The next diary entry was October 20: “First snow. Pretty cold.” With it began my first winter in Russia.

Winter was early this year, the guard said, the earliest in seventy years, meaning it would be long and hard.

Our radiator was the old-fashioned type. When the wind was blowing from the west, or opposite, side of the building, the cell was nice and warm. When it came from the east, however, our teeth chattered.

When the temperature dropped below freezing, we were allowed to divide our walk time, so as to have one hour in the morning, the other in the afternoon. Even then we rarely wanted to stay out the full hour. We would walk steadily, stopping only to feed the pigeons.

As the days grew shorter, daylight did not come until eight in the morning, and getting up at six became more difficult. I no longer looked forward to the morning trip to the bathroom. Now, with the window open, the temperature inside was the same as out. It was something to be endured.

Winter brought some advantages. The milk didn’t spoil. And the dead-air space between the two windows became a freezer where we could store what meat Zigurd’s parents sent, permitting us to ration it out for a longer period.

Diary, October 23, 1960: “Saw a movie about a poet and artist in prerevolutionary days. Good, though I didn’t understand it enough to enjoy it thoroughly.”

October 29: “Saw another movie about construction of a railroad bridge in Siberia. Fair.”

The diary entries were brief, for two reasons. There was very little to write about, and it was so cold in the cell now that we had to wear gloves.

Letter to Barbara, October 31: “Winter has definitely set in here. It has snowed almost every day since the twentieth. The temperature has been freezing or below for about three weeks now….

“I suppose you have read about the American tourist who was sentenced to seven years for spying and who was released when he appealed to the Presidium. I heard about it on the Moscow News and was very surprised. He was convicted under the same article as I was, but then, his case was much different from mine.

“I am tempted to write an appeal, although I am sure it would do no good. One doesn’t know until one tries, though. Many things that have happened here have surprised me. Last May I didn’t think I would be alive in October, but here I am. I guess I should be satisfied, but I still hope for some miracle to happen.”

It was an up-and-down cycle. There were all-right days, and bad ones.

Diary, November 1: “Usual day of prison life. Have now been in prison for six months. I am sure I will never stay for ten years. Will do something drastic first.”

November 4: “People from Moscow KGB visited me today.”

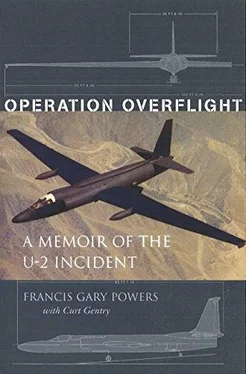

The visit, which came as a surprise, was my first real interrogation since the trial. Obviously aeronautical experts had been studying the remains of the U-2, since all questions concerned the aircraft. Handing me photographs, they would ask: Why does the drive shaft in this electrical motor turn this way instead of that? Why do the flaps move up as well as down? There was nothing in this to fall into the realm of security or to give them any sort of technical advantage, yet I had resisted their questioning for so long that it was an ingrained habit. I answered all the obvious ones, replying to the others that when a pilot flips a switch he knows only that certain things are supposed to happen; he doesn’t necessarily know the engineering sequence involved.

Early in October, deciding to follow Zigurd’s example and keep a journal, I had ordered a bound notebook from Moscow. It finally arrived, and on November 4 I made my first entry.

The purpose of my journal, I decided, would be to put down everything I could remember about the May 1 flight and events following. If I didn’t do this, I’d probably forget many details, and there were some in which, I was sure, the CIA would be most interested. Like the diary, however, the journal posed two problems: when I was released, I might not be allowed to take it with me: and, in the interim, my jailers might read or copy it while we were outside the cell. Therefore I would have to continue to maintain all the fictions: this had been my first overflight; I had learned I was to make it only a few hours before takeoff; and so on. When it came to touchy matters, I decided to use a memory code, words or phrases to serve as reminders of things I didn’t wish to have read. Even should they keep both the journal and the diary, the two would have served one positive function—giving me something to do. But since I did want to keep them, I took out some insurance. Here and there I’d add a phrase such as “No brainwashing here… ” or “Have never seen a prisoner mistreated…,” the kind of thing they would be anxious to have publicized. I didn’t know if it would help, but it wouldn’t hurt.

Before leaving Moscow, Barbara had been unable to find some of the winter clothing I needed. One of the KGB officials had told her that they wouldn’t hold too strictly to the one-package rule; she could send the remainder upon her return to the United States. On November 5 the package arrived, containing some much-needed winter long Johns, an extra pair of shoes, a puzzle and a bridge game, and various other items. Its value was declared at sixty-seven dollars, the postage $49.54, and the customs duty twelve hundred rubles. There wasn’t anything I needed that much, I decided.

Except possibly a letter. Although I searched the package, there wasn’t one. It had been nearly a month since I had received her last.

Representatives of the KGB came about every two weeks. I told them bluntly, “I’m not getting all my mail. The letters from my wife aren’t coming through. You must be stopping them.”

“No,” they insisted, “we aren’t. But we’ll check and see.”

They seemed very disturbed that I would even think they would do such a thing.

During the trial I had stated that I felt no animosity toward the Russian people. This was true. Although I had no fondness for my interrogators at Lubyanka, and I harbored only contempt for the trial team of Rudenko-Grinev, the majority of the people I had met in Russia, from the farmers who captured me in the field to my guards at Vladimir, were friendly and without malice. Ordinary people, they were as curious about me as I about them. Apparently each of us had been led to believe the other monstrous; the discovery that this wasn’t true was a pleasant surprise. A few of the guards had been surly, but they were surly to everyone. By contrast, the Little Major seemed jolly whatever the occasion.

I could honestly say that while an uninvited house guest of the Russians, I had never met anyone I really hated.

On November 6 I met the exception.

That day Zigurd and I were taken to the theater to watch a concert put on by some of the work-camp prisoners. There was a comedy skit—the comedian easily recognizable by his long nose; several of the prisoners were quite talented musicians; and one, a large dark man known as “Gypsy,” did fabulous cossack dances.

While we were sitting on the bench in the projection room, the prison commander walked in. I glanced at him briefly—I had seen him only once previously, on the day of my arrival—then returned my attention to the show.

Angrily, with Zigurd acting as a reluctant interpreter, he demanded that I stand at attention.

All prisoners were required to stand in the presence of the prison commander, he bellowed. No one had told me this. When someone came into the cell, we stood automatically, out of simple politeness, but I’d never given it any thought.

For a good ten minutes he cursed me, and the United States, with the vilest epithets he could muster, only a portion of which Zigurd repeated.

Читать дальше