting the norms achieved by the Blitzkrieg campaigns conducted in Poland, the Low Countries and France. The German soldier appeared capable of anything and had, indeed, already demonstrated so. Failure was a remote and as yet untested experience. Hitler confidently announced, ‘when “Barbarossa” is launched, the world will hold its breath.’

Tomorrow ‘we are to fight against World Bolshevism’

‘All the preparations indicated an attack against the Soviet Union,’ declared Schütze Walter Stoll, an infantryman. ‘We could hardly believe it, but the facts made the whole issue indisputable.’ It was not a welcome prospect. ‘We always retained the faint hope that it would not come to this,’ he said. Officers had been summoned to an early morning conference on 21 June. Such activity normally preceded something special. It did.

‘At 14.00 hours the whole company paraded. Leutnant Helmstedt, the company commander, grim-faced, stepped forward. He read the Führer’s proclamation to the Wehrmacht – now we knew the reason for all those secret preparations over the previous weeks.’ (1)

Unteroffizier Helmut Kollakowsky, another infantryman, received the news in similar fashion.

‘In the late evening our platoons collected in barns and we were told: “the next day we are to fight against World Bolshevism”. Personally, I was totally astonished, it came completely out of the blue, because the treaty between Russia and Germany had always been in my mind. My enduring memory on my last home leave was of the Wochenschau [ equivalent of Pathe-Newsreel ] I had seen, reporting the treaty was settled. I could not imagine that now we would fight against the Soviet Union.’ (2)

Although suspected by enquiring minds, the announcement of the impending invasion caused universal surprise among the rank and file. ‘One could say we were completely floored,’ confessed Lothar Fromm, an artillery forward observation officer. ‘We were – and I must emphasise again – surprised and in no way prepared.’ (3)Siegfried Lauerwasser, attached to a Luftwaffe unit moving up to his assembly area by train, was not informed. ‘We had no idea where we were going,’ he said, and tried to work it out by peering through the train window. ‘Then at a station the sign was in Polish.’ That night they reached their destination: brand-new 100-man barracks. A photo-intelligence officer guided them to their quarters. Once Lauerwasser and his comrades were gathered together, the officer, unable to contain himself, confided:

‘I’m not supposed to tell you boys, but at 04.00 it starts! [ Es geht los! ] We were shocked. What will happen to us? Then with dawn came the realisation there will be an attack and an invasion of Russia – and what emotions we had!’ (4)

‘We learned that the attack, Operation “Barbarossa”, was on, only a few hours before it started,’ commented Eduard Janke, with the 2nd SS Division ‘Das Reich’, ‘and that in a few hours we would be off.’ (5)

Knowledge of the decision was in many ways a relief. Uncertainty itself engendered nervousness. ‘The long wait is a real burden,’ complained a Gefreiter, ‘to which we have all been sentenced.’

‘Let’s get on with it’ was the pervasive emotion. The sooner the war got going again, the earlier it would finish. ‘When will the next battle come?’ wrote the same NCO. Letters home reflected such nervous anticipation. ‘We live each day and hour with tension,’ another wrote.

‘I can tell you much later. A lot of it will be incomprehensible. Hours waiting make the nerves taut, but it will eventually contribute to the victorious finale! And that one certainly wants to see pass us by as soon as possible.’ (6)

Many, perhaps the majority, simply viewed the decision with equanimity. They were soldiers after all. Officers and NCOs were confident and combat experienced. Some chose not to reflect and took it in their stride. Previous campaigns had been short, sharp and successful. ‘We were all strongly convinced that this war would also not last long,’ declared Gefreiter Erich Schütkowsky, a Gebirgsjäger (mountain infantryman).

‘Personally, I already had a funny feeling as we cast our eye over large unfolded Russian maps, and Napoleon’s fate came to mind. But these thoughts were soon banished with time. We had already experienced momentous successes, so nobody at this stage was contemplating defeat.’ (7)

‘Why are you losing hope that all this will not be over quickly?’ enquired one Gefreiter in response to home mail. ‘Once the thing with the Russians is in the bag, my hopes will be rising ever more.’ (8)Hauptsturmführer Klinter, a company commander in the 3rd SS Division ‘Totenkopf’, reacted with mild surprise to the announcement, and with a casual acceptance typical of many soldiers’ reactions to world political events. ‘The war with Russia will begin early morning at 04.00 hours,’ he declared, adding laconically ‘with Russia?… against Russia.’ He would simply get on with it. ‘It took a while before it had sunk in, and then we thought it through.’ There had been numerous previous examples when the Führer’s political and military perceptions had been proved correct. His fatalistic acceptance was typical of an SS soldier: ‘there was no room then for doubts or thoughts.’ (9)Optimism and quiet resignation generally followed the initial surprise. Benno Zeiser, under training as a driver in a transport unit far from the front, voiced the type of idealistic fervour easily conjured up in the rear.

‘The whole thing should be over in three or four weeks, they said, others were more cautious and gave it two or three months. There was even one who said it would take a whole year, but we laughed him right out. “Why, how long did the Poles take us, and how long to settle France, eh?”’ (10)

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «War Without Garlands»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «War Without Garlands» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «War Without Garlands» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.