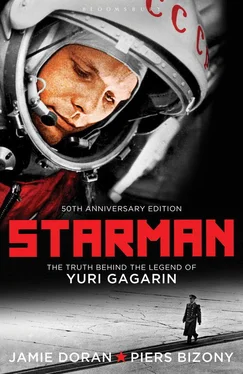

When he grew weary of the adulation at his news conferences, one of Gagarin’s favourite ploys was to remind his listeners that his Hero of the Soviet Union medal was stamped with the number 11,175. ‘That means 11,174 people accomplished something worthwhile before me. I disagree with any division of people into ordinary mortals or celebrities. I’m still an ordinary mortal. I haven’t changed.’ (Once, in Moscow, he laughed happily when he overheard a woman in the crowd say, ‘Oh, look! He’s cut himself shaving.’)

On August 5 Gagarin’s entourage arrived in Canada, at the invitation of the financier Cyrus Eaton. From Halifax they travelled 200 kilometres to Pugwash, Nova Scotia, where Eaton kept a substantial residence. He and the philosopher Bertrand Russell had convened a famous nuclear disarmament seminar known as the ‘Pugwash Conference’ at this house back in 1957. Not surprisingly, Moscow was delighted to receive an invitation for Gagarin to visit, but Eaton’s star guest quickly became distracted. Late on the evening of August 8 he learned that Gherman Titov had gone into orbit. He asked if he could send a congratulatory telegram, and this was arranged for him by Nikolai Kamanin. Titov heard Gagarin’s message during his sixth orbit, relayed to him by ground controllers. Cyrus Eaton politely eased a foreshortening of the festivities so that Gagarin and his colleagues could set off back to Russia immediately. All of a sudden the Russian delegation felt very cut off from important events at home. Kamanin remarked, ‘While we’re busy making speeches, the Americans are preparing spacecraft. We have to move ahead.’

Gagarin’s tour resumed within three weeks. His arrival in Cuba on August 24 was a politically charged event, an important gesture of Soviet solidarity with Fidel Castro’s two-year-old regime. Gagarin and Kamanin stepped off the plane into sweltering heat, dressed in dazzling white summer uniforms. Seen from their end of the political telescope, the Bay of Pigs had been a triumph, not a defeat. Castro’s aides happily told Gagarin, ‘The “beards” repelled the enemy,’ and Gagarin replied, ‘People who believe deeply in the rightfulness of their cause can never be brought to their knees.’ As so often, he knew exactly what to say without prompting. At a mass public rally he declared, ‘All two hundred and twenty million of us Soviet people are the true and devoted friends of Cuba!’ [14] Isvestia , August 28, 1961.

By 1967, the last year of his life, Gagarin would not be so quick to praise the Soviet regime, or to take its every triumphant proclamation so much on trust.

Yuri Gagarin’s short journey through space was one of the most important events of the twentieth century – not for Russia, but for America, where an industrial shake-up of colossal proportions was unleashed in response. It was not just Velcro fabric and the non-stick frying pan that emerged as a result of the Space Race, but the entire fabric of modern technology. Microchips were developed because 1950s’ circuitry was not small enough to fit inside rockets and missiles. The Internet emerged from an attack-proof communications network laid down by ARPA, the Advanced Research Projects Agency (a pre-NASA government department that planned, among other things, for America’s future in space). Modern diagnostic medicine owes an incalculable debt to the research conducted by the space doctors. The development of the global communications industry – for so long a science-fiction dream – happened with incredible speed after the invention of satellites. In all likelihood these technologies would have come along of their own accord, but probably nothing like as fast as they did. And all because a farmboy from Smolensk laid down a challenge to the most powerful nation on earth.

Dr John Logsdon, who heads the Space Policy Institute in Washington, DC, and has advised a succession of Presidents, explains the impact of Gagarin’s flight on the American psyche. ‘It was a sudden rebalancing of our power relationship with the Soviet Union, because of the clear demonstration that – if they wanted to – they could send a nuclear warhead across intercontinental distances, right into the heart of “Fortress America”. There was an uproar: how did we get beaten by this supposedly backward country?’

President Kennedy had not taken space particularly seriously until now, but on the evening of April 14, 1961 he was deeply agitated at the global response to Gagarin’s flight. He paced his office at the White House, asking his advisors, ‘What can we do? How can we catch up?’ Kennedy’s science advisor Jerome Wiesner cautiously suggested a three-month study period to assess the situation, but the President wanted a more urgent response. ‘If somebody can just tell me how to catch up. Let’s find somebody – anybody. I don’t care if it’s the janitor over there, if he knows how.’ He deliberately made these remarks within earshot of Hugh Sidey, a senior journalist from Life magazine. All of a sudden the President wanted to be seen as an advocate for space. [1] Murray & Cox, Apollo: The Race to the Moon , pp. 77–8.

Three days later Kennedy suffered another, more serious defeat. A 1,300-strong force of exiled Cubans, supported by the CIA, landed at the ‘Bay of Pigs’ in Cuba, with the intention of destroying Fidel Castro’s communist regime. Kennedy had personally approved the scheme, but Castro’s troops learned of the operation well ahead of time and were waiting on the beaches. The raid was a total disaster, because the CIA failed to deliver the promised support. Contrary to all expectations, the ‘subjugated’ population of Cuba showed absolutely no desire to participate in Castro’s overthrow. To the CIA’s lasting embarrassment, no attempt was made to rescue the invaders.

The Kennedy administration seemed to be faltering in its first 100 days, the traditional ‘honeymoon’ period during which a new president is supposed to shake things up and make his mark. Kennedy immediately turned to space as a means of reviving his credibility. In a pivotal memo of April 20, he asked Vice-President Lyndon Johnson to prepare a thorough survey of America’s rocket effort: [2] Young, Hugo, Journey to Tranquillity: The History of Man’s Assault on the Moon , London: Jonathan Cape, 1969, p. 110. In addition, Kennedy’s original memo is reproduced as a photograph in the picture section following p. 136.

1. Do we have a chance of beating the Soviets by putting a laboratory in space, or by a trip around the moon, or by a rocket to land on the moon, or by a rocket to go to the moon and back with a man? Is there any other space program which promises dramatic results in which we could win?

2. How much additional would it cost?

3. Are we working 24 hours a day on existing programs, and if not, why not? If not, will you make recommendations to me as to how work can be speeded up.

4. In building large boosters should we put our emphasis on nuclear, chemical or liquid fuel, or a combination of these three?

5. Are we making maximum effort? Are we achieving necessary results?

This single-page document can be read either as one of the most sensational directives of the twentieth century or as a hastily dictated panic response to a bad week at the White House, but without doubt it laid the foundations for the largest technological endeavour since the wartime ‘Manhattan’ development of the atomic bomb: the Apollo lunar landing project.

NASA’s chief administrator James Webb certainly believed that the Soviets could beat America at the short-term goals outlined in Kennedy’s famous memo, such as orbital rendezvous and simple space stations. He suggested a landing on the moon as a longer-range goal, requiring such a tremendous input of resources and technical development that, in all likelihood, the Soviets could not match it. Webb persuaded Kennedy and Johnson to take the longer view, because the short-term battle for rocket supremacy was already lost. [3] See Trento, Prescription for Disaster , pp. 12–13, for a description of Lyndon Johnson’s involvement in the creation of NASA in 1958. See also: Lambright, Henry W., Powering Apollo: James E. Webb of NASA , Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995, pp. 95–6, 132–5;Archives of Dr John Logsdon, Space Policy Institute, George Washington University, Washington, DC, ref: RG 220, NASC files, Box 17, Defence 1961, Webb-McNamara Report, 5-8-1961 .

Читать дальше