Zigurd was already asleep. As usual, I was restlessly tossing and turning, when I caught the first acrid whiff.

“Zigurd” I cried; “something’s on fire!”

Whatever it was, it wasn’t in our cell. As the smoke smell grew stronger, we could hear running feet; that sound was soon drowned out by prisoners in other cells yelling or banging on their doors.

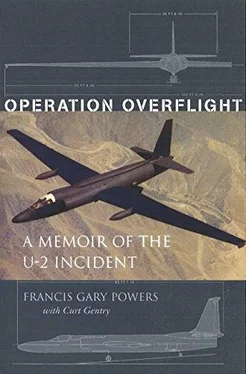

I had never known pure panic before. Not even when I thought I was trapped in the falling U-2 matched what I felt then. The building was old, the floors wood, we were locked in with no way to get out.

After a while the acrid smell diminished, and finally the cellblock became quiet again.

The next morning, although sure he already knew the answer, Zigurd asked the guard what had happened.

One of the prisoners had gone mad and set his mattress on fire.

Even though I was not allowed American newspapers or news magazines, we could obtain, fairly regularly, Pravda and the French Communist newspaper L’Humanité, and, occasionally, the American Worker and the British Daily Worker.

Of the last two, I preferred the British version. Though it had just as much propaganda, it also contained straight news dispatches from Reuters.

As for the other two papers, they played special roles in our lives.

Although Russian cigarettes could be purchased from the commissary, and I obtained American cigarettes in my embassy package, once a week each prisoner was issued a few ounces of coarse tobacco, made from ground-up tobacco stalks, for roll-your-owns.

There was a saying in the prison: Pravda best for cigarette paper, L’Humanité for toilet tissue.

Communist propaganda does have its uses.

On September 21 I was told I would be allowed to write four letters per month. I decided, initially, to write two to Barbara, one to my parents, then, on different months, to alternate the remaining one among my sisters.

Unlike at Lubyanka, there was no attempt to dictate contents, nor were the letters edited, then rewritten. They were read, however, and we left the envelopes unsealed for that purpose.

As yet I hadn’t received any mail from home. Though the move from Moscow had probably delayed it, it still concerned me. Zigurd suggested that in the future I do what he did. Work up an arrangement with my correspondents to number our letters. That way we could tell if any were missing.

I tried to make my letters as cheery as possible. This took some imagination, and even then didn’t always come off. For example, in my first letter I noted, “Don’t worry about me. Where I am there is very little that can happen to me. I am safer here than in an airplane. Think of it that way.”

I neglected to add that, given a choice, I’d pick the sky.

Airplanes were very much on my mind, particularly after I had discovered that jets would occasionally pass overhead. Apparently we were near a letdown pattern. Several times, on our walks, I recognized MIG 17s and 15s.

Because to me flying had always been a form of freedom, the sound and sight of those MIGs filled me with special longing.

Although there was no evidence that our cell was bugged, we automatically presumed this to be the case, and by unspoken agreement saved certain topics of conversation for our walks. Escape was one.

We didn’t admit it was impossible. To do so would have been to surrender one of our few hopes. But, considered realistically, we had to face the fact that our prospects were less than good.

Sawing bars and dropping two stories to the ground was out. We couldn’t even reach the bars, without first breaking several windows.

The guards inside the prison had no guns. But those in the towers did. No prisoner ever crossed the yard alone. Even service personnel—cooks and others—were escorted. Seeing a prisoner without escort, guards were under orders to shoot.

I tried to remember some notable POW escapes during World War II. Most had involved digging tunnels. We weren’t near any ground. The walk area was asphalt. And we were watched every minute.

During the war POWs were usually housed in barracks, in large groups. Thus they could plan, assign duties, establish cover, create diversions. Except for shower day, when there were guards present, we had no contact whatsoever with other prisoners. There was never a time, not even in the toilet, that we weren’t subject to surveillance.

On October 11 received three letters, two from my parents, one from my sister Jessie. The dates—September 13, 17, 19—indicated a delay of twelve to eighteen days.

The first letter from Barbara did not arrive until a week later. It was dated September 10, and had taken twenty-seven days.

She had answered two of mine with one of hers. Unless some letters were missing, this was the first time she had written since the trial, and that bothered me. Her news wasn’t good. Neither Khrushchev nor Brezhnev had acknowledged receiving the appeals.

Yet just receiving mail made the day an occasion. And to top it off, that afternoon I saw my first movie.

The theater was located in the work-camp barracks; about forty prisoners were already in the small auditorium, seated on wooden benches, when we arrived. We weren’t allowed to join them. My cellmate and I, plus a guard, shared a bench in the projection room, watching the movie through a small glass window. Here, as elsewhere, the “politicals” were strictly segregated, not only from other prisoners but also from each other. No more than one or two attended each showing.

Between reels the lights would come on, and the work-camp inmates would turn around in their seats to stare up at us in frank curiosity. I was equally curious about them.

We were forbidden to talk to the projectionists, who were also prisoners. However, you don’t need words to convey a feeling of mutual sympathy.

The movie was about deep-sea diving. Zigurd translated enough for me to follow the plot. It wasn’t particularly good, but the change was most welcome.

Sometimes, Zigurd told me, there would be a movie almost every week. At other times, months would pass before the prison received a print. Too, it was a privilege revocable at any time, on whim of the authorities. During one period the Soviets had attempted to make Vladimir a “showcase prison,” even allowing TV. That phase had quickly passed. Now it was like any other, a place apart from the main current of life; yet, not quite. There were political commissars, to make sure prisoners were indoctrinated in each change of party line. And whenever there was a food shortage in the Soviet Union, prisoners were among the first to feel it.

On October 13 I received some good news: although I could write only four letters each month, I could receive as many as were sent me. I wrote Barbara to this effect, adding something else that had been on my mind: “This is grasping at straws, I know, but have you heard anything at all about the possibility of an exchange of prisoners? Maybe you could get the lawyers who accompanied you to Moscow to check into this and maybe accomplish something in this direction. If it isn’t pushed, it will probably be forgotten. I realize there are probably more important people they would rather exchange for; but I can hope.”

By the lawyers, I of course meant the CIA.

Diary, October 15: “Saw my second movie—about a quarrel on a collective farm. Not real good.”

After that I’d rarely have to ask Zigurd to explain the plot. All too often it was the same one: boy tractor driver meets girl tractor driver; they fall in love and drive tractors together.

Occasionally the singing was good. The acting was something else.

Читать дальше