Since twin gun mountings required power units which would drastically increase top weight, hand-operated single gun turrets were installed, together with hand-operated torpedo tubes, although a powered hoist was fitted for ammunition. Despite these savings the class was still some 80 tons (81 tonnes) overweight ( Onslow 124 tons – 126 tonnes). [188]

Spending much of their wartime careers on Arctic convoy duty, the class remained in service with the Royal Navy until the mid-1960s.

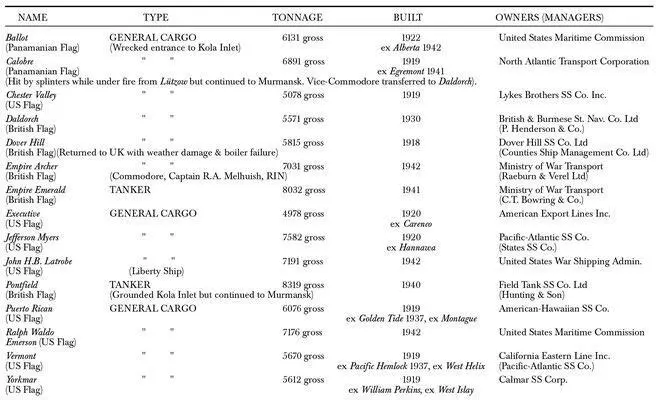

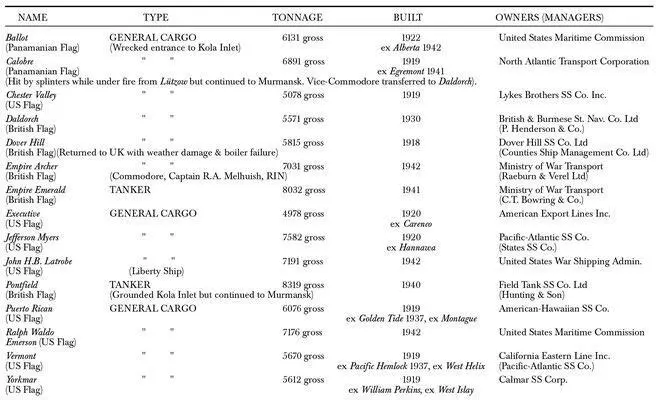

APPENDIX III

OUTLINE DETAILS OF THE MERCHANT SHIPS OF JW51B WITH NOTES ON THE MERCHANT MARINE

In 1938 (the last period for which pre-war figures are available), 192,372 seamen were employed in the British Merchant Marine, of which some 50,700 were foreign, mainly Indian and Chinese. [189]On the outbreak of the Second World War, Britain’s ‘Red Duster’ flew from 3000 deep-sea cargo ships and tankers plus 1000 coastal vessels, amounting to an impressive 21,000,000 gross tons (21,336,000 tonnes), the largest fleet in the world, comprising 33 per cent of total tonnage. On any one day during the war there would be an average of 2500 British vessels at sea to protect, the rapid rate at which they were lost and had to be replaced becoming apparent when the total sunk, 4700 ships (54 per cent of total world merchant ship losses), is compared to the pre-war total of ships in service.

During the war period some 185,000 seamen served on board British merchant ships, of which 40,000 were foreign, mainly Indian and Chinese although seamen were recruited from other countries, notably the West Indies and Aden. Figures vary, dependent upon which source is consulted, but a reasonably accurate figure for British and foreign merchant seamen who lost their lives as a direct result of enemy action would be 33,000, although it is estimated (but not provable), that the casualty rate might be as high as 25 per cent were it to include those who were wounded, shipwrecked, or otherwise affected, and ‘lived permanently damaged lives, still in the shadow of death.’ [190]

In the event of sinking, the chances of being picked up were, in the early years of the war, estimated at 3 to 2 against, although the odds improved as time went on thanks to a number of inventions and improvements in the area of life-saving equipment. Of these, three of the most important were:

• the lifejacket light, first supplied in September/October 1940, compulsory from 6 March 1941

• the manual lifeboat pump, first supplied in July 1941, compulsory from 22 July 1942

• protective clothing, first supplied September 1941, compulsory from 27 July 1942 [191]

Convoy JW51B – Merchant Vessels

Delays would often occur between equipment becoming available and becoming compulsory, as time would be required for supplies to be manufactured in sufficient quantities.

During the early stages of the war, the average working week for a seaman aboard a British ship, before overtime, would be ten hours longer than the all-industry average, with shipboard conditions inferior to those of some comparable nations, notably Norway. Nevertheless the Government promptly instituted a war pensions scheme comparable to that of the Royal Navy, while the Ministry of War Transport, the trade unions and owners came together to improve conditions, notably in the area of mail (very important for crewmen), health, general comfort and conditions of life both in the UK and abroad.

Wages also improved dramatically, although while a single man with nothing to spend his money on during long periods at sea might have seen some benefit from these increases, a married man with a family in Britain to support would have to contend with a dramatic 83 per cent increase in the cost of living between 1939 and 1943. Nevertheless, in the first three and a half years of war a British able seaman’s pay almost trebled:

3 September 1939 – £9. 12s 6d per month.

1 January 1941 – £17. 12s 6d per month.

1 February 1943 – £24. 0s 6d per month. [192]

These amounts include a ‘war risk’ (danger money) payment of £3 rising to £10. In addition to these incremental improvements, paid leave and continuity of employment were introduced for the first time. Foreign seamen were paid less than their British counterparts, a source of understandable friction.

—♦—

Despite the terrible risks involved, there was never a serious shortage of crewmen during the war years, but the same cannot be said of ships for them to sail. By November 1939, the whole of the Belgian fleet had been made available to Britain plus half the Norwegian and Dutch fleets; however, as the German invasion of Europe spread an average of 26 per cent of the Norwegian, Dutch, and Belgian fleets were caught in their home ports and captured. Following the fall of France in June 1940, approximately ½ million tons of French shipping came into British hands, unfortunately matched almost exactly by tonnage of British ships caught in French ports at the same time. Danish shipowners proved to be generally pro-German, and ordered their ships at sea to put into neutral ports, but despite this a number of Danish ships found their way to the UK and operated under British flag, crewed by Danes, for the duration of the war. Greek ships later became an important addition to the fleet.

Formal possession of the ships of the British fleet remained unchanged for the war years, although the Government, through the agency of the Ministry of Shipping (incorporated into the Ministry of War Shipping in May 1941), had, by the summer of 1940, requisitioned all vessels and agreed terms with their owners. [193]This for the most part left crewing, maintenance, and the day-to day running of the ships to the owners, while all decisions as to cargoes and destinations were taken by the Ministry.

By the spring of 1941 a serious shortage of tonnage had manifested itself as a result of war losses. As a consequence, Britain’s annual imports dropped sharply from 42,000,000 tons (42,672,000 tonnes) to 28,500,000 tons (28,956,000 tonnes) – less than had been imported in the dark days of 1917. Britain’s minimum requirement for her civilian population alone amounted to 25,000,000 tons (25,400,000 tonnes) p.a. in addition to which it was estimated that 7–8 tons (7.1–8.1 tonnes) of supplies would be required to support every soldier in Europe when the time for an offensive came – double for the Pacific. To help alleviate the problem, the United States released quantities of old laid up tonnage to Britain on bareboat charter – in which the charterer, in this case the British government, in return for paying a correspondingly low charter rate to the owner, agrees to accept the lion’s share of the risks, and crews and operates the ship as the owner in all but name. The United States further assisted by requisitioning all French, Italian, and Yugoslav ships held in US ports and turning them over to Britain. In 1943 another tonnage crisis was eased when the United States agreed to divert ships from the Pacific to the Atlantic. [194]

That the Allies were able to keep the convoys going at all is due in no small part to the Second World War phenomenon the Liberty ship. This British-designed, 10,800 ton deadweight, [195]11 knot, 3-cylinder steam-engined cargo ship was enthusiastically adopted by the United States Maritime Commission (USMC) which, however, altered the propulsion system from coal- to oil-fired, and to drastically cut building time, changed the hull design from all riveted to all-welded construction. The USMC also instituted a system of prefabrication whereby sections of ships would be constructed at sites all over the country and transported to the shipyards for final assembly. Placing orders in private and government-owned shipyards in the United States, the USMC built 5777 of these amazingly versatile ships between 1939 and 1945, with design configurations varying from the basic general cargo freighter to tankers, hospital ships, floating repair shops and tank transports (‘zipper ships’).

Читать дальше