After this row Dyemchuk reported fearfully to his master that some other cosmonauts and senior staff in the Star City compound had asked to use Gagarin’s official car, and Dyemchuk, as a humble driver, had not been able to refuse them. ‘He hit the car with his fist and said, “We have one commander here, and he’s the only person who can order the car!” Apart from him, no one could reserve it. He showed his emotions and a small dent was left in the bonnet.’ Dyemchuk is convinced that this outburst was entirely out of character for Gagarin, the result of stress rather than vanity.

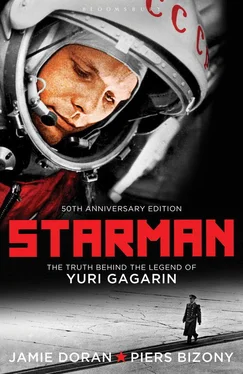

Yaroslav Golovanov says, ‘Around this time you heard other cosmonauts saying, “So what, about Gagarin? He flew once around the earth, and all he had to do was watch over Vostok’s automatic systems.” Well, that’s not right, because when he flew, the whole business [of space flight] was starting from scratch, and everything he did was extremely important and brave, because nobody knew what might happen. They didn’t even know if a man could swallow properly in space, or endure the lack of gravity. It’s completely wrong to reproach Gagarin.’

Almost certainly these critics, muttering under their breath, were not from the first group of twenty, but from the new intake training for Soyuz. Not only had Korolev’s death deprived Gagarin of a dear friend and mentor, it had also taken away his most important political protector in the space community, just as Khrushchev’s fall from power had left him defenceless against jealous generals in the Kremlin. The First Cosmonaut had to fight unusually hard to maintain his position in the cosmonaut hierarchy, and the strain was wearing away at his old easy-going nature. Meanwhile OKB-1 was becoming a weaker bureau under the leadership of Vasily Mishin, who could not defend himself as effectively as Korolev against interference from the Kremlin, or from the vicious competition of rival aerospace bureaux anxious to increase their own profile in space.

Suddenly NASA’s gigantic moon programme came to a halt. On January 27, 1967 Gus Grissom and his crewmates, Ed White and Roger Chaffee, clambered into the first flight-ready Apollo, atop a half-sized version of the Saturn rocket. This was supposedly a routine check-out procedure, during which they would run a simulated countdown with all systems running and bring the ship to the very last second before take-off, without actually igniting Saturn’s engines. Morale around the pad was poor, even before the test began, because the new capsule had not come up to expectations. The detail work on the electrical and communications systems was inadequate, prompting the astronauts to stick a mouldy lemon on top of the capsule’s duplicate simulator to show their contempt for the overall design. When Chaffee climbed through the hatch of the flight vehicle to start the test, he complained that the interior smelled of sour milk. The consensus was that the balky environmental control hardware was generating fumes. Then the radio system glitched. Furious, Grissom shouted, ‘How the hell are we supposed to communicate with mission control from space when we can’t even talk to them on the ground!’ The mood around the Kennedy launch complex was distinctly strained as the technicians locked Apollo’s heavy hatch into place, sealing the crew inside.

Five hours into the test, Grissom’s garbled voice on the crackling radio link said, ‘We’ve got a fire in the capsule.’ A few seconds later, another voice (possibly White’s) was more urgent. ‘Hey, we’re burning up in here!’ There was a scream of pain, then just a hiss of static as the radio went dead. Suddenly the side of the capsule split open. There was a horrifying ‘whoosh!’ as the top of the launch tower was engulfed in thick, acrid smoke and flames. The pad crew, high atop the gantry, tried desperately to get the astronauts out, but the smoke was impenetrable and the heat quite overpowering. It took four minutes to open Apollo’s hatch, by which time all three astronauts were dead. [2] The Apollo I fire exposed some scandalous business relationships and incompetencies associated with the NASA moon project. For an eye-opening account, see Young, Journey to Tranquillity , pp. 212–48.

The tragedy was reminiscent of Valentin Bondarenko’s death in the isolation chamber back in 1960, but NASA could not draw any lessons from that because of the obsessive secrecy that always surrounded the Soviet space effort.

NASA entered a two-year hiatus, a period of self-doubt, its technical and political reputation severely tarnished by the deaths. The Soviet cosmonauts grieved for their US counterparts, and were permitted to send official expressions of condolence to the dead men’s families, even as Leonid Brezhnev and Vasily Mishin speculated about the window of opportunity that had arisen for the Soviet space effort to take advantage of NASA’s enforced slow-down.

The Soviets’ gigantic N-1 lunar superbooster was running badly behind schedule, and even the demoralized Americans knew that it did not present a serious threat. According to a National Intelligence Estimate document of March 2, 1967, their appraisal of the N-1 was that:

Several factors militate against the Soviets being able to compete with the Apollo timetable… Their lunar launch vehicle will probably not be ready for test until mid-1968, and even then we would expect to see a series of unmanned tests lasting about a year to qualify the system before a lunar landing might be attempted. In the meantime they still have to test rendezvous and docking techniques. [3] Archives of Dr John Logsdon, Space Policy Institute, George Washington University, Washington, DC, National Intelligence Estimate Number 11-1-67, March 2, 1967, ‘The Soviet Space Programme’, p. 18.

The landing and return of a man on the moon seemed very far off yet for Mishin and his beleaguered team at OKB-1; but a much simpler circumlunar flight, Jules Verne-style, might be achievable without the need for the colossal and as yet unflown N-1 booster. Korolev’s old rivals in the aerospace community, Glushko and Chelomei, were developing a rocket called Proton, which was larger and more powerful than the R-7 but not quite powerful enough to carry a lunar landing module as well as a crew return capsule. Mishin faced a difficult choice: if he opted for the circumlunar flight aboard Chelomei’s Proton, he would have to sacrifice some development work on the N-1 and the bug-like landing craft; but if he could achieve a fairly basic ‘once-around-the-moon’ flight while NASA was still preoccupied with recovering from the Apollo fire, any subsequent walkabout on the lunar surface by American astronauts would come across as yet another second-best. With this tantalizing prize in mind, work on the new Soyuz capsule was accelerated, while the N-1 was allowed to fall further behind and Korolev’s old enemies dug their claws deeper into OKB-1.

The cosmonaut team was affected by all these complications. Leonov began training a squad for a touchdown mission with the N-1, which would include the use of the tiny one-man lunar landing pod, while another team of astronauts was prepared for circumlunar flights aboard the Proton, using an elongated Soyuz variant known as a ‘Zond’. Meanwhile, yet another group, including Gagarin, was training for the first basic earth-orbital test of the Soyuz mated to a standard R-7. In contrast to the overall NASA effort, with Apollo as its privileged centrepiece, the Soviet lunar programmes were divided, confused and contradictory, especially in the absence of Korolev’s managerial discipline.

By the spring of 1967, development of the Soyuz was moving towards that crucial first flight. On April 22 the Soviet propaganda departments felt confident enough to let slip some rumours to the international press agency, UPI. ‘The up-coming mission will include the most spectacular Soviet space venture in history – an attempted in-flight hook-up between two ships and a transfer of crews.’ But some doubts seemed to be preying on Nikolai Kamanin’s mind. His diary more or less implies political pressure to push the Soyuz launch schedule forward:

Читать дальше