Chukovsky: An Introduction

A Guide to Korney Chukovsky Memorial House and Beyond

Tatyana Knyazeva

Cyril Ioutsen

© Tatyana Knyazeva, 2019

© Cyril Ioutsen, 2019

ISBN 978-5-4496-9100-2

Created with Ridero smart publishing system

I was still in primary school when I first came to Korney Chukovsky house – then already a museum – and in those days any encounter with a foreigner, particularly a British or an American, was quite unusual. The same was true during Chukovsky’s time a decade earlier, when each visit from abroad was more or less an exception and had to be minutely coordinated with authorities.

Only in the late 1980s I started to meet foreign guests at the museum, where I had already been helping out. They must have been tourists. I remember how I regretted not to be able to talk without an interpreter, as my school English was insufficient.

It’s a great solace and a pleasure for me to see the younger generation of guides – my colleagues and friends – having written about Korney Chukovsky in English, the language that accompanied him from his youth and was an integral part of his professional life. It was for them a labour of love and respect.

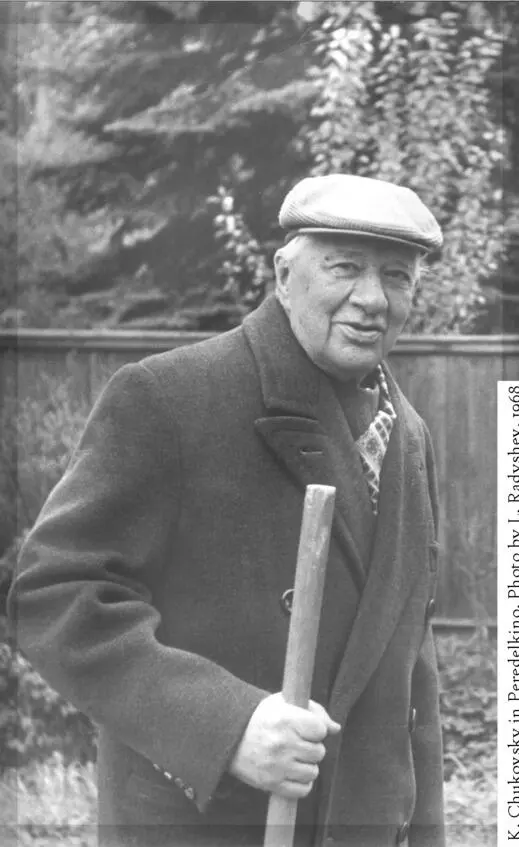

Pavel Kryuchkov, Leading Researcher at the State Museum of the History of Russian Literature, journalist and critic, August 2017

ESTATE. Exterior in winter

Korney Chukovsky (1882—1969) is among the most famous and best-loved people in Russia. For several generations virtually every child in this country has been growing up listening to Chukovsky’s stories, while a lot of his lines and characters have become an integral part of the popular culture. Ironically, however, there are facts, which testify much more vividly to his unique position, and yet are little known.

Chukovsky holds a record as the most published author in Russian language, with a total print run of over 350 million copies, thus closely rivaling Alexander Pushkin (whose head start was a century earlier) and being second only to the Bible. Chukovsky’s career spanned 68 years, his books have been translated into no less than 87 languages, gone through some 2500 different editions and remained continuously in print for more than a century.

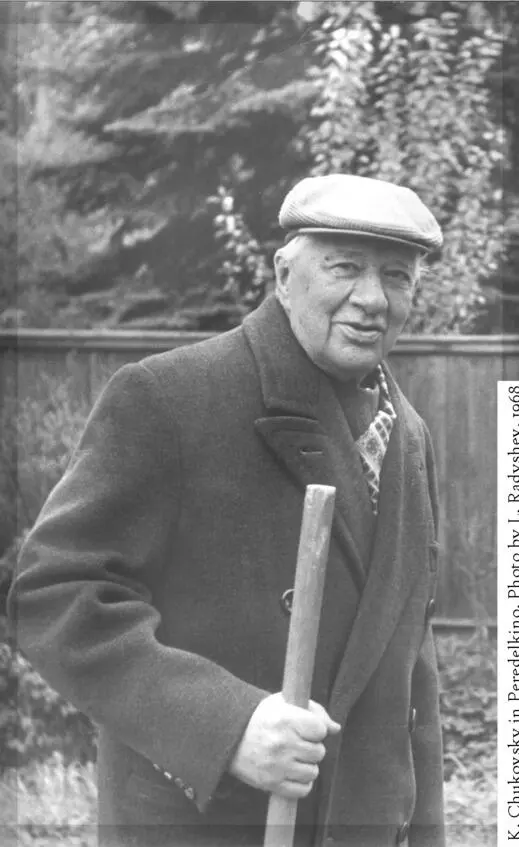

The present introductory work, however concise it may be, is the first original book about Chukovsky written in English and for an English reader. It attempts to cover all the principal directions of Chukovsky’s many endeavours. It is not a biography in a traditional sense and does not pretend to follow a single narrative. Without going into unnecessary details, which might be of limited interest to a non-Russian audience, the book gives a separate broad perspective on each of Chukovsky’s areas of expertise. The illustrations are all exclusive and never before released photographs of his last home – now functioning as Korney Chukovsky Memorial House in the writers’ village of Peredelkino.

This book is published in commemoration of Chukovsky’s 135th anniversary, as well as a centennial jubilee of his first children’s story and 55 years since his acception of Honorary Doctorate at Oxford University.

***

Born in Saint Petersburg, raised in Odessa (then Russian Empire, now Ukraine), Korney Chukovsky came to live in Peredelkino in 1938. The whole village, a brainchild of Joseph Stalin, had been built in a pine forest near Moscow just a few years earlier and was originally meant to accommodate all the best Soviet writers. It has remained a writers’ village ever since, with younger generations coming in and several houses converted into museums.

For almost 25 years, starting with Chukovsky’s death, his house was a cultural pilgrimage destination for tens of thousands of people, and yet – due to authorities’ reluctance – it could not obtain any official memorial status. Lydia Chukovskaya (1907—1996), the writer’s daughter, decided to keep all the furnishings intact and maintained the so called “people’s museum” at her own expense and considerable risk. It was only in 1994 when the house became a subdivision of the State Museum of Literature.

***

In his everyday habits Korney Chukovsky was as modest and hard-working as one surveying his living quarters is led to assume. There are no carefully planned exhibits – only the resident’s last years literally frozen in time, and thus the present-day museum is a creation, even if an inadvertent one, of Chukovsky himself.

The five medium sized rooms contain the whole universe, rich in infinite detail. On the upper floor is the study, the beating heart of the house. Thousands of books, photographs and various memorabilia, along with a massive writing desk packed tight with all sorts of curious objects, demonstrate the breadth and scope of their owner’s numerous activities. Adjacent to the study is the summer terrace with more books and souvenirs. Through the landing, on the other side of the house is the room originally occupied by Chukovsky’s wife, Maria, which he utilized as second study and library after her death in 1955. Here also is a small table with a typewriter – his secretary’s workplace. One wall is solely taken up by photographs paying tribute to one man’s entire life story.

Descending the narrow staircase to the ground floor, with a former kitchen (still keeping its Soviet refrigerator) immediately to the right, and passing Chukovsky’s own cloth-rack on the left, the visitors enter the spacious dining room, a very different-looking domain of the female members of the family. Grand antique furniture of Karelian birch tree, English and German porcelain, crystal chandelier and oil and watercolour portraits used to set the background for many a crowded dinner party. An unremarkable door in a corner leads to the equally humble and sparsely furnished abode of Lydia Chukovkaya – the only room in the house she felt free to have as a dwelling place after her father’s passing.

ESTATE. Bell button at the entrance

For the help and support in the preparation of this book the authors would like to express their gratitude to Dmitry Chukovsky Jr., his father, Dmitry Sr., and sister, Marina, and also Sergey Agapov and all the colleagues at K. Chukovsky Memorial House Department at the State Museum of the History of Russian Literature.

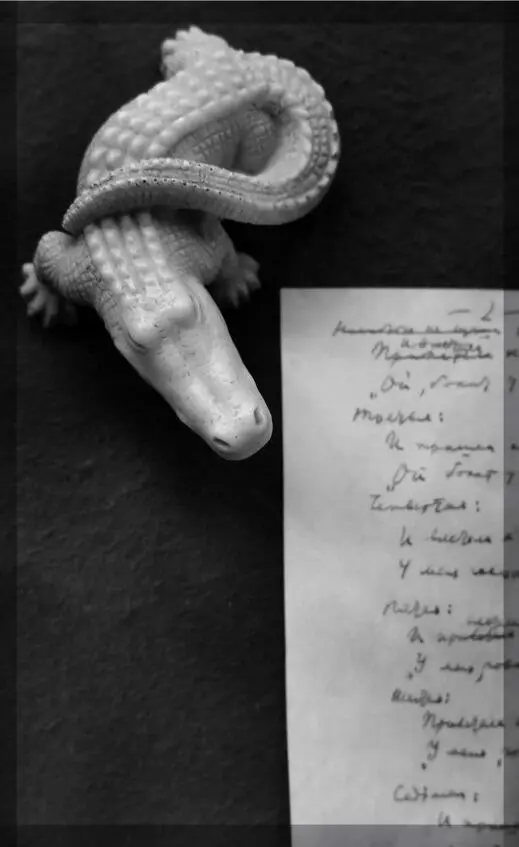

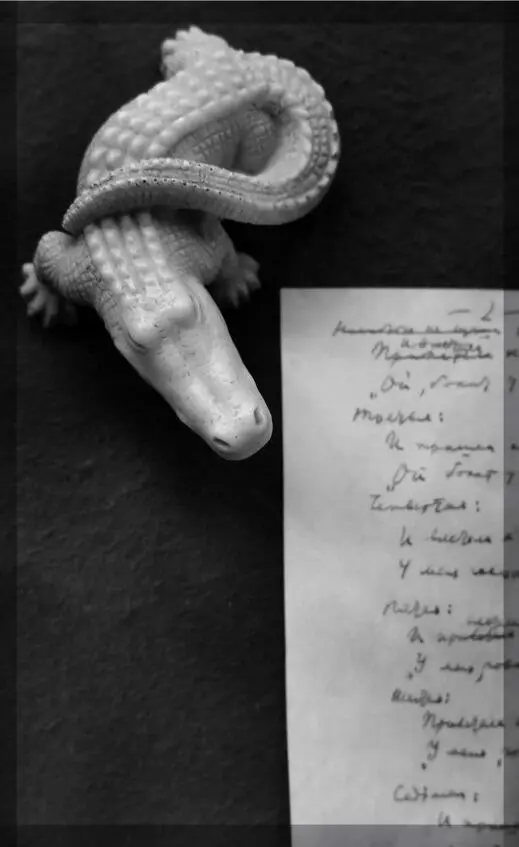

STUDY. Ivory crocodile and a manuscript

The literary debut of a man, born as Nikolay Korneychukov, and later – and much wider – known as Korney Chukovsky, took place in 1901, when his first essay on contemporary art was published in Odessa News. The man who showed him the way to the editorial headquarters was Vladimir Zhabotinsky, the friend of his youth and the future Jewish Revisionist Zionist leader.

Lanky and stooping lad from a penniless and socially disadvantageous background, with barely five years of primary school education, and just come of age, Chukovsky turned out to be quite capable as a columnist, acquiring reputation for reviewing exhibitions, theatre productions and of course books. Apparently he was also the only one on staff who could read English and thus after hardly two years of freelancing for the newspaper was sent to London as an official reporter. During many months of his stay there Chukovsky for the most part spent his time in poor quarters, on a less then modest allowance, observing the city life from the slums and dispatching articles and essays on British people and politics.

Читать дальше