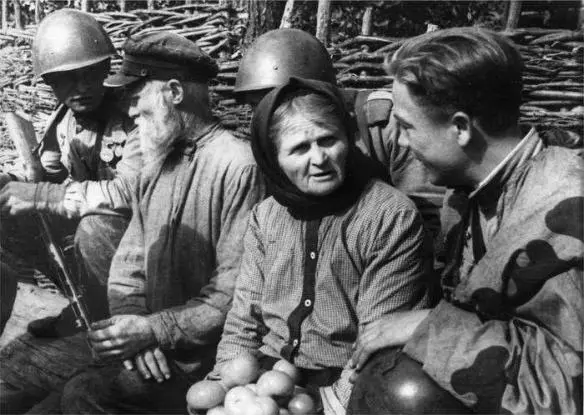

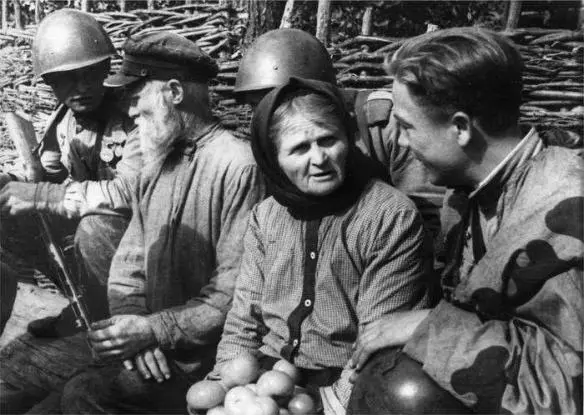

The people who greeted them had seen their fill of violence as well. The German occupation was far worse than Valeriya’s memory describes. Even in the villages, communists and Jews were hanged, women raped and men – such as there were – shipped off to work as slave labour in Hitler’s Reich. The Red Army would free them from all that, but it would also make demands, forcibly evacuating some people from front-line zones, requisitioning precious food and goods, destroying crops and buildings. A survivor would know this, and there are papers in the archive that describe the civil strife, the crime and anger. But Valeriya’s emotion when she saw that tall Russian at the door was not the product of propaganda, even in retrospect. It reflected a hope, an act of faith, the loyalty that Russians felt towards their own, a gratitude that still feeds many veterans’ hearts.

Local people talking to Red Army soldiers, September 1943

Valeriya Mikhailovna never travelled. Her schooling was interrupted by the war and she never managed to complete it, remaining in the province of her birth. The Soviet system under which she spent her adult life did not indulge its citizens with information. An old person now, she has not had the chance to buy and read the glossy magazines that crowd the bookshop windows of the new Russia. She has the same curiosity about outsiders, the same sense of the exotic, as a new soldier might have had in 1943. ‘Tell me about England,’ she asked. I wondered if she wanted to know about Tony Blair, to talk, as many veterans had, about the war in Iraq. ‘Do you have a sea?’ she began. I explained that England was part of a group of islands. We had several seas. ‘But tell me,’ she continued, smiling warmly over her own cups and saucers, ‘is it all right for food in England? Can you get everything you need?’ She wanted to make up a parcel for me with some bread and cucumbers. It is the custom when a journey starts.

Notes – Introduction

1 John Garrard and Carol Garrard (Eds), World War 2 and the Soviet People: Selected Papers from the IV World Congress for Soviet and East European Studies , Houndmills, 1993, pp. 1–2.

2 G. F. Krivosheev, (general editor), Grif sekretnosti snyat: Poteri vooruzhennykh sil SSSR v voinakh, boevykh deistviyakh i voennykh konfliktakh (Moscow, 1993), p. 127.

3 Ibid ., p. 141.

4 It remains impossible to give precise figures for the number of Soviet prisoners of war the Germans captured, not least because so many of the captives died. German figures are still around 2,561,000 for the first five months of the war (Krivosheev, p. 336). The total for the entire war may be higher than 4,500,000. Krivosheev, p. 337; N. D. Kozlov, Obshchestvennye soznanie v gody velikoi otechestvennoi voiny (Saint Petersburg, 1995), p. 87 (gives a figure of over 5 million).

5 Krivosheev, p. 161.

6 John Erickson, ‘The System and the Soldier’ in Paul Addison and Angus Calder, eds, Time to Kill: The Soldier’s Experience of War in the West (London, 1997), p. 236.

7 The figure that commands most support is a ‘demographic loss’ (i.e. excluding returned POWs) of 8,668,400. For a discussion, see Erickson, ‘The System,’ p. 236. Statistics in this war are notoriously unreliable, and it is possible that the true figure is higher by several million.

8 See Chapter 4, p. 109, and Chapter 5, p. 145.

9 Antony Beevor, Stalingrad (London, 1998), p. 30.

10 Krivosheev (p. 92) gives a figure of 34,476,700 for the women and men who ‘donned military uniform during the war’.

11 The classic American accounts include S. L. A. Marshall, Men Against Fire: The Problem of Battle Command in Future Wars (New York, 1947) and Samuel A. Stouffer et al., The American Soldier (2 vols, Princeton, 1949).

12 Among the first post-war studies was E. Shils and M. Janowitz,’ Cohesion and disintegration in the Wehrmacht in World War Two’, Public Opinion Quarterly , 12:2, 1948. The Wehrmacht’s performance is examined comparatively in Martin van Creveld, Fighting Power: German and US Army Performance, 1939–1945 (London and Melbourne, 1983). A more recent, but classic, account is Omer Bartov, Hitler’s Army: Soldiers, Nazis and the Third Reich (New York, 1992).

13 Cited in Catherine Merridale, Night of Stone: Death and Memory in Russia (London, 2000), p. 218. For a moving account of the famine, see R. Conquest, Harvest of Sorrow (Oxford, 1986).

14 The story of this violence is explored in my Night of Stone .

15 Richard Overy, Russia’s War (London, 1997), pp. xviii–xix.

16 For a more detailed commentary on wartime poetry, see K. Hodgson, Written with the Bayonet: Soviet Russian Poetry of World War Two (Liverpool, 1996).

17 Grossman himself was condemned when his great war novel, Life and Fate , was judged to be ‘devoid of human feelings, friendship, love and care for children’. The banning of Life and Fate , including the references that his critics made to the needs of veterans, is discussed in Night of Stone , pp. 319–20.

18 The phrase is used as the title for one of the tales in Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried (London, 1991).

19 Among the most energetic exponents of this is Elena Senyavskaya, of the Academy of Sciences in Moscow, whose generous help and warm encouragement of colleagues, including me, has fostered an entire school of new research. See, for example, her Psikhologiya voiny v XX veke: istoricheskii opyt rossii (Moscow, 1999).

20 The most treasured series is Russkii Arkhiv’s Velikaya Otechestvennaya , a multi-volume set of reprints of wartime laws, regulations and military orders published in Moscow since the 1990s. Its striking scarlet bindings came to seem like a trophy of true veteran status, at least in the capital.

21 Some, such as the results of the 2000–1 competition, have been published. See Rossiya-XX vek, sbornik rabot pobeditelei (Moscow, 2002).

22 Oksana Bocharova and Mariya Belova, a social scientist and an ethnographer respectively, at different times also carried out interviews alone, as well as staying in touch with veterans after the interviews. In several cases, the result was a correspondence that continued for months.

23 Cited in John Ellis, The Sharp End: The Fighting Man in World War II (London, 1980), p. 109.

24 For a discussion, see Nina Tumarkin, The Living and the Dead: The Rise and Fall of the Cult of World War II in Russia (New York, 1994).

25 The surviving fruits of those interrogations and enquiries, which I was able to consult thanks to the help of German colleagues, are archived in the military section of the Bundesarchiv in Freiburg.

26 Donald S. Detwiler et al . (Eds), World War II German Military Studies (24 vols, New York and London, 1979), vol. 19, document D-036.

27 Russian Combat Methods in World War II , Department of the Army pamphlet no. 20–230, 1950. Reprinted in Detwiler, vol. 18.

28 The observation, by Lt-Gen Martel, applied to Soviet troops in 1936. Cited in Raymond L. Garthoff, How Russia Makes War (London, 1954), p. 226; see also ibid ., p. 224.

29 Some people used this designation to answer the question on ‘nationality’ in the census of 1937. At the other extreme were individuals who answered ‘anything but Soviet’. See Catherine Merridale, ‘The USSR Population Census of 1937 and the Limits of Stalinist Rule,’ Historical Journal , 39:1, March 1996, pp. 225–40.

Читать дальше