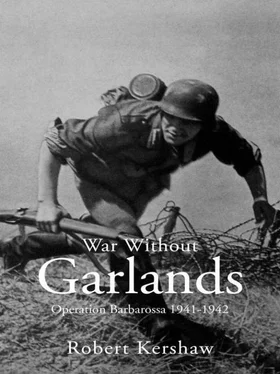

Robert Kershaw - War Without Garlands

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Kershaw - War Without Garlands» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: Hersham, Год выпуска: 2010, ISBN: 2010, Издательство: Ian Allan Publishing, Жанр: military_history, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:War Without Garlands

- Автор:

- Издательство:Ian Allan Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- Город:Hersham

- ISBN:978-07110-3590-1

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

War Without Garlands: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «War Without Garlands»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

War Without Garlands — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «War Without Garlands», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Order and Duty’ and the Führer

‘Order and Duty’ were vital prerequisites demanded of the German soldier. He was familiar with them, because they were established Germanic qualities. The Nazi state harnessed Prussian virtues to its own ends. It was not a question of unthinking, unconditional obedience. They involved self-discipline and self-mastery: willingness to accept the consequences before God and man of one’s own actions, whatever the cost. It was a philosophy that could be, and was, cynically exploited. It started at youth. Henry Metelmann, training as a recruit when the Russian campaign began, commented:

‘Even though my father hated everything connected with the Nazis, I liked it in the Hitler Youth. I thought the uniform was smashing, the dark brown, the black, the swastika and all the shiny leather.’

Roland Kiemig, as a 14-year-old Hitler Youth, reflected, ‘everywhere there was a certain regimentation. You didn’t just walk around uselessly, you marched.’ All this had a certain purpose. Metelmann’s view was that training in the Hitler Youth ‘meant the army was able to train us more speedily’. Therefore, ‘when we were finally let loose on the Panzers, we knew what it was all about.’ (1)Kiemig’s basic training on entering the army subjected him to a rigorous regime that clouded his perception of values. They were replaced with those the army wished him to retain.

‘They kept us on the run, they harassed us, made us run, made us lie down, drove us and tormented us. And we didn’t realise at the time that the purpose was to break us, to make us lose our will so we’d follow orders without asking, “Is this right or wrong?”’ (2)

There was rarely resistance to such a process. Götz Hrt-Reger, a Panzer soldier, explained it was ‘totally normal training in how to be a social being’. They experienced the shock impact any soldier undergoes in the transition from a relatively sheltered civilian life to the rigours of basic military training. ‘Of course,’ remarked Hrt-Reger, ‘if anybody – let’s say – misbehaved, there would naturally be consequences.’ (3)German recruits ran round in circles, frog-jumped, hopped up and down, drilled with full equipment, ran – threw themselves down – got up, and were made to repeat the process. ‘Whenever I see a man in uniform now,’ recalls Panzer soldier Hans Becker, (4)‘I picture him lying on his face waiting for permission to take his nose out of the mud.’ The aim was to wear the recruit down until he responded automatically with no resistance. It worked. Kiemig realised that:

‘This drill – Ach! inhuman at times – was designed to break our pride, to make those young soldiers as malleable as possible so that they would follow any order later on.’ (5)

The decision to invade Russia was not likely, therefore, to generate anything more than superficial discussion, as also their personal moral conduct in that campaign. Leutnant Hubert Becker explained:

‘We didn’t understand the Russian campaign from the beginning, nobody did. But it was an order, and orders must be followed to the best of my ability as a soldier. I am an instrument of the State and I must do my duty.’

Discipline was ingrained. The corruption of values implicit upon acceptance of the Commissar Order was not a subject open for discussion. Many soldiers would agree with Hubert Becker’s opinion voiced after the war. They knew of no alternative.

‘We never felt that the soldier was being misused. We felt as German soldiers, we were serving our country, defending our country, no matter where. Nobody wanted such an action, nobody wanted a campaign, because we knew from our parents and the descriptions of World War 1 what it would entail. They used to say, “If this happens again, it will be fatal.” Then one day I was told I had to march. And opposition to this? That didn’t happen!’ (6)

Faith in the Führer motivated German soldiers poised to invade Russia. The oath of the soldier ‘Ich schwöre …’ was made to Adolf Hitler first, then God and the Fatherland. Henry Metelmann recalled after swearing the oath, ‘we had become real soldiers in every conceivable sense.’ Metelmann’s background and experience was representative of millions of German soldiers waiting on the ‘Barbarossa’ start-line. ‘We were brought up to love our Führer, who was to me like a second God, and when we were told about his great love for us, the German nation, I was often close to tears,’ he wrote. Disillusionment would follow, but in 1941 Hitler was at the height of his powers. Idealism and gratitude for seemingly positive achievements sustained popularity despite setbacks to come. Metelmann recalled with some affection what he felt the Nazis had delivered:

‘Where before we seldom had a decent football to play with, the Hitler Youth provided us with decent sports equipment, and previously out-of-bounds gymnasiums, swimming pools and even stadiums were now open to us. Never in my life had I been on a real holiday – father was much too poor for such an extravagance. Now under Hitler, for very little money I could go to lovely camps in the mountains, by the rivers or near the sea.’ (7)

The Weimar Republic proclaimed in 1918 had borne the burdens of a lost war. It was for many of its citizens simply a way-station for something better. Values such as thrift and hard work had been made irrelevant by inflation. Martin Koller, a Luftwaffe pilot, pointed out: ‘My mother told me, when I was born [in 1923] a bottle of milk cost a billion marks.’ (8)The economy, characterised by high unemployment, low profits and negative balances of payment through the 1920s, appeared to be saved by the advent of the Führer. Bernhard Schmitt, an Alsatian, summed up the feelings of many Germans who voted for Hitler when he said:

‘In 1933–34 Hitler came to power like a knight to the rescue; we thought nothing better could happen to Germany once we saw what he was doing to fight unemployment, corruption and so on.’ (9)

Even Inge Aicher-Scholl, later to lose a brother and sister to the state, said:

‘Hitler, or so we heard, wanted to bring greatness, fortune and prosperity to this Fatherland. He wanted to see that everyone had work and bread, that every German become a free, happy and independent person. We thought that was wonderful, and we wanted to do everything we could to contribute.’ (10)

Even when events turned sour, Hitler’s soldiers continued to believe in him. Otto Kumm, serving in the Waffen SS, admitted: ‘Sure, we had some second thoughts at the end of the western campaign in 1940, when we let the British get away, but these didn’t last long.’ Nobody questioned the higher leadership; indeed, the Führer’s soldiers believed in him. Kumm’s doubts ‘were superficial and didn’t cause us to question Hitler or his genius’. (11)

The German army on the eve of ‘Barbarossa’ was confident in itself and its Führer. Grenadier Georg Buchwald stated: ‘we had done well in France’, (12)an impression shared by Hauptmann Klaus von Bismarck, who opined: ‘We were highly impressed with ourselves – our vitality, our strength and our discipline.’ (13)Victory over France had also changed sentiments back home. Herbert Mittelstadt, a 14-year-old, was astounded to hear his mother refer to ‘our wonderful Führer’ after the French victory. In his view, ‘despite her various and special religious beliefs she must have pondered the matter over a period, that all would turn out positive, and that the war could be won.’ His father had spent three years at the front in World War 1, and had ‘probably always suffered a little with the trauma of the defeat’. (14)

Stefan Thomas, a medic and social democrat, was approached by an old veteran political campaigner who admitted that perhaps they were ‘in the wrong party’. Thomas had cause to reflect: ‘my father had lain three long years in the mud of Champagne before Verdun in World War 1, and now in 1940, one saw France fall apart in a three to four weeks’ Blitzkrieg.’ (15)

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «War Without Garlands»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «War Without Garlands» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «War Without Garlands» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.