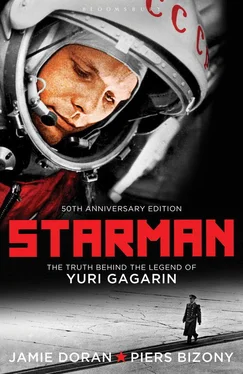

A final decision hinged on NASA literally getting their manned space programme off the ground. On May 5, just twenty-three days after Gagarin had flown, US astronaut Alan Shepard was launched atop a small Redstone booster. His flight was not a full orbit, merely a ballistic ‘hop’ of fifteen minutes’ duration. In contrast to Vostok’s orbital velocity of 25,000 kmph, Shepard’s Mercury achieved only 8,300 kmph. Vostok girdled the globe, while the Mercury splashed down into the Atlantic just 510 kilometres from its launch site. But this cannonball flight was enough to prove NASA’s basic capabilities.

Immediately in the wake of Shepard’s successful flight, Webb made good use of the opportunity to strengthen NASA’s position. His budget advisors within the space agency suggested that he should keep the cost estimates for a moon project as low as possible, if he was to obtain presidential approval, but Webb did not agree. Instead, in one of the most talented administrative bluffs ever attempted by a US civil servant, he doubled the estimates and presented them to Kennedy with an absolutely straight face. It represented a colossal sum of money: upwards of $20 billion in 1960s’ dollars, projected to be spread over the next eight years.

Stunned by the figures involved, Kennedy nevertheless decided to support Apollo. In a historic speech before Congress on May 25, 1961 he said, ‘I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space, and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.’

Meanwhile, Webb and Johnson, canny southern politicians both, began to lay down a subtle and far-reaching network of aerospace contract pledges, construction schemes and political patronage to ensure funding approval for Apollo across forty states. Within four years, NASA’s spending would command 5 per cent of the nation’s entire annual federal budget, and would employ upwards of 250,000 people from coast to coast. Webb called his financial bluff an ‘administrator’s discount’. Modern NASA was built on his belief that the agency had only this one chance to establish itself as a permanent feature of national life, before the momentum for space exploration slackened off. He was quite right. Over the last four decades no other President since Kennedy has been so supportive, nor so willing to spend money on space. [4] Trento, Prescription for Disaster , pp. 48–9.

All this happened because Alan Shepard flew just twenty-three days later than Yuri Gagarin. John Logsdon raises a fascinating conjecture. ‘The flight that Shepard made on May 5 1961, just three weeks after Gagarin, should have happened in March, but a previous Mercury test on January 31 had a chimpanzee called “Ham” on board. The retro-rockets fired late, sending Ham [210 kilometres] downrange of the correct splashdown zone, and it took several hours to recover him – which made for one very unhappy chimpanzee, by the way. The technical problem was very simple, very easy to fix, but they had to do another test of the Mercury before committing a human. So it’s an interesting question: what would have happened if Gagarin had been second? I think history would have worked out very differently.’

But Gagarin was first, and the American reaction was inevitable, particularly given the President’s driven personality. Logsdon says, ‘This wasn’t a Soviet success, but an American failure. I don’t think it was just a question of Kennedy’s responding to public opinion [about Gagarin]. I think he had his own very personal reaction. He always had a very strong need to be first. He was a very competitive person… Perhaps he was looking for an opportunity to show leadership and take some kind of bold action.’

Hugo Young, a journalist from the London Times , observed something similar in 1969:

Kennedy’s response disclosed more than anything the sight of a man obsessed with failure. Gagarin’s triumph pitilessly mocked the image of dynamism which he had offered the American people. It had to be avenged almost as much for his sake as for the nation’s. [5] Young, Journey to Tranquillity , pp. 108–9.

Science advisor Jerome Wiesner surrendered to the inevitable, although he still could not see the point of spending such colossal sums on Apollo. He salved his conscience by forcing a promise from Kennedy. ‘I told him the least he could do was never to refer publicly to the moon landing as a scientific enterprise, and he never did so.’ [6] Ibid., p. 113.

The West quickly developed an obsession with the Space Race, much to the bemusement of cosmonaut Gherman Titov and his friends. ‘What kind of race were they talking about? There wasn’t a race, because we Russians were already ahead of the entire planet.’

Nikita Khrushchev and the Politburo did not immediately respond to Kennedy’s speech with their own moon project. Instead, Khrushchev pressured Korolev for short-term rocket ‘spectaculars’, in the hope of demoralizing the American space effort before it became totally unstoppable. In the longer term, the Soviet economy could not hope to match America’s staggering budgets for Apollo. However, as long as he continued to deliver results with Vostok and with his converted R-7 missile, Korolev could count on the Kremlin’s continuing support for space exploration.

For the time being, NASA was also relying on converted weapon launchers rather than custom-made space boosters. On July 21, 1961 astronaut Virgil ‘Gus’ Grissom flew another sub-orbital curve in a Mercury capsule atop a Redstone ballistic missile, reaching an altitude of 190 kilometres. His mission nearly ended in disaster when the small hatchway on the capsule blew off shortly after he splashed down. He clambered out of the waterlogged craft without his helmet, and water poured down his neck ring and into his spacesuit. He tried to signal the approaching rescue helicopters for help and was amazed to see them flying over the capsule, instead of coming directly to his aid. The helicopter pilots thought Grissom was waving, not drowning. Ignoring him completely, they concentrated on trying to hoist the capsule out of the water before it sank, but it was now so heavy with water that it threatened to pull the helicopter down. Eventually Grissom was rescued, while his capsule sank to the bottom of the Atlantic, beyond all hope of recovery. NASA downplayed the fact that their astronaut was almost lost at sea and hailed Grissom’s mission as a near-perfect success.

On August 6, Gherman Titov took off from Baikonur and flew seventeen orbits aboard the second manned Vostok, staying aloft for twenty-four hours and flying the ship manually for a short period. ‘When I was launched, my wife [Tamara] went into the forest to pick some mushrooms. It was a Sunday, and she disappeared on purpose, to get away from all the journalists asking her annoying questions.’ Titov was extremely nauseous during his flight, the heating in the cabin broke down so that he nearly froze, and his retro-pack did not separate cleanly before re-entry, which gave him some cause for concern: ‘Whether you need this, eh?’ His ejection and landing in the Saratov region were also hazardous, as he recalls today. ‘Under my parachute I passed about fifty metres from a railway line, and I thought I was going to hit the train that was passing. Then, about five metres from the ground, a gust of wind turned me around so that I was moving backwards when I hit the ground, and I rolled over three times. The wind was brisk and it caught the parachute again, so I was dragged along the ground. When I opened my helmet, the rim of the faceplate was scooping up soil. You know, the farmers in Saratov had done their ploughing quite well that season, otherwise my landing would have been even harder.’

Читать дальше