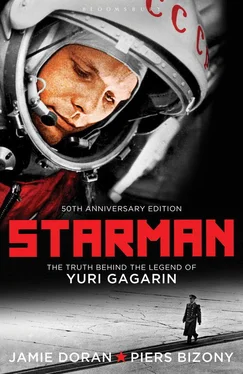

Leonov puts this (and other similar incidents) down to Gagarin’s perceptions of the earth from space. ‘After his flight he was always saying how special the world is, and how we had to be very careful not to break it.’ This is a common enough truism by modern standards, taught to all of us in school, but what must it have been like for the very first man in space to discover it for himself? In April 1961 Gagarin was the only human being among three billion who had actually seen the world as a tiny blue ball drifting through the infinite cosmic darkness.

So the tree-cutter lost his job at Gagarin’s specific request, but more often he was inclined to help his petitioners by appealing to higher authorities. ‘You could hardly find a single man who wouldn’t assist him if he asked for it. Who could refuse him?’ says Yegupov.

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev could.

In his first months in office, Brezhnev was preoccupied with achieving dominance over his co-conspirator Alexei Kosygin. Brezhnev’s attitude towards Korolev was similar to Khruschev’s: an insistence on orbital ‘firsts’, accompanied by a hazy lack of interest in the exact technical details. However, the scheduled mission of Voskhod II did interest Brezhnev, because it promised a major new triumph: the first spacewalk, enabled by a flexible airlock attached to the re-entry ball’s flank. Korolev was just as keen to try out this new concept. In 1962 he prepared Leonov, who was one of the prime candidates for the first walk, with a suitable pep-talk. ‘He told me that any sailor has to learn to swim, and each cosmonaut has to know how to swim and do construction work outside his vehicle.’

On February 23, 1965, Korolev launched an unmanned test vehicle with the new airlock attached. The mission ended badly when the capsule broke up during re-entry, as a result of poor command signalling from the ground. A few days later, an air-drop of the capsule from a plane also failed because the parachute did not open. Oleg Ivanovsky remembers Korolev saying in disgust, ‘I’m sick of flying under rags.’ He hated parachutes and always wished that he could design a rigid rotor system, or some other aerodynamic device to replace them. Perhaps it was a mercy that he never lived to see a much more terrible parachute failure in April 1967: a failure that might easily have claimed the life of Yuri Gagarin…

The Voskhod II mission took off on March 18, 1965 with wonderful timing, ahead of NASA’s first Gemini mission by just six days. This time there were only two crewmen in the cabin, to make room for their bulky spacesuits. Pavel Belyayev remained inside, while his co-pilot Alexei Leonov squeezed into the flexible airlock and pushed himself out of the capsule. For ten minutes he enjoyed the exhilarating sensation of spacewalking, and then began to pull himself back into the ship – only to discover that his suit, at full pressure, had ballooned outwards, so that he could no longer fit into the airlock. Extremely exhausted by his efforts, Leonov had to let some of the air out of his suit to collapse it, so that he could squeeze back aboard.

Then, prior to coming home the next day, Belyayev saw that the ship’s attitude was incorrect for the braking burn, and he shut down the automatic guidance systems before they could make matters any worse. With help from Korolev and ground control, he and Leonov had to ignite the braking motors manually on the next orbit, displacing their eventual landing site by 2,000 kilometres. The capsule descended onto snow-covered wilderness near Perm, alongside the very northernmost reaches of the Volga. It smashed into a dense cluster of fir trees and was wedged several metres off the ground between two sturdy trunks. Meanwhile the recovery teams were 2,000 kilometres away, in the zone where they had expected the capsule to come down. The cosmonauts had to spend a restless, frozen night waiting to be picked up. They pushed open the capsule’s hatch but dared not climb down from their precarious perch, because a pack of wolves was howling somewhere very nearby in the darkness. [5] A detailed account of the Voskhod II mission can be found in Harvey, The New Russian Space Programme , pp. 82–8. See also: Newkirk, Almanac of Soviet Manned Spaceflight , pp. 35–7.

These difficulties were not mentioned in the Soviet press reports, and the mission was a great propaganda triumph all around the world, particularly after Yuri Mazzhorin had responded to a stern phone call from Alexei Kosygin’s office. ‘They said that not a single word about the landing in Perm should appear in the media. I had

no idea what that region looked like, but I had to go to all the television stations and make sure you couldn’t identify Perm in any of their news footage.’ Subterfuge aside, the fact remains that Alexei Leonov walked in space well ahead of his American rivals. The London Evening Standard ran an article about the US astronauts Young and Grissom, gearing up for the first Gemini shot, with the headline ‘follow that cab!’, while The Times described Leonov’s adventure as ‘a fantastic moment in history’. Once again NASA had been trumped. Leonov’s spacewalking rival, Ed White, did not get his own chance to catch up until the second Gemini mission on June 3, nearly three months after Voskhod II’s flight.

An accomplished artist, Leonov set about designing a commemorative postage stamp showing his spacewalk, and spent hours happily chatting with Gagarin about the differences each man had observed in the curvature of the earth. ‘My view was much steeper, much rounder than Gagarin had reported, and it worried me, but then we realized that Voskhod’s maximum orbital altitude was 500 kilometres, and Vostok’s 250 kilometres, so I was much higher. You see, everything has a sensible physical explanation.’ It was the infernal rules of secrecy that made no sense. Leonov’s innocent stamp designs had to be vetted by the KGB propaganda experts. ‘Everything was so secret – they were all civil servants, you see. I drew a completely different spacecraft that wasn’t anything like [the one that had really flown] and then they were satisfied.’

In the wake of this more-or-less successful mission, Voskhod III was scheduled to coincide with the Party Congress of March 1966. Cosmonauts Georgi Shonin and Boris Volynov began training for an ambitious rendezvous with an unmanned target vehicle. Even the journalist Yaroslav Golovanov was recruited for forthcoming Voskhod missions, along with two other writers, after Korolev had expressed frustration at the cosmonauts’ rather prosaic descriptions of space flight.

On January 14, 1966 Korolev was in the Kremlin Hospital for a supposedly routine intestinal operation. Weakened by years of ill-health and overwork, and by the great damage inflicted during his imprisonment in a Siberian labour camp from 1938 to 1940, his body was far more fragile than the doctors had suspected. Internal bleeding proved difficult to control, and two huge tumours had developed in his abdomen. After a lengthy and fraught operation, Korolev’s heart gave out and he died.

Gagarin was furious that the privileged and well-rewarded doctors had not been able to save his mentor and friend. Sergei Belotserkovsky remembers him raging, ‘How can they treat someone so respected in such a mediocre and irresponsible way!’ In fact, Yuri had always said that he did not trust the Kremlin’s special hospital for the élite. In June 1964 Valentina Tereshkova had been assigned a room there so that she could give birth to her baby (seven months after her marriage to Andrian Nikolayev). Gagarin’s barber friend Igor Khoklov remembers his carefully reasoned distrust. ‘He said, “None of those old bosses in the Politburo are capable of fathering babies any more. The Kremlin hospital delivers maybe one or two a month. We must send Valentina to an ordinary people’s hospital where they deliver babies on a conveyor belt, and have the experience to know what they’re doing.” He had a very good relationship with Tereshkova, by the way.’ Gagarin’s wishes were granted and the Kremlin hospital lost its star female guest. Now, in the bleak and bitter-cold January of 1966, Gagarin was deeply distressed by Korolev’s death, and angry.

Читать дальше