For their advice and their support, huge thanks to my family and friends, among them Ben Summerscale, Juliet Summerscale, Valerie Summerscale, Peter Summerscale, Robert Randall, Daniel Nogues, Victoria Lane, Toby Clements, Sinclair McKay, Lorna Bradbury, Alex Clark, Will Cohu, Ruth Metzstein, Stephen O'Connell, Keith Wilson and Miranda Fricker. In the early stages of my research, I was sent to excellent sources by Sarah Wise, Rebecca Gowers, Robert Douglas-Fairhurst and Kathryn Hughes. Towards the end, I had wonderful readers in Anthea Trodd and Peter Parker. My thanks also to PD James for her observations on this case and to former Detective-Inspector Douglas Campbell for his comments about detective work in general.

For putting so much into publishing the book, thank you to Alexandra Pringle, Mary Morris, Kate Tindal-Robertson, Meike Boening, Kathleen Farrar, Polly Napper, Kate Bland, David Mann, Phillip Beresford, Robert Lacey, and the rest of the brilliant people at Bloomsbury. Thank you to my terrific editors at Walker & Co, George Gibson and Michele Amundsen, and to the other publishers who have shown faith in the book, including Andreu Jaume of Lumen S.A. in Barcelona, Dorothee Grisebach of Berlin Verlag, Dominique Bourgois of Christian Bourgois Editeur in Paris, Andrea Canobbio of Giulio Einaudi Editore in Turin, and Nikolai Naumenko of AST in Moscow. I am grateful also to Angus Cargill and Charlotte Greig for their early interest and encouragement. My thanks to the excellent Laurence Laluyaux, Stephen Edwards and Hannah Westland of Rogers, Coleridge & White Ltd, to Julia Kreitman of The Agency, and to Melanie Jackson in New York. Special thanks to David Miller, my friend and agent, for always seeming to understand better than I did what it was that I was trying to do. His contribution to this book is immeasurable. My son, Sam, has already been rewarded (with a trip to Legoland) for being patient while I worked, but I'd like to thank him here for being altogether fantastic.

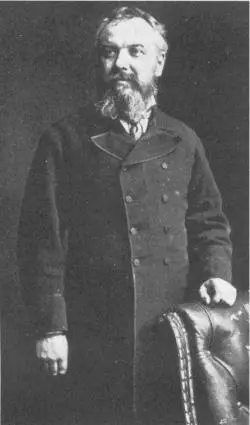

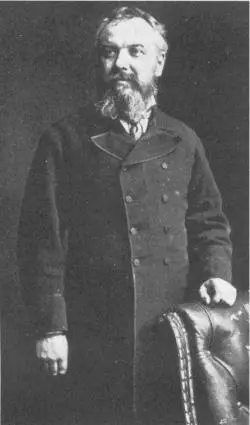

Samuel Kent, circa 1863

The second Mrs Kent, circa 1863

Sketch of Elizabeth Gough in 1860

Constance Kent, circa 1858

Edward Kent, early 1850s

Mary Ann Windus in 1828, a year before she became the first Mrs Kent

Road Hill House, front view

Road Hill House, back view, with the drawing-room windows to the right

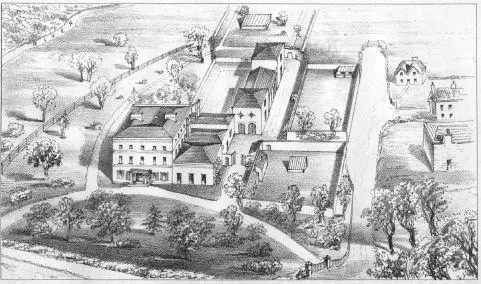

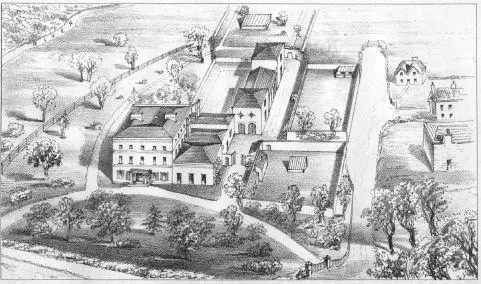

Engraving of Road Hill House in 1860, bird's-eye view

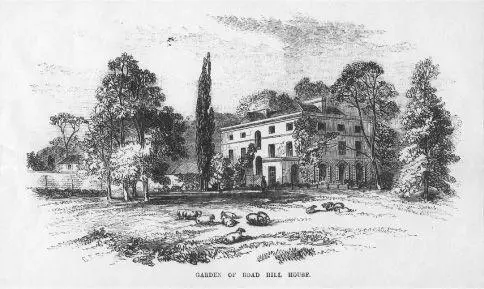

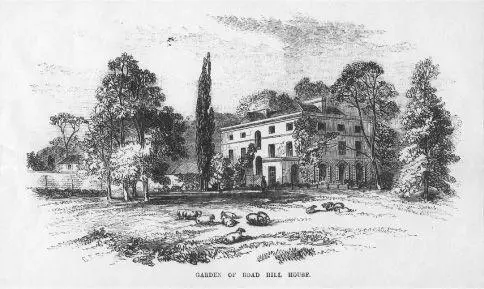

Engraving of Road Hill House in 1860, back view

Adolphus 'Dolly' Williamson, police detective, in the 1880s

Richard Mayne, Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, in the 1840s

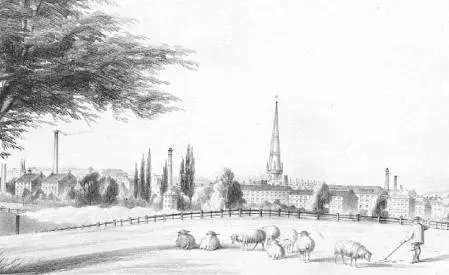

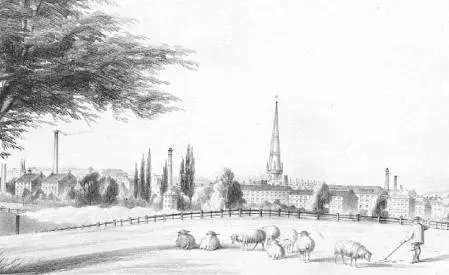

A view of Trowbridge, Wiltshire, in the mid-nineteenth century

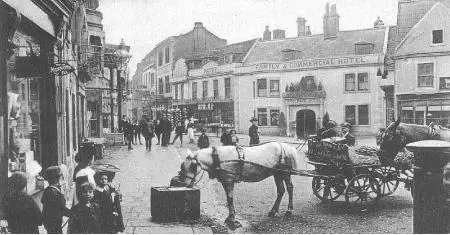

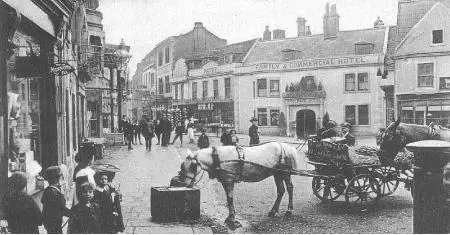

The centre of Trowbridge in the late nineteenth century

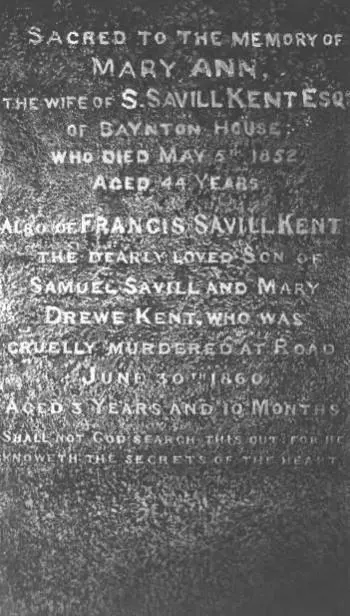

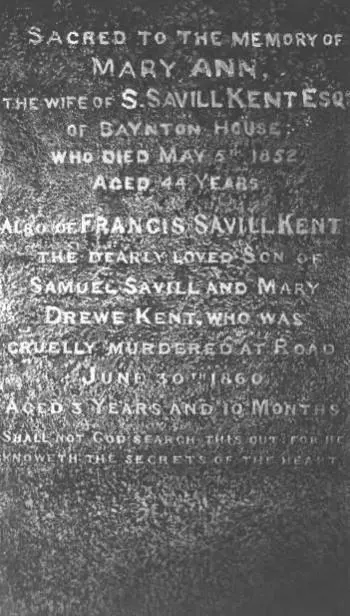

Gravestone in East Coulston churchyard, Wiltshire

* That month, according to the News of the World , a worker at a crinoline steel factory in Sheffield was killed by her crinoline when it caught in the revolving shaft of a machine and pulled her to her death.

* Though his name did not appear on the census of 1861, there are indications that Whicher was living in this house by 1860. In a police circular of 1858 he asked fellow officers to inform him, at Scotland Yard, if they saw a twenty-four-year-old gentleman who had gone missing, 'mind supposed affected'; two weeks afterwards a private advertisement appeared in The Times requesting news of this same young man, with his 'rather pale full face', and offering a PS10 reward - it was presumably placed by Whicher, but it asked that information be passed to 'Mr Wilson' of 31 Holywell Street. The pseudonym concealed the fact that the police were looking for the wan gentleman. 'The tricks of detective police officers are infinite,' observes the narrator of The Female Detective. 'I am afraid many a kindly-disposed advertisement hides the hoof of detection.' A year later, in 1859, the Commissioner's office put out a request for information about a white, wolf-breed dog that had gone missing from 31 Holywell Street. A lost dog was not usually a matter for Scotland Yard - maybe the white wolfhound belonged to Whicher's landlady (Charlotte Piper, a widow of forty-eight with a private income) or to the detective himself.

* In the next decade Road Hill House was renamed Langham House (after the neighbouring farm). By 1871 the head of the house-hold was Sarah Ann Turberwell, a widow of sixty-six, who employed six staff: a butler, a lady's maid, a housekeeper, a housemaid, a kitchen maid and a footman. In the twentieth century the county boundaries were altered, so that the house now falls within Somerset, like the rest of the village, and the name of the village itself was changed, from Road to Rode.

* To demonstrate the weird logic of homicidal monomania, Stapleton recounted a horrible story about a mild-mannered young man who was so obsessed with windmills that he would gaze at them for days on end. In 1843 friends tried to distract him from his fixation by moving him to an area with no mills. There the windmill man lured a boy into a wood, then killed and mutilated him. His motive, he explained, was the hope that as punishment he would be taken to a place where there just might be a mill.

* James Willes separated from his wife in 1865 and moved to a house on the banks of the Colne, in Essex. Over the next few years, according to the Dictionary of National Biography , he walked his three dogs by the river and fed the trout. Though he had been a keen fisherman in his youth, he developed such a fondness for the fish that he banned the sport in his waters. In 1872, on becoming sleepless, forgetful and depressed, he shot himself in the heart with a revolver.

Читать дальше